“Let us wait and see,” said the doctor.

So we waited and to my joy after two days Cousin Mary was able to talk a little. She wanted to know what happened. “All I remember is Caesar’s bolting.”

“It was a tree trunk, right across the road.”

“I remember it now. I saw it too late.”

“Don’t talk, Cousin Mary. It tires you.”

But she said: “So we’re here at Landower.”

“I found Paul and he helped me. We’ll be home soon.”

She smiled. “It’s good to have you here, Caroline.”

“I’m going to stay here … right beside you until you’re well.”

She smiled again and closed her eyes.

I felt almost happy that day. She’s going to get better, I said to myself over and over again.

That evening I wrote to Olivia.

“Dear Olivia,

“Something awful has happened. Cousin Mary has had a terrible accident. She was thrown from her horse and has injured herself terribly. I must stay with her. You’ll understand I can’t leave her for some time. That means postponing my visit.

“I am so sorry not to see you but you will understand. Cousin Mary needs me. She is very bad and my being with her comforts her. So … it will have to be later. In the meantime do write to me often. Tell me what you want to by letter. Then I shall be as close as if I were with you.”

I then went on to give her an account of the accident and to tell her that we were staying at Landower and why.

She intruded on my anxieties for Cousin Mary, because the feeling that something was wrong with her would persist.

Cousin Mary improved during the next few days … in spirit, that was. She felt little pain and the doctor told us that probably meant that her spine was injured, but apart from her inability to move she seemed not to have changed very much.

I knew the reverse was the case. She had great spirit and that was evident; but I wondered what effect her condition would in time have on an active woman who had always been independent of everyone— and I shuddered to contemplate that.

In the meantime I was very much aware of the atmosphere which pervaded the house. Living in the midst of it brought it home to me more strongly. It was like a cauldron, murmuring, rumbling, seething, all set to boil over.

As the days passed it became clear to me that my presence did not help. I had no doubt of the strength of Paul’s feelings for me and I was sure that Gwennie was becoming increasingly aware of this. The house seemed to be closing about me, holding me, charming me in a way, claiming me for its own.

I spent a little time with Julian. He looked so delighted when I crept in to his nursery at bedtime. I would read a story to him from the book I had bought him for Christmas and he would avidly watch my lips as they formed the words, sometimes repeating them with me.

There were occasions, too, when I saw him out in the gardens and I would then go and play with him.

Gwennie said: “You and my son seem to be good friends.”

“Oh yes,” I replied. “What a delightful little boy! You must be proud of him.”

“There’s not much Arkwright in him. He looks just like a Landower.”

“I expect there is something of you both in him.”

She grunted. I wondered afresh about her. He was a possession— one would have thought her greatest—but she did not regard him as she did the house. “Pa thought the world of him,” she said.

“Poor Julian! I daresay he misses his grandfather.” I was glad there had been one member of the household who had loved him.

“It’s secured the family line,” said Gwennie. “I don’t think there’s likely to be any more.”

I found this conversation distasteful. I think she knew it and for this reason pursued it. There was a malicious streak in Gwennie. “There had to be some pretence at first, of course,” she said. “That sort of thing’s all over now.”

I said: “You don’t mind my going to see Julian, do you?”

“Why, bless you, no. You go when you like. Make yourself at home. That’s what I say.”

She was looking at me slyly. Did she know that my relationship with Julian was one of bitter-sweetness? Did she know that when I was with him, I thought I might have a child of my own … one rather like this one … dark hair, deep-set eyes, a Landower? Did she understand how I longed for a child of my own?

Gwennie knew a great deal. She was not one of those people—like so many—who are completely absorbed in themselves; she could not resist probing the lives of other people; she liked to discover their secrets, and the more they tried to hide them the more eager was she to know. It was, in a way, the driving force of her life. She knew about my broken love affair, the marriage of my one-time lover with my sister. Such matters were of the utmost interest to her.

I often thought of those servants who watched our actions. Their endeavours were mild compared with those of Gwennie. She was an unusual woman.

Then there was Paul. He was finding it more and more difficult to veil his feelings.

I wondered why he was so indifferent to his son. One day, on a rare occasion when I was alone with him, I asked him. We were in the hall and I had just come in. It was dusk and a blazing fire in the great fireplace threw flickering shadows over the gilded family tree. He said: “Every time I look at him, I think of her.”

“It’s unfair.”

“I know. Life is unfair. I can’t help it. I’m ashamed it ever happened. I don’t want her and I don’t want the child.”

“All you wanted was what she could bring you.” It was the familiar theme. I had harped on it so many times before. I said: “I’m sorry, but it is cruel to a little child who is in no way to blame for what his parents are.”

“You’re right,” he said. “If only you were here … how much happier we should all be.”

He meant if only I were the mistress of this house and mother of his children. It could not be. The house itself prevented that. Time and weather had taken its toll and the house had cried out for the Arkwright fortune—and so the present situation had been created.

“I must go,” I said. “I see that. Soon I must go.”

“It has been wonderful to have you here,” Paul told me. “Even in these circumstances.”

I only repeated that I must go.

I often wondered of how much Cousin Mary was aware as she lay in her bed. She slept for the greater part of the time, but when she was awake I contrived to sit by her bed.

“I shan’t be like this forever,” she said to me.

“No, Cousin Mary,” I replied. But I wondered.

We seemed to be settling into a routine. I walked a little in the gardens. Paul used to watch for me, I believe, for he often came out to join me. We would walk among the flower-beds.

He said: “What is going to be the end of all this?”

“I don’t know. I can’t see into the future.”

“Sometimes we can make the future.”

“What could we do?”

“Find some means …”

“I used to think I should go away … but now I know I must stay with Cousin Mary as long as she needs me.”

“You must never go away from me.”

I said: “There is nothing we can do.”

“There is always a way,” he said.

“If only one could find it.”

“We could find it together.”

Once I thought I saw Gwennie at a window watching us and later that day when I passed through the gallery she was there. She was standing beside one of the pictures. It was a Landower ancestor who bore a resemblance to Paul.

“Interesting, these pictures,” she said. “Fancy them being painted all those years ago. Clever, these painters. They bring out the character. I reckon some of them got up to something in their time.”

I did not answer but gazed at the picture.

A look of cupidity came into her eyes. She said: “I’d like to find out. I reckon there’d be some tales. But most of them are dead and gone … I’d rather know what goes on among the living. I reckon there’d be some revealing, don’t you?”

I said coolly: “I daresay you have some records of what happened in the family.”

“Oh, it’s not the dead ones I’m so interested in.”

There was a gleam in her eyes now. What was she hinting? I had heard that she was insatiably curious about the affairs of her servants. How much more so would she be concerning her own husband!

I must get away from Landower.

Cousin Mary seemed to sense my feeling.

“I want to go back,” she said.

“I know,” I answered. “I’ll speak to the doctor.”

“I’ll speak to him now,” said Cousin Mary.

She did, and as a result he had a conference with Paul and me.

“I think she had better be moved,” said the doctor. “It’s a bit tricky, but she is fretting for her home and I think she should be at peace with herself.”

Paul protested. He wanted us to remain in the house. He insisted that it would be highly dangerous to move her.

The doctor however said: “There is nothing to be done for her. We can at least give her peace of mind. That will be best for her.”

So it was arranged.

They put her on a stretcher which seemed to be the best way of carrying her and they took her back to Tressidor.

Cousin’s Mary’s condition improved a little. She could not move from her bed but she was becoming more like her lively self. Whatever had happened to her body had not impaired her brain.

I was constantly with her. The days were taken up with work and I was glad of this because I did not want time to think of the future. I knew she would never walk again and I wondered what effect that would have eventually even on her spirits. In spite of myself I was getting more and more involved with Paul. He called often to ask after Cousin Mary and he always contrived to be alone with me.

I was glad to see Jago. He supplied the right sort of balm which I needed. He could never be morbid and it was good to be able to laugh now and then.

When I asked him about the machinery he said: “It’s all in the melting pot. But I have my hopes. You’ll hear in due course.”

I didn’t believe him, but before long he was away again, looking mysterious, and even more pleased with himself than he usually was.

Spring had come. Olivia wrote often and I still detected a note of something like wistfulness in what she wrote, and occasionally I fancied I caught a whiff of fear. If I could have left Cousin Mary, I should have gone to her.

April was a lovely month, I always thought—particularly in Lancarron. There was a great deal of rain, showers which would be followed by brilliant sunshine, and I liked to walk in the gardens after the rain had stopped. I rode often and sometimes walked. I went past fields of corn where the speedwells grew a vivid blue and in the lanes where the horse-chestnuts were in flower. Another year had gone. It was nearly six since that Jubilee which had been so fateful for me. I was now twenty. Most young women were married at my age.

It was a thought which must have occurred to Cousin Mary for as I sat by her bed she said: “I should like to see you married, Caroline.”

“Oh, Cousin Mary. I thought you extolled the joys of single blessedness.”

“It can be blessed of course, but it is, I suppose, an alternative.”

“You’re weakening. You really think marriage is the ideal state?”

“I suppose I do.”

“For example, take my mother and your cousin. Think of Paul and Gwennie Landower … and perhaps my sister Olivia and Jeremy. What an ideal state they have worked themselves into!”

“They’re exceptions.”

“Are they? They are the people I know best.”

“It does work sometimes. It would … with sensible people.”

“You think I would be sensible.”

“Yes, I think you would.”

“I’m not sure of that at all. I nearly married Jeremy Brandon, being completely deluded into thinking I was what he wanted. It never occurred to me that I was an investment. What a lucky escape! And that was entirely due to my good fortune rather than any good sense I possessed.”

“You wouldn’t make the same mistake again.”

“People are notoriously foolish in these matters.”

“I wish things could have been different here.”

“What do you mean? You have done so much for me.”

“Nonsense! I’ve had you here because I wanted you to be here. Look at me now … a burden to you.”

“Don’t dare say such a thing! It is ridiculous and quite untrue.”

“Just at the moment perhaps you feel like that. But how long am I going on like this, eh? You don’t know. It could be for years. I don’t want to tie you to an invalid.”

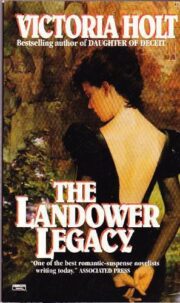

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.