I was speechless with wonder.

“Here is the family crest and look at the family tree; and entwined in the decorations over the fireplace, the initials of the Landowers who were living here at the time it was put in. Can you see anyone else living here … with everything that belongs to us?”

“Oh, Jago, it mustn’t be. I hope it never happens.”

“That is the screens passage over there and the way to the kitchens. I won’t take you there. I daresay the kitchen servants are nodding away, having an afternoon nap. They wouldn’t be very pleased to see us. Come on.” He led me up a flight of stairs to the dining room. Through the windows I could see the lawns and the gardens. Tapestry hung on the walls depicting scenes from the Bible; at either end of the table stood candelabra, and the table was set as though the family were about to sit down for a meal. On the great sideboard were chafing dishes in gleaming silver. This did not seem like a doomed house.

There was a hushed atmosphere in the chapel into which he next led me. It was larger than ours at Tressidor and I felt overawed as our footsteps rang out on the stone flags. Scenes from the Crucifixion were etched on the stone walls; and the stained-glass windows were beautiful, the carvings on the altar so intricate that I felt I should have to spend hours examining them to discover what they implied.

After that he took me to the solarium—a happy room with many windows, and as bright and sunny as its name implied. Between the windows and walls were portraits—Landowers through the ages and some notable people as well.

All about me was antiquity, the evidence of a family who had built a house and had made it a home.

Having seen something of my father’s bitterness over the loss of Tressidor Manor, and Cousin Mary’s pride in it, and determination to keep her hold on it, I understood the tragedy the Landowers were facing.

As I examined the tapestry I was aware that someone had come into the gallery. I turned sharply and saw that it was Paul Landower. I had not seen him since my arrival but I recognized him at once.

“Miss Tressidor,” he said with a bow.

“Oh, good afternoon, Mr. Landower. Your brother is showing me the house.”

“So I perceive.”

“It’s wonderful.” My lips trembled with emotion. “I understand … I couldn’t bear it …”

He said rather coldly I thought: “My brother has been talking of our troubles.”

“Well, why keep it a secret,” said Jago. “You can bet your life everyone knows.”

Paul Landower nodded. “As you say, no point in keeping dark what will be common knowledge soon … very soon.”

“Is there no hope then?” asked Jago.

Paul shook his head. “Not so far. Perhaps we can find a way.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said.

Paul Landower looked at me for a few seconds, then he laughed. “What a way to treat our guest! I’m ashamed of you, Jago. Have you offered her refreshment?”

“I just came in to see the house,” I said.

“Well, I’m sure you would like … tea. Is that so?”

“I’m quite happy just looking at the house.”

“We’re honoured. We don’t often have Tressidors calling.”

“It’s a pity. I am sure anyone would consider it an honour to be invited here.”

“We don’t do a great deal of entertaining now, do we, Jago? It is all we can do to keep the roof over our head and that, my dear Miss Tressidor, let me tell you, is in danger of falling in.”

I looked up in alarm.

“Oh, not immediately. We shall probably get a further warning. We have had little warnings already. What have you shown Miss Tressidor so far?”

Jago explained.

“There’s more to see yet. I’ll tell you what. Bring Miss Tressidor to my ante-room in half an hour. We’ll give her some tea to mark the occasion when a Tressidor comes to Landower.”

Jago said he would do that and Paul left us.

“Things must have gone very badly for him to talk like that,” said Jago. “He’s usually so restrained about our troubles.” He shrugged his shoulders. “Well, no use going over and over something that can’t be helped. Come on.”

There was so much to see. The long gallery with more portraits, the state bedroom which had been occupied by royalty from time to time; the maze of bedrooms, ante-rooms and passages. I looked through the windows across the beautiful park and often into courtyards where I could see the carvings on the opposite walls—often grotesque, gargoyles, threatening intruders, I fancied.

In due course we arrived at the ante-room which I believed led to Paul’s bedroom. It was a small room with a window into a courtyard. There was a small table on which stood a tray containing everything that was necessary for tea.

Paul rose as I entered. “Oh here you are, Miss Tressidor. Have you still a high opinion of Landower?”

I said fervently: “I have never before had the privilege of being in such a wonderful place.”

“You win our approval, Miss Tressidor. Especially as you come from the Manor.”

“The Manor is delightful, but it lacks this splendour … this grandeur.”

“How good you are! How gracious! I wonder if Miss Mary Tressidor would agree with you.”

“I am sure she would. She always says what she means and no one could fail to recognize the … the …”

“Superiority?”

I hesitated. “They are so different.”

“Ah, loyal to Cousin Mary. Well, comparisons are odious, we are told. Suffice it that you admire our house. What a mercy it is you came … just in time.”

I thought: He is obsessed by this tragedy, and I felt very sorry for him, far more than I ever had done for Jago.

He smiled at me and his expression, which before I had thought a little hard, softened. “Now tea will be served. Miss Tressidor, will you do us the honour. It is supposed to be a lady’s task.”

“I’d like to,” I said, and I seated myself at the tea table. I lifted the heavy silver teapot and poured the tea into the very beautiful Sevres cups. “Milk? Sugar?” I asked, feeling very much at ease and grown-up.

Paul did most of the talking. I noticed that Jago was quieter in his brother’s company. Paul asked me about my impressions of Cornwall, about my home in London and the country. I talked vivaciously as I invariably did; but it was different when I spoke of my father. He had always seemed a stranger to me and never more than now. I was surprised how quickly Paul Landower sensed this. He quickly changed the subject.

I was deeply moved by this encounter. I was excited, of course, to be in this ancient house, and at the same time I was sad because of the agony the family was suffering at the prospect of losing it. I felt uplifted in the company of Paul Landower and so pleased that he had come across Jago and me in the house and that he was treating me like a guest.

He was so different from Jago. Jago I looked upon as a mere boy. Paul was a man and a man whose very presence excited me. I liked his virile masculine looks, but perhaps it was that touch of melancholy which stirred me so deeply. I longed to help him. I wanted to earn his gratitude.

I had the impression that he was thinking of me as a rather amusing little girl, and he was interested in me merely because I was a Tressidor, from the rival house. I longed to impress him, to make him remember me after I had gone—as I should remember him.

He talked about the feud between our families in the same way as Cousin Mary had.

“It does not seem much of a feud,” I said. “Here am I a member of one side chatting amicably with members of the other.”

“We could not possibly be an enemy of yours, could we, Jago?” said Paul.

Jago said it was all a lot of nonsense. Nobody thought anything about that sort of thing nowadays. People had too much sense.

“I don’t think it’s a matter of sense,” said Paul. “These things just peter out. It must have been rather fierce in the old days though. Tressidor and Landower fighting for supremacy. We said the Tressidors were upstarts. They said we did not do our duty in the neighbourhood. Probably both of us were right. But now we have the redoubtable Lady Mary who is far too sensible for feuding with enthusiasm. And here are we in a sorry state.”

“I feel you will find a way out of your difficulties,” I said.

“Do you really think so, Miss Tressidor?”

“I’m sure of it.”

He lifted his cup. “I’ll drink to that.”

“I have a feeling,” said Jago, “that no one will buy.”

“Oh … but it’s so wonderful,” I cried.

“It needs a fortune spent on it,” replied Jago. “That’s how I console myself. It has to be someone fabulously rich so that life can be breathed into the tottering old ruin.”

“I still feel that it will come out all right,” I insisted.

When I rose to go I was reluctant to leave them. It had been such an exciting afternoon.

“You must come again,” Paul told me.

“I should love to,” I said eagerly.

Paul took my hand and held it for a long time. Then he looked into my face. “I’m afraid,” he said, “that we have rather overburdened you with our gloomy problems.”

“No, no … Indeed not. I was flattered … to be taken into your confidence.”

“It was really unforgivable. We’re very poor hosts. Next time, we’ll be different.”

“No, no,” I said fervently. “I understand, I do.”

He pressed my hand warmly and I experienced a thrill of pleasure.

He was unlike any person I had ever known and it was his presence, as well as the splendours of the house, which had made this one of the most exciting afternoons I had ever spent.

His looks were outstanding; that strength, tempered with melancholy, appealed to my deep sense of all that was romantic. I wished that I had a great deal of money so that I could buy Landower and hand it back to him.

I was young; I was impressionable; Paul Landower was the most interesting person I had ever met and I was tremendously excited at the prospect of seeing more of him.

Jago said as we rode home: “Paul was unlike himself. He’s usually so restrained. I was surprised he talked so much … in front of you … about the house and all that. Very odd. You must have made some sort of impression, said the right things or something.”

“I only said what I thought.”

“He’s not usually so friendly.”

“Well, I seem to have made a good impression.”

“I believe you and the whole of Cornwall have made a good impression on each other.”

When I reached home I wanted to tell Cousin Mary where I had been. I found her in the sitting room. She looked rather subdued, I thought.

I burst out: “You’ll never guess where I’ve been. Jago took me to Landower to see the house and I met Paul again. He was very friendly and gave me tea.”

I had expected her to be astonished. Instead she just sat staring at me.

Then she said: “I’m afraid I’ve had news from London, Caroline. It’s a letter from your father. You are to go back. Miss Bell is coming next week to take you.”

I was distressed. It was over. I had had such freedom. I had grown to appreciate Cousin Mary. I wanted to go on calling on Jamie McGill, learning more and more about him and his bees and his wicked brother, Donald. Most of all I wanted to become friends with the Landowers.

I was fond of Jago but something had happened since that afternoon with Paul. I had thought about him after the meeting on the train but that encounter in that most fascinating of houses had been a landmark in some way. How could a person one hardly knew loom so important in one’s life?

I wasn’t sure. There was a certain magnetism about him which I had never discovered in any other person. He was not handsome by conventional standards; he looked as though he might be prone to dark moods—but perhaps that was because of the desperate position in which he found himself now. I felt his tragedy deeply; I understood what he must be suffering at the prospect of losing his heritage; and I longed to help. He felt it more than Jago ever could. Jago was by nature lighthearted, perhaps more resilient. I wondered about their father and what he must be suffering at this moment.

Why should I allow their misfortunes to colour my life? I hardly knew them, and yet … I felt so strongly that it must not happen, that some solution must be found.

I had felt great sympathy for Jago, but how much more strongly did I feel for Paul. I was growing up fast. I had begun to do so since that day when I had watched the Jubilee procession from Captain Carmichael’s windows.

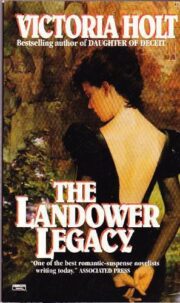

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.