No, I had not known.

“The Prince was not too ill to spend time putting weasel words into the ear of the Abbot. So there it is. March, the de la Mare cousins, and the Prince, all tied into a stratagem to keep me and my heirs from the throne.”

Never had Gaunt spelled out his ambitions so clearly. Not to me. Not, I surmised, to anyone. For it was dangerous talk. Treasonous, in fact, for it all came back to the problem of the future succession. If the Prince’s son Richard died without issue, the son of March and Philippa would rule England through order of descent, for Philippa had carried a son, a lad of three years old now. Not Gaunt. Not Gaunt’s boy, Henry Bolingbroke. Would Gaunt be vicious enough, ambitious enough, to destroy the claim of his nephew Richard, or that of the infant son of March? Watching his fist clench hard against the window ledge, I thought he might. But thought was not proof.…

Whatever the truth of it, rumor said that the Prince lived in fear that his son might never rule if Gaunt had his way. And the Prince from his sickbed was using the allies he had: the de la Mare cousins and now March, who had apparently discovered he had much to gain in opposing Gaunt.

I forced my mind to untie the knots. I still couldn’t quite see where this was leading. Unless the new de la Mare Speaker of the Commons intended to use the one weapon he had to get what he and his coconspirators wanted. My mind began to clear. The one weapon that would give him much power…

“Do you think that the Commons will grant finance for the war…?” I queried.

“At a price. And I wager de la Mare has it all planned to a miracle of exactness. He knows just what he will ask for, by God!”

“What?”

“I scent danger on the wind. They’re planning an attack. On me, on my associates in government. Latimer and Neville. Lyons. The whole ministerial crew, because I helped them into office. De la Mare and March will plot and intrigue to rid Edward of any man who has a connection with me. Gaunt will be isolated; that’s the plan. Brother warring against brother.” Gaunt’s smile was feral, humorless, as his eyes blazed. “And they will declare war on you too, Mistress Perrers, unless I’m way off in my reading of de la Mare’s crafty mind. Any chance that I might step into my brother’s shoes will be buried beneath the crucified reputations of royal ministers and paramour alike.” He folded his arms, leaning back against the stonework. “I did not think March had such ambitions. I was wrong. Being sire to the heir to the throne obviously appeals to him.”

Sire to the heir? But only if Richard were dead…Or perhaps Richard did not need to die.…The complications wound around my brain like a web spun by a particularly energetic spider. March—and even Gaunt—might challenge the boy’s legitimacy because of Joan’s scandalous matrimonial history. They would not be the first to do so, but…I could not think of that yet. There was a far more urgent danger.

“Can you hinder Speaker de la Mare?” I asked.

“What can I do? The Commons are elected and hold the whip hand over finance,” Gaunt responded, as if I were too much a woman to see it. “I’d look a fool if I tried and failed.” When he rubbed his hands over his face, I realized how weary he was. “You have to tell the King.”

My response was immediate and blunt. “No.”

“He needs to know.”

“What would be the point? If you can do nothing, what do you expect from an old man who no longer thinks in terms of plans and negotiations and political battles, who cannot enforce the authority of royal power? You’ve seen him when he is as drained as a pierced wine flask. What could he do? He’d probably invite de la Mare to share a cup of ale and discuss the hunting in the forest hereabouts.”

“He is the King. He must face them and…”

“He can’t. You know he can’t.” I was adamant. I watched as the truth settled on Gaunt’s handsome features, so like his father’s. “It will only bring the King more distress.”

Gaunt flung his ill-used gloves to the floor. For a moment he studied them as if they would give him an answer to the crisis; then he nodded curtly. “You’re right, of course.”

“What will you do?” I asked as he recovered his gloves and walked toward the door, his thoughts obviously far away. My question made him stop, slapping his gloves against his thigh, searching for a way forward.

“I’ll do what I can to draw the poison from the wound. The only good news is that the Prince is too weak to attend the sitting in person. It might give me a freer hand with Speaker de la Mare. If we come out of this without a bloody nose, it will be a miracle. Watch your back, Mistress Perrers.”

“I will. And I will watch Edward’s too.”

“I know.” For a moment the harshness in his voice was dispelled. “I detest having to admit it, but you have always had a care for him.” Then the edge returned. “Let’s hope I can persuade the Prince to have mercy on his father and leave him to enjoy his final days in peace.”

He made to open the door, clapping his hat on his head, drawing on his gloves, and I wondered. No one else would ask him, but I would.

“My lord…”

He came to a halt, irritably, his hand on the door.

“Do you want the crown for yourself?”

“You would ask that of me?”

“Why not? There is no one to overhear. And who would believe anything I might say against you?”

“True.” His lips acquired a sardonic tightness. “Then the answer is no. Have I not sworn to protect the boy? Richard is my brother’s son. I have an affection for him. So, no, I do not seek the crown for myself.”

Gaunt did not look at me. I did not believe him. I did not trust him.

But who else was there for me to look to? There would be no other voice raised in my defense.

Gaunt was gone, leaving me to search out the pertinent threads from his warning. So the Prince was behind the Commons attack, intent on keeping his brother from the throne. Every friend and ally of Gaunt would be dealt with. And I saw my own danger, for I had failed to foster any connection between myself and the Prince. But perhaps I was a fool to castigate myself over an impossible reconciliation. Could I have circumvented Joan’s loathing? I recalled her vicious fury over the herbs, her destruction of the pretty little coffer. No, the Prince would see me as much a whore as his wife did.

Could I do anything now to draw the poison, as Gaunt had so aptly put it? I could think of nothing. Edward was not strong enough to face Parliament and demand their obedience as once he might. He needed the money. And what would the price be for de la Mare’s cooperation to keep the imminent threat of France at bay? Fear was suddenly perched on my shoulder, chattering in my ear like Joan’s damned long-dead monkey.

Watch your back, Mistress Perrers!

I considered writing to Windsor, but abandoned that exercise before it was even begun. What would I say? I could expect no help from that quarter before the ax fell. If it fell. All was so uncertain. I shivered. I would simply have to hope that its sharp edge fell elsewhere.

In those days following Gaunt’s warning, while I sat tight in Westminster and rarely left Edward’s side, the name of Peter de la Mare came to haunt my dreams and bewitch them into nightmares. I gleaned every piece of information that I could. Neither Edward nor the Prince attended any further sessions, so all fell into the lap of Gaunt, who tried to chain de la Mare’s powers by insisting that a mere dozen of the Commons members should present themselves to confer privately with Gaunt in the White Chamber. De la Mare balked at the tone of the summons. How clear was the writing on the wall when he brought with him a force of well over a hundred of the elected members into a full session of Parliament? There they stood at his back, as their Speaker put forward his intent to the lords and bishops in the Painted Chamber.

He called Gaunt’s bluff, and it put the fear of God into me. This was a dangerous game de la Mare was playing, and one without precedent, as he challenged royal power. I would not wager against his victory.

Oh, Windsor. I wish you were here at Westminster to stiffen my spine.

I must stand alone.

Gaunt’s description of events during that Parliament, for my personal perusal, was grim and graphic. Thud! Speaker de la Mare’s fist crashed down against the polished wood. Thud! And thud again, for every one of his demands. Where had the money gone from the last grant? The campaigns of the previous year had been costly failures. There would be no more money until grievances were remedied. He flashed a smile as smooth as new-churned butter. Now, if the King was willing to make concessions…It might be possible to reconsider.…

Oh, de la Mare had been well primed.

There must in future be a Council of Twelve—approved men! Approved by whom, by God? Men of rank and high reputation to discuss with the King all matters of business. There must be no more covens—an interesting choice of word that clawed at my rioting nerves—of ambitious, self-seeking money-grubbers to drag the King into ill-conceived policies against the good of the realm.

And those who were now in positions of authority with the King? What of them?

Corrupt influences, all of them, de la Mare raged, neither loyal nor profitable to the Kingdom. Self-serving bastards to a man! Were they not a flock of vicious vultures, dipping their talons into royal gold to make their own fortunes? They must be removed, stripped of their power and wealth, punished.

And when Parliament—when de la Mare—was satisfied with their dismissal? Why, then the Commons would consider the question of money for the war against France. Then and only then.

“Do they think they are kings or princes of the realm?” Gaunt stormed, impotent. “Where have they got their pride and arrogance? Do they not know how powerful I am?”

“You have no power when Parliament holds the purse strings,” I replied. The knot of fear in my belly grew tighter with every passing day, as we awaited the final outcome.

And there it was.

Latimer, Lyons, and Neville were singled out as friends of Gaunt. And the charge against them? De la Mare and his minions made a good legal job of it, ridiculously so. Not one, not a score, but more than sixty charges of corruption and abuse, usury and extortion. Of lining their pockets from trade and royal funds, falsification of records, embezzlement, and so on. I had a copy of the charges delivered to me, and read them with growing anxiety. De la Mare was out for blood; he would not be satisfied with anything less than complete destruction.

I tore the sheet in half as the motive behind the charges became as clear as a silver coin dropped into a dish of water. Guilt was not an issue here. The issue was their tight nucleus of control, a strong command over who had access to the King and who had not. Latimer and I might see our efforts as protection of an increasingly debilitated monarch; de la Mare saw us as a blight that must be exorcised by fire and blood. What did it matter that Latimer was the hero of the nation, who had excelled on the field of Crécy? What did it matter that he ran Edward’s household with superb efficiency? Latimer and his associates were creatures of Gaunt. De la Mare was delirious with power and would have his way. Gaunt was helpless.

Throughout the whole of this vicious attack on his ministers, Edward was ignorant.

For what was I doing?

Trying to keep the disaster from disturbing Edward, whose fragility of mind increased daily. And I would have managed it too, having sworn all around him to secrecy, except for a damned busybody of a chamber knight, a friend of Latimer and Lyons, who begged for Edward’s intercession.

I cursed him for it, but the damage was done.

After that there was no keeping secrets.

“They’ll not do it, Edward,” I assured him.

Dismissal. Imprisonment. Even execution for Latimer and Neville had been proposed.

“How can we tell?” Edward clawed at his robe, tearing at the fur so that it parted beneath his frenzied fingers. If he had been able to stride about the chamber, he would have done so. If he had been strong enough to travel to Westminster, he would have been there, facing de la Mare. Instead, tears at his own weakness made tracks down his face.

“This attack is not against you!” I tried. “They will not harm you. You are the King. They are loyal to you.”

“Then why do they refuse me money? They will bring me to my knees.” He would not be soothed.

“Gaunt has it in hand.” I tried to persuade him to take a sip of ale, but he pushed my hand away.

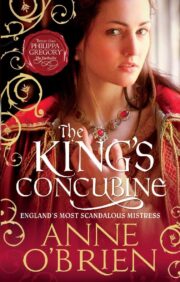

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.