The streets of the city were full of noisy people. I watched them with glee—all those people with their wares who rarely penetrated our part of London; they were there in full force in the city—the chairmender, who sat on the pavement mending cane chairs, the cats-meat man with his barrow full of revolting-looking horseflesh, the tinker, the umbrella mender, and the girl in the big paper bonnet carrying a basket full of paper flowers to be put in fireplaces during the summer months when there were no fires. Then there were the German bands which were beginning to appear frequently in the streets, playing popular songs of the musical halls. But what I chiefly noticed were the sellers of Jubilee fancies—mugs, hats, ornaments. “God Bless the Queen,” these proclaimed. Or “Fifty Glorious Years.”

It was invigorating, and I was glad we had left the country to become part of it.

There was excitement in the house too. Miss Bell said how fortunate we were to be subjects of such a Queen and we should remember the great Jubilee for the rest of our lives.

Rosie Rundall showed us a new dress she had for the occasion. It was white muslin covered in little lavender flowers; and she had a lavender straw hat to go with it.

“There’ll be high jinks,” she said, “and there is going to be as much fun for Rosie Rundall as for Her Gracious Majesty—more, I shouldn’t wonder.”

My mother seemed to have changed since that memorable time when Captain Carmichael had given me the locket. She was pleased to see us, she said. She hugged us and told us we were going to see the Jubilee procession with her. Wasn’t that exciting?

We agreed that it was.

“Shall we see the Queen?” asked Olivia.

“Of course, my dear. What sort of Jubilee would it be without her?”

We were caught up in the excitement.

“Your father,” said Miss Bell, “will have his duties on such a day. He will be at Court, of course?”

“Will he ride with the Queen?” asked Olivia.

I burst out laughing. “Even he is not important enough for that,” I said scornfully.

In the morning when we were at lessons with Miss Bell, my parents came up to the schoolroom. This was so unexpected that we were all dumbfounded—even Miss Bell, who rose to her feet, flushing slightly, murmuring: “Good morning, Sir. Good morning, Madam.”

Olivia and I had risen to our feet too and stood like statues, wondering what this visit meant.

Our father looked as though he were asking himself how such a magnificent person as he was could possibly have sired such offspring. There was a blot on my bodice. I always got carried away when writing and made myself untidy in the process. I felt my head jerk up. I expected I had put on my defiant look, which I invariably did, so Miss Bell said, when I was expecting criticism. I glanced at Olivia. She was pale and clearly nervous.

I felt a little angry. One person had no right to have that effect on others. I promised myself I would not allow him to frighten me.

He said: “Well, are you dumb?”

“Good morning, Papa,” we said in unison. “Good morning, Mama.”

My mother laughed lightly. “I shall take them to see the procession myself.”

He nodded. I think that meant approval.

My mother went on: “Both Clare Ponsonby and Delia Sanson have invited us. The procession will pass their doors and there will be an excellent view from their windows.”

“Indeed yes.” He looked at Miss Bell. Like myself, she was determined not to show how nervous he made her. She was, after all, a vicar’s daughter, and vicar’s families were always so respectable that daughters of such households were readily preferred by employers; she was also a lady of some spirit and she was not going to be cowed before her pupils.

“And what do you think of your pupils, eh, Miss Bell?”

“They are progressing very well,” said Miss Bell.

My mother said, again with that little laugh: “Miss Bell tells me that the girls are clever … in their different ways.”

“H’m.” He looked at Miss Bell quizzically, and it occurred to me that not to show fear was the way to behave in his presence. Most people showed it and then he became more and more godlike. I admired Miss Bell.

“I hope you have thanked God for the Queen’s preservation,” he said, looking at Olivia.

“Oh yes, Papa,” I said fervently.

“We must all be grateful to God for giving us such a lady to rule over us.”

Ah, I thought. She is the Queen, though a woman. Nobody took the crown from her because she was a woman, so Cousin Mary has every right to Tressidor Manor. Thoughts like that always came into my mind at odd moments.

“We are, Papa,” I said, “to have such a great lady to rule over us.”

He glared at Olivia, who looked very frightened. “And what of you? What do you say?”

“Why … yes … yes … Papa,” stammered Olivia.

“We are all very grateful,” said my mother, “and we shall have a wonderful time together at the Ponsonbys’ or Sansons’ … We shall cheer Her Majesty until we are hoarse, shall we not, my dears?”

“I think it would be better if you watched in respectful silence,” said my father.

“But of course, Robert,” said my mother. She went to him and slipped her arm through his. I was amazed at such temerity but he did not seem to mind. In fact he seemed to find the contact rather pleasing.

“Come along,” she said, no doubt seeing how eager we were for the interview to end and growing a little tired of it herself. “The girls will behave beautifully and be a credit to us, won’t you, girls?”

“Oh yes, Mama.”

She smiled at him and his lips turned up at the corners, as though he could not help smiling back although he was trying hard not to.

When the door shut on them we all heaved a sigh of relief.

“Why did he come?” I asked, as usual speaking without thinking.

“Your father feels he should pay a visit to the schoolroom occasionally,” said Miss Bell. “It is a parent’s duty and your father would always do his duty.”

“I’m glad our mother came with him. That made him a little less stern I think.”

Miss Bell was silent.

Then she opened a book. “Let us see what William the Conqueror is doing now. We left him, remember, planning the conquest of these islands.”

And as we read our books I was thinking of my parents, wondering about them. Why did my mother, who loved to laugh, marry my father, who clearly did not? Why could she make him look different merely by slipping her arm through his? Why had she come to the schoolroom to tell us we were going to see the procession, either from the Ponsonbys’ or the Sansons’, when we knew already?

Secrets! Adults had many of them. It would be interesting to know what they really meant, for when they said one thing, they very often meant something else.

I felt the locket against my skin.

Well, I too had my secrets.

As the great day approached the excitement intensified. No one seemed to speak of anything but the Jubilee. The day before there was to be a dinner party and that meant in addition to Jubilee Fever there was the bustle such an occasion always demanded.

In the morning Miss Bell took us for our usual morning walk. The streets near the square, usually so sedate, were filling with traders selling Jubilee favours.

“Buy a mug for the little ladies,” they pleaded. “Come on. Show respec’ for ‘er Gracious Majesty.”

Miss Bell hurried us past and said we would go into the Park.

We walked along by the Serpentine while she told us about the Great Exhibition which had been set up largely under the auspices of the Prince Consort, that much lamented husband of our dear Queen. We had heard it all before and I was much more interested in watching the ducks. We had brought nothing to feed them with. Mrs. Terras, the cook, usually supplied us with stale bread, but on this morning, because of the coming dinner party, she was too busy to be bothered with us.

We sat down by the water, and Miss Bell, always intent on improving our minds, turned the subject to the Queen’s coming to the throne fifty glorious years before, and she went over the oft-repeated tale of our dear Queen’s rising from her bed, wrapped in her dressing gown, her long fair hair loose about her shoulders, to be told she was the Queen.

“We must remember what the dear Queen said—young as she was and wise … oh so wise even then. She said: ‘I will be good.’ There! Who would have believed a young girl could have shown such wisdom? And not much older than you, Olivia. Imagine. Who else could have made such a vow?”

“Olivia would,” I said. “She always wants to be good.”

It occurred to me then that good people were not always wise, and I couldn’t help pointing out that the two qualities did not always go hand in hand.

Miss Bell looked faintly exasperated and said: “You must learn to accept the conclusions of those older and wiser than yourself, Caroline.”

“But if one never questions anything, how can one find new answers?” I asked.

“Why seek a new answer, when you have one already?”

“Because there might be another,” I insisted.

“I think we should now be returning,” said Miss Bell.

How often, I ruminated, were conversations brought to such abrupt terminations.

I did not care. Like everyone else, I was thinking about tomorrow.

From our bedroom we could see the carriages arriving with all the guests and on such a night as this the square seemed full of them. I supposed we were not the only ones who were giving a dinner party.

It was about eight o’clock. We were supposed to be in bed, for we must be fresh for the morning when we would be leaving the house early so that we should be in our places before the streets were closed to traffic. The carriage was to take us to the Ponsonbys’ or the Sansons’— we had not been told which invitation had been accepted. As we were going with our mother, Miss Bell would have to take her chance in the streets and she was accompanying Everton to some vantage point. The servants had made their arrangements. Rosie was going by herself.

“Alone?” I asked and she looked at me and gave me a little push.

“Ask no questions and you’ll hear no lies,” she said.

I think Papa would be at some function. All I cared about was that he should not be with us. He would have cast a decided gloom over the day.

Having seen the carriages arrive, I went with Olivia to our nook by the banisters and watched the guests received.

Our mother was sparkling in a dress trimmed with pink beads and pearls. She wore a little band of diamonds in her hair and looked exquisite. Papa stood beside her, and in his black clothes and frilled shirt he looked magnificent.

We could hear their voices and catch the occasional comment.

“How good of you to come.”

“It is such a pleasure to see you.”

“What a wonderful prelude to the great day.”

And so it went on.

Then my heart leaped with pleasure, for approaching my parents was Captain Carmichael.

So he was back in London as he had said he would be. He looked very handsome, although he was not in uniform. He was as tall as my father and as impressive in his way as my father was in his—only whereas my father cast gloom he brought merriment.

He had passed on and the next guest was received.

I felt bemused. I dared not wear my locket for I was in my night attire and it would be seen. It lay under my pillow. It was safe there, but I should have liked to be wearing it at that moment.

When the guests had all been received I just wanted to sit there.

“I’m going back to bed,” said Olivia.

I nodded and she crept away, but I still sat on, hoping that Captain Carmichael would come out and I should get another glimpse of him.

I listened to the sounds of conversation. Soon they would go down to the dining room which was on the ground floor.

Then my mother came out with Captain Carmichael. They were talking very quietly and soon were joined by a man and woman. The stood for a while talking—about the Jubilee, of course.

I caught scraps of the conversation.

“They say she refused to wear a crown.”

“It’s to be a bonnet.”

“A bonnet! Fancy!”

“Hush! Lese-majesty.”

“But it’s true. Halifax has told her that the people want a gilding for their money and Rosebery says an Empire should be ruled by a sceptre not a bonnet.”

“Will it really be a bonnet? I don’t believe it.”

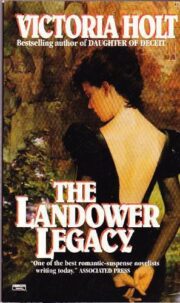

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.