“You have returned.”

“Yes, my lady.” My knees quivered with the strain of kneeling, but I tensed my muscles to show no weakness.

“Where is the child?” Her voice was harsh, and I remembered how she had ordered me from her presence.

“At Ardington, my lady.”

Then Philippa’s hands were stretched to cup my cheeks. “Look at me! Oh, I have longed to see you, Alice!”

My eyes flew to her face, where tears tracked their silvered path.

“My lady…” It shocked me to see such overt grief.

“Forgive me,” she whispered. “I was cruel. I know it—and it was not your fault, but I couldn’t…” Her explanation dried. “You do understand, don’t you?”

“Yes, my lady.”

For of course I did. I kissed her distressingly swollen fingers, rescued the stitchery, and helped her to dry the tears, all as a good domicella should. She had aged in my absence, but still she could manage a watery smile that wrung my heart. And so I slid back into my place in Philippa’s household as easily and smoothly as a trout into a cooking pot of boiling water. Philippa—kindly, suffering Philippa—kissed my cheek, asked after my son, gave me an embroidered robe for the babe, and presented me with a bolt of red silk for a new gown.

In private, Edward enfolded me in his arms and kissed me with Plantagenet fervor. “It has been a long time, Alice.”

“But now I have returned to you.”

“And you won’t leave.”

“Not unless you send me away.”

“I’ll not do that. I’ve been too long without you.”

Too long. I had missed him more than I had thought possible. It was balm to my soul to be kissed and caressed and loved in Edward’s bed.

Isabella left us. Isabella, headstrong and in love, flirted, flounced, cajoled de Coucy, and defied her father in equal measure. De Coucy looked unconvinced at his good fortune in becoming the apple of Isabella’s eye, perhaps wishing he were elsewhere. To wed an English princess was one thing; to take on Isabella and her formidable father was quite another.

“He’s too young, too unimportant,” Edward said, refusing her first request.

“Why can’t you do something useful!” Isabella snarled privately in my direction. “You have the use of much of my father’s body! Surely you have his ear as well! Persuade him, for God’s sake!”

It pleased me to refuse with profound grace, merely to ruffle her royal feathers. “I fear that I am unable to do that, my lady.”

For the King, with or without my interference, would make his own decisions. And he did. Recognizing a lost cause, Edward clamped a tight hold on his true feelings about the match and gave de Coucy the title of Duke of Bedford, made him a knight of the Garter to tie him to English interests, and silently wished the Frenchman well of her. They were wed in the felicitous month of July at Windsor Castle, with all the pomp and splendor that Isabella could persuade her father to pay for. By November they had taken themselves off to France.

“I hope you are no longer here when I next visit,” she said to me before she left. Marriage had not sweetened Isabella’s tongue.

“I wouldn’t wager Edward’s magnificent wedding gift on it!” I could hide my insecurities with great finesse, or even coarse wagering, when I had to.

Isabella managed the ghost of a smile. “Neither would I. A lifetime’s annuity and a king’s ransom in jewels are not to be risked on a certainty. I might even miss your sharp tongue, Alice Perrers.”

Well, well. Was this some manner of a compliment?

“I’ll pray you don’t breed any more bastards,” the Princess added.

No. Her final sally was not friendly, but I might even miss her, I decided as the year slid toward its end. The Court lacked a vibrancy on her departure. For both Philippa and Edward, I gathered my resources to relight the flame.

The year of 1366: It would not be forgotten in a hurry. We had a bad winter, appallingly bad, to bring suffering and worry and grief to the Court as well as to the commons. A hard frost kept us shivering from September to April, curtailing most of Edward’s attempts to set up a hunt, hurling him into an uncharacteristically somber mood. Philippa’s joints ached beyond tolerance, so much so that she kept to her bed. The approach of her death kept her occupied more and more as the days passed. Isabella might have brought some light into her shadowed existence, but Isabella was embracing motherhood in France. Edward was little help to Philippa, wrapped in his own melancholy.

Through those difficult months I tried my best to woo Edward from his moody silences. Would he read? No. Would he have me read to him? No. Play chess or the foolishness of Nine Men’s Morris? Would he take out the hawks on foot along the riverbank, even if it was too dangerous for the horses on the impacted ground? Would he don skates and take exercise on the Thames like the rest of the frustrated and icebound Court?

“Come and play.” I smiled, hoping to engage him in some lighthearted companionship as the sun consented to put in an appearance. “You can leave these documents and give me some of your time.”

“Go away, Alice,” he growled. “I have too much on my trencher to be reading and skating!”

I knew when I was beaten. So I went. I learned to skate and laughed with delight. I was still young and enjoyed the exhilaration.

I lured Edward to his bed on the coldest days, but he was not to be roused. He might kiss me but his manhood refused to be enticed—his mind was far distant from me. I wrapped him in my arms and read to him from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s fine book about the kings of England, selecting the tales of King Arthur—until he closed the book and refused to hear any more about heroes with magic swords. He took himself off to badger Wykeham for news of his latest building schemes. Even that interest was halfhearted.

I could not blame him and bore no grudges. Had I not learned my lesson, that I did not always come first with a man of such grave responsibilities? For the King had reason enough for the blackness that wrapped his soul like a shroud. My heart ached for him. For the Prince, his glorious son and heir, lord of Aquitaine, had persuaded Edward to finance a campaign to reinstate Pedro of Castile, who had been deposed by his subjects. A risky project in the depths of winter, as Edward was well and truly warned by Wykeham—invasion would be a grievous mistake—but, like the King of old, he grasped at the chance to be conqueror once more, forced a war budget through Parliament, raised an army, and handed authority over this invading force to another warlike son, John of Gaunt. He, together with the Prince invading from Aquitaine, would bring a solution to Castile’s inheritance problems and glory to England.

“What do you think, Alice?” Edward asked as I sat at his feet before the fire in his chamber, although I think he did not care what I thought. He sipped gloomily from a cup of ale, and I sought for something to cheer him.

“I think you are the most powerful king in Christendom.”

“Will England be victorious?”

“Of course.”

“Will I still be seen as the man who holds the power in Europe in his fist?”

He raised his hand and clenched it, the tendons proud against the flesh. Age pressed particularly heavily on him that night. In the shadows the pale gold of his hair was entirely eclipsed by dull gray.

“Undoubtedly you will.”

He smiled. “You are good for me, Alice.”

I took the rigid fist, smoothed out the fingers between my own, and kissed them, aware of my ignorance and deficiencies as king’s counselor. What did I know of the state of England’s authority over the sea? Very little, but we were all to learn the truth over the coming weeks.

The King should have listened to Wykeham.

Our invading forces, beset by storms and gales and a shortage of food, were reduced to a fifth of their original size, with no booty or prisoners to compensate. Sitting in his chamber or pacing the halls of Havering, Edward could do nothing to determine events except to rely on his sons to uphold the English cause. Inactivity gnawed at him day and night. Why did he not go himself, to lead as he once had done? Because he too saw the waning of his powers. The future was with his sons, and it hurt him, seeing the end of his glory. However hard I tried through that winter, I could not heal the wounds for him.

As for English affairs in Ireland, they seemed likely to sink to their death into the famous bog. Edward’s son Lionel scrabbled at an impossible settlement, reducing Edward to vicious oaths against his son’s ineptitude.

Philippa despaired and wept.

And I? How did I fare? Did we, Edward and I, emerge from the morass of black despair? Holy Virgin! It was balanced on a knife’s edge, and I could have lost everything, for we faced a crisis that was, I admit, of my own deliberate making.

Frustrated with the cold rooms of Havering, in a fit of pique Edward departed to Eltham at the turn of the year, and at Philippa’s insistence we moved also, the whole Court, to be with Edward.

“You’ll see,” she fretted as her possessions were packed around her, setting her teeth against the prospect of a painful journey in a litter, however luxurious the cushions. “Eltham has more space. He feels hemmed in here. And we must hear good news from Gascony soon. We can’t leave him to brood. It does him no good.”

But, despite the new planned gardens and Edward’s own pride in the newly planted vineyard, Edward brooded in the spacious accommodations at Eltham as effectively as he had at Havering. He roared through the halls and audience chambers, patient with no one except Philippa, insisting on taking out the hounds, hard ground or no, snarling at the grooms when they were slow to deal with icy fingers and frozen leather. He snarled at me too.

“Come with me,” he snapped. “I want you with me!”

He kept me waiting, shivering in the cold outside the stables, while he listened to a report of a courier just ridden in. Only the week before he had given me a mantle of sables, wrapping my naked body in his gift in a moment of brittle good humor. I wore it now, but I might have been wearing the lightest of silk for all the good it did to keep me warm in the bitter wind.

“Let’s go!” he ordered, his temper on as short a leash as the hounds. “What are you waiting for?”

“Her Majesty is not well, my lord. I should be with her.” It was not quite an excuse. The journey to Eltham had stirred her joints to a new level of agony. Sleep for her was a distant memory without a draft of poppy.

“We’ll be back before noon.”

“Jesu! It’s too cold for this,” I murmured.

“Then don’t come. I’ll not force you.” He swung up into the saddle. The courier’s news had not pleased him.

For a moment I considered accepting his surly irritability and leaving him to his ill humor. Then perversely I joined the hunt. I regretted it, of course, returning with damp hems and frozen feet and mud-splattered skirts. My blood felt sluggish in my veins. Nor had the hunt been a success. We put up nothing for the hounds, everything of sense having gone to ground. We were frozen to the bone and Edward in no better mood.

He had spoken not one word to me—other than to “keep up, for God’s sake”—when we galloped after a scent that proved to be as ephemeral as the King’s good temper. Back at the palace, our steaming horses led away to the stables, I trailed after him as Edward stripped off gloves and hood and heavy cloak, thrusting them into my arms as he strode into the Great Hall as if I were his body servant. Without even a glance in my direction, he raised his hand, a royal summons, without courtesy.

Rebellion spiked my blood. Was this all I was to him, a servant to fetch and carry and obey unspoken orders? I halted, my arms full of muddy cloak. It was only when Edward had crossed the antechamber to the staircase leading up to the royal apartments that he realized my footsteps were not following him. He halted, spun ’round. Even at that distance I could see that his jaw was rigid.

“Alice…!”

I moved not one inch.

“What’s wrong with you, girl?”

I considered what I should say. What would be wise? I thought briefly that it might be prudent to say nothing and simply follow. And promptly consigned wisdom to the fires of hell and remained exactly where I was.

“I’m cold. Don’t just stand there.” Edward was already mounting the stairs.

I abandoned prudence too.

“Is that all you can say?” I asked.

Edward froze, his eyes a steely glint. “I want you with me.”

For a moment we were alone in the vast arching chamber. There was no one there to hear us. I raised my voice. I think I would have raised it if we had had an audience of hundreds.

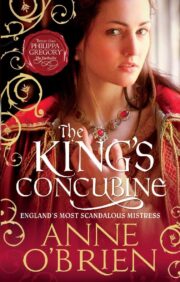

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.