“I think I’ll go to London myself,” I say to her. “And I will write to you as soon as I have news.”

“Please do, Lady Mother,” she says stiffly. “I am always glad to know that you are in good health.”

She comes down with me to the stable yard and stands by my horse as I wearily climb from mounting block to the pillion saddle behind my Master of Horse. In the stable yard my companions mount their horses: my two granddaughters, Jane’s girls, Katherine and Winifred. Harry will stay home with his mother, though he is fidgeting from one foot to another, trying to catch my eye, hoping that I will take him with me. I smile down at her pale face. “Don’t be frightened, Jane,” I say. “We’ve got through worse than this.”

“Have we?”

I think of the history of my family, of the defeats and battles, the betrayals and executions which stain our history and serve as fingerposts to our ceaseless march on and off the throne of England. “Oh yes,” I say. “Much worse.”

L’ERBER, LONDON, SUMMER 1538

“Geoffrey’s in the Tower,” he says quietly the moment that I am seated, as if he feared I would fall at the news. He takes my hand and looks into my stunned face. “Try to be calm, Lady Mother. He’s not accused of anything, there is nothing that they can put against him. This is how Cromwell works, remember. He frightens people into rash words.”

I feel as if I am choking, I put my hand to my heart and I can feel the hammering of my pulse under my fingers like a drum. I snatch at a breath and find that I cannot breathe. Montague’s worried face looking into mine becomes blurred as my eyesight grows dim, I even think for a moment that I am dying of fear.

Then there is a gust of warm air on my face, and I am breathing again, and Montague says: “Say nothing, Lady Mother, until you have your breath, for here are Katherine and Winifred that I called to help you when you were taken faint.”

He holds my hand and pinches my fingertip so that I say nothing but smile at my granddaughters and say: “Oh, I am quite well now. I must have overeaten at dinner for I had such a gripping pain. It serves me right for taking so much of the pudding.”

“Are you sure that you are well?” Katherine says, looking from me to her father. “You’re very pale?”

“I’m quite well now,” I say. “Would you bring me a little wine and Montague can mull it for me, and I shall be well in a moment.”

They bustle off to fetch it, while Montague closes the window, and the sounds of evening on a London street are cut off. I straighten a shawl around my shoulders and thank them as they come back with the wine and curtsey and go.

We say nothing while Montague plunges the heated rod into the silver jug and it seethes and the scent of the hot wine and spices fills the little room. He hands me a cup and pours his own, and pulls up a stool to sit at my feet, as if he were a boy again, in the boyhood that he never had.

“I am sorry,” I say. “Behaving like a fool.”

“I was shocked myself. Are you all right now?”

“Yes. You can tell me. You can tell me what is happening.”

“When we got here, we asked to see Cromwell, and he put us off for days. In the end I met him as if by accident, and told him that there were rumors about us, contrary to our good name, and that I would be glad to know that Gervase Tyndale had his tongue slit as a warning to others. He didn’t say yes and he didn’t say no, but he asked me to bring Geoffrey to his house.”

Montague leans forward and pushes the logs of the fire with the toe of his riding boot. “You know what the Cromwell house is like,” he says. “Apprentices everywhere, clerks everywhere, you can’t tell who is who, and Cromwell walking through the middle of it all as if he is a lodger.”

“I’ve never been to his home,” I say disdainfully. “We’re not on dining terms.”

“Well, no,” Montague says with a smile. “But at any rate, it is a busy, friendly, interesting place, and the people waiting to see him would make your eyes stand out of your head! Everyone of every sort and condition, all of them with business for him or reports for him, or spying for him—who knows?”

“And you and Geoffrey saw him?”

“He talked with us and then he asked us to dine with him, and we stayed and ate a good dinner. Then he had to go and he asked Geoffrey to come back the next day, as there were some few things he wanted to clear up.”

I feel my chest become tight again, and I tap the base of my throat, as if to remind my heart to keep beating. “And Geoffrey went?”

“I told him to go. I told him to be completely frank. Cromwell had read the message that Holland took to Reginald. He knew it wasn’t about the price of wheat in Berkshire last summer. He knew we warned him that Francis Bryan had been sent to capture him. He accused Geoffrey of disloyalty.”

“But not treason?”

“No, not treason. It’s not treason to tell a man, your own brother, that someone is coming to kill him.”

“And Geoffrey confessed?”

Montague sighs. “He denied it to start with, but then it was obvious that Holland had told Cromwell both messages. Geoffrey’s message to Reginald, and Reginald’s replies to us.”

“But still they are not treason.” I find I am clinging to this fact.

“No. But obviously he must have tortured Holland to get the messages.”

I swallow, thinking of the round-faced man that came to my house, and the bruise on his cheek when he was hurried past us on the road. “Would Cromwell dare to torture a London merchant?” I ask. “What about his guild? What about his friends? What about the City merchants? Don’t they defend their own?”

“Cromwell must think he’s on to something. And apparently, he does dare, and that’s why, yesterday, he arrested Geoffrey.”

“He won’t . . . he won’t . . .” I find I can’t name my fear.

“No, he won’t torture Geoffrey, he wouldn’t dare touch one of us. The king’s council would not allow it. But Geoffrey is in a panic. I don’t know what he might say.”

“He’d never say anything that would hurt us,” I say. I find I am smiling, even in this danger, at the thought of my son’s loving, faithful heart. “He’d never say anything that would hurt any of us.”

“No, and besides, at the very worst, all we have done is warn a brother that he is in danger. Nobody could blame us for that.”

“What can we do?” I ask. I want to rush to the Tower at once, but my knees are weak, and I can’t even rise.

“We’re not allowed to visit; only his wife can go into the Tower to see him. So I’ve sent for Constance. She’ll be here tomorrow. And after she’s seen him and made sure that he’s not said anything, I’ll go to Cromwell again. I might even speak with the king when he comes back, if I can catch him in a good mood.”

“Does Henry know of this?”

“It’s my hope he knows nothing. It might be that Cromwell has overreached himself and that the king will be furious with him when he finds out. His temper is so unreliable these days that he lashes out at Cromwell as often as he agrees with him. If I can catch him at the right time, if he is feeling loving towards us, and irritated by Cromwell, he might take this as an insult to us, his kinsmen, and knock Cromwell down for it.”

“He is so changeable?”

“Lady Mother, none of us ever knows from dawn to dusk what mood he will be in, nor when or why it will suddenly change.”

I spend the rest of the evening and most of the night on my knees in my chapel, praying to my God for the safety of my son; but I can’t be sure that He is listening. I think of the hundreds, thousands of mothers on their knees in England tonight, praying for the safety of their sons, or for the souls of their sons who have died for less than Geoffrey and Montague have done.

I think of the abbey doors banging open in the moonlight of the English summer night, of the sacred chests and holy goods tumbled onto shining cobbles in darkened squares as Cromwell’s men pull down the shrines and throw out the relics. They say that Thomas Becket’s shrine, which the king himself approached on his knees, has been broken up and the rich offerings and the magnificent jewels have disappeared into Lord Cromwell’s new Court of Augmentations, and the saint’s sacred bones have been lost.

After a little while I sit back on my heels and feel the ache in my back. I cannot bring myself to trouble God; there is too much for Him to put right tonight. I think of Him, old and weary as I am old and weary, feeling as I do, that there is too much to put right and that England, His own special country, has gone all wrong.

L’ERBER, LONDON, AUTUMN 1538

“I’ve never seen him like this before,” she says. “I don’t know what I can do.”

“What is he like?” Montague asks gently.

“Crying,” she says. “Raging round the room. Banging on the door but no one comes. Taking hold of the bars of the window and shaking them as if he thinks he might bring down the walls of the Tower. And then he turned and fell on his knees and wept and said he could not bear it.”

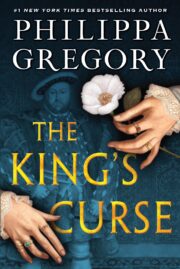

"The King’s Curse" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The King’s Curse". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The King’s Curse" друзьям в соцсетях.