Even his name on my lips was a soft pleasure. All my intentions scattered in the face of his dismissal, and I stepped into his arms as they closed around me.

“That’s better,” he said after a moment when he almost resisted the intimacy. “It almost makes it worth my while returning.”

For a moment we stood silent and unmoving, savoring the shifting patterns of light and shade, my forehead pressed against his shoulder, his cheek resting on my hair, the doll still clutched in my hand. I felt him relax, slowly, gradually, beneath my hands. The robin trilled above us, but we let the deeper silence enfold us.

“So what’s the King doing?” Windsor asked eventually when the robin flew away.

“He’s not doing anything. He’s old and lonely. I don’t think he understands.” I placed my fingers against his mouth when he opened it to deliver, I supposed, some sharp comment on the King, who had accepted my banishment without redress. “He deserves your compassion, Will. Did he not plead for me? And Edward needs me—he is helpless. Who will know how to care for him?” And tears began to slide down my cheek into the damask of his tunic.

“I’ve never seen you weep before! For sure you’ve never wept over me! I think you had better tell me all about it.” Windsor led me to a grassy bank set back near the perimeter hedge and dried my tears with the edge of my cotehardie. He took the doll from me, sitting her down between us as a quaint chaperone, and held my hands between his, his eyes narrowed on my face as I sniffed. “I see you, Alice—before you even think to hide the truth. You’re too thin. When did you last sleep through the night? Your eyes are so very tired.” When he ran the edge of his thumb under my eye, it took my breath away, and then his mouth was warm against my temple. “What terrors have you had to face on your own, my brave girl?”

His compassion all but undermined my self-control. “I am not brave. I’ve been terrified out of my wits.”

“Why didn’t you send for me?”

“What could you have done?”

“Perhaps nothing. Except be here to make sure that you eat and sleep and don’t malinger. You’ve always stood on your own feet, haven’t you?”

“There is no one else.”

“I see.” As his brows snapped together, I thought I had hurt him. But what could he have done at so great a distance? “I’m here now, but you fought your enemies alone. I admire you for it. So tell me what terrified you.” His earlier sharpness crept back. “Unless you prefer to keep it all to yourself.”

Yes, I had hurt him. But that was the life we led.

“I will tell you.”

And I did, with a strange relief, even though I had determined not to. I told him of Parliament’s vendetta. The accusation of necromancy and Joan’s probable involvement. My ultimate banishment. Edward’s brave defense of me at the last, when his heart was split in two.

I sighed. “It’s been quite a month,” I finished.

“So Edward knows about our marriage. And blames you.”

I nodded and sniffed again. “Yes. But he blames you more.” I would tell him the truth. What harm would it do? “Edward damns you for the whole. He blames me for the hurt I caused him, but in his eyes you were the instigator. He thinks you have corrupted me. He even purchased a chest to lock away all the accusations made against you for his future reference. He sits and looks at it and plots his revenge, so I’m told.” I touched his hand. “I don’t think it can ever happen. He no longer has the will to carry it out.”

“Perhaps not, but I am relieved of my position,” Windsor responded, a bright spurt of anger erupting again. “For fraud. What is fraud? A mark on a line of necessity. I have taxed them heavily. I have made my own fortune. But I have kept the peace and the government is at least efficient. I have kept those arrogant lords on a short rein. And all I get is dismissal.” He shrugged and I saw the fire die in his eyes, to be replaced by resignation. “It’s out of my hands. A man who wields authority must always risk losing it.”

“And a woman who has power, unless born to it, makes enemies.”

“So both our names are to be trampled in the mud.” He dried my tears again with his own dusty sleeve—I think I no longer cared if he left smears on my cheeks—and kissed me, a demanding assault on my lips, a little rough, as if he had missed me.

Windsor raised his head and looked at me, his dark eyes holding mine, his thoughts beyond my imagining.

“Don’t weep, my resourceful wife. We shall come about. Is there anything for a much-traveled man to eat and drink in this pearl of a manor?”

Mentally I shook myself into the reality of my orchard at Wendover and the practicality of a long-absent husband returned to me. This was no time for dreams. “There is,” I said. “I’ve been an unthinking hostess.”

“And hot water to remove the filth of travel, perhaps?”

“I could arrange that.”

“Even to remove the odd louse? By God, I’ve stayed in some miserable inns.…”

“Definitely, I can arrange that!”

“And perhaps a bed?”

“I expect so.”

I led him into the house, some semblance of good humor restored between us. After he’d eaten and washed, we banished our concerns to some distant place beyond our bedchamber door and made of our reunion a private celebration. I had forgotten how resourceful he was. His hands and mouth woke my body to a depth of desire that consumed me. Even the worries that had stalked me vanished. How could they exist when he was intent on possessing my body, and I was equally intent on allowing it?

Next morning Windsor was up at dawn. I awoke more slowly, my mind full of spending the day with him and renewing the tentative bonds that we had first created so long ago. But I saw that his sword was gone from where he had dropped it beside the door, and I could hear the sound of the house astir and busy between kitchen and parlor. I dressed rapidly, knowing what I would find before I entered. Windsor, dressed for riding, was already breaking his fast. On the coffer by the door was a leather wallet topped by his gloves, sword, and serviceable hood.

All my bright anticipation fell to earth with a crash. I should have known, should I not? The pleasures of the bedchamber would not keep Windsor from what must be faced and challenged. For a little while I stood on the threshold, studying the stern lines of his face, the quick movement of his fingers, strong and capable, as he sliced and ate, my mind reliving the recent dark hours when he had ignited a flame in me. Then I stepped in.

“Are you abandoning me, Will?” I asked, producing a bright smile despite the chasm that his imminent departure had opened up before me.

“Yes, but not for long. I’ll look at my estates. In spite of an excellent steward, the mice will have been playing while the cat’s away in Ireland, and you, I think, have been preoccupied,” he said around a mouthful of home-cured ham. “But I’ll return by the end of the week.”

I would not have wagered on it, but it had to satisfy me. I came to sit across from him, resting my elbows on the board, taking a sip from his mug of ale. “Will you find out what’s happening at Court for me?”

“If it pleases you. What’s Gaunt doing? Do we know?” Windsor stood, snatching the small beer back again and finishing it, brushing any trace of crumbs from his tunic.

“I don’t know. But he’ll not be content. Parliament humiliated him.”

“Hmm! So he’ll be looking around for opportunities for revenge.” He smiled thinly, as if on a new thought, his hands busy tucking documents into the wallet. “Life might become interesting. I might even become acceptable again.”

I followed him out, deciding to allow him his enigmatic statement. I doubted he would explain, even if I asked.

“Will you try to get news of Edward? Wykeham is a good correspondent, but…”

“I will. He might wish me to Hades, but I’ll do it. God keep you, Alice.” He strapped the wallet to the saddle, whilst I stood like a good wife to wish him Godspeed. Then he turned and surprised me by cupping my face in his hands.

“I’ll do what I can. Don’t fret. I can’t have your sharp wit and intelligence wasting away to a shadow. What would I have to come home to?”

“An amenable wife?”

“God preserve me from such!” A kiss and he was gone. Less than twenty-four hours after he had arrived, with not one word of affection. Or love.

I raised my hand in farewell, retreating smartly into the house as if I did not care. Oh, but I did, and when Windsor did not return within the week I mourned his loss beyond all sense, as if it were a death.

During his absence, Windsor did not forget me or my need for news, sending a courier with a hastily written note. I read it again and again, finding it a lifeline to Windsor, as well as to Edward and the Court. Gaunt, magnificently vocal and brimful of revenge, had declared war on the actions of the Good Parliament.

You will be interested to see how busy he has been in your absence from Court.

And I was, reveling in the details, admiring Gaunt’s ruthless efficiency. He announced that the Good Parliament had proceeded contrary to Edward’s commands, thus rendering its actions null and void. Edward’s new body of twelve councilors was summarily dismissed.

Poor Wykeham was once more deprived of royal office. As was the Earl of March. Gaunt would relish that dismissal, holding the young man wholly accountable for the clever plot with the de la Mares to undermine Gaunt’s own power.

Latimer is released from his imprisonment. I know this will please you.

And then Gaunt began hunting in earnest, his own forces taking Peter de la Mare prisoner.

He is held fast in a cell in Gaunt’s castle at Nottingham. Word is that there is no prospect of a trial. The Earl of March has been forced to hand over his Marshal’s staff in the face of Gaunt’s threats. Gaunt is nothing if not thorough. Try not to be too overjoyed. It is unseemly in Lady de Windsor.

I laughed aloud. I had no sympathy for the man who had forced Edward to plead for me in public. Ah! But I did not enjoy the next paragraph. I think Windsor must have known I would find it hard, because it was written plainly, without comment.

Gaunt has charged Wykeham with fraud as Edward’s Chancellor. I am told that the evidence was thin, but Wykeham is deprived of all his temporal appointments and forbidden to come within twenty miles of Edward’s person. He has retired to a monastery at Merton.…

I regretted it. Once again Wykeham had suffered political isolation for his loyalty to Edward.

And the one name omitted in Windsor’s comprehensive summary?

Alice Perrers. What of me?

Well into the third week, at the end of a sultry day that weighed us down with damp heat so that even taking a breath was wearying, Windsor returned. I was out of the house, dashing into the courtyard, the instant I heard the approach of a horse. I hardly allowed him to swing down from the saddle before I was at his shoulder, pulling on his sleeve.

“What’s happening?”

“Good evening, my wife!”

“What about me?”

“Ah! No one is mentioning your name, my love!”

“Is that good or bad?”

“Impossible to tell.”

“And Edward?”

He shook his head. “He’s ill. It’s thought to be only a matter of time.…”

He looked tired, on the edge of a short temper, as if he had ridden long and hard. As if business had not gone entirely as he would have liked. I sighed. “Forgive me, Will. What of you? I’ve been selfish.…”

“Let us say single-minded.”

Tossing his reins to a groom, he walked with me into the house. He drew my hand companionably through his arm.

“You sent me no word of your fate,” I accused as we moved into rooms dim with evening light.

“What’s to write?”

I saw the glint of anger in his eye despite the shadows. I had been selfish. After a lifetime of major and minor selfishness, I was learning that there were others who needed my compassion and comfort. Windsor seemed an unlikely man to need them—and he would never ask them of me—yet I was beginning to know he might actually value a solicitous welcome from me. So I applied myself to the wifely skills that still came unhandily to me with Windsor, relieving him of his gloves, hood, and mantle, dispatching a servant to bring ale, and pushing him to sit on a settle beneath an ancient oak tree at one side of the house, where we would enjoy the blessing of any movement of air. Conscious of how weary he was, I sat beside him, and leaned to push wayward strands of hair back from his brow where they had stuck with perspiration.

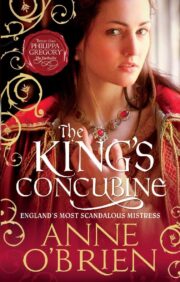

"The King’s Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.