There was one man selling pamphlets. “Fifty Glorious Years,” he called. “Read about the Life of Her Majesty the Queen.” There were two gipsy women, dark-skinned with big brass earrings and red bandanna handkerchiefs tied about their heads. “Read your fortune, ladies. Cross the palm with silver and a fine fortune will be yours.” Then came the clown on stilts—a comical figure who made the children scream with delight as he stumped through the crowds, so tall that he could bring his hat right up to the windows. We dropped coins into it; he grinned and bowed—no mean feat on stilts—and hobbled away.

It was a happy scene—everyone intent on enjoying the day.

“You see,” said Captain Carmichael, “how impossible it would be to get through the streets just yet.”

Then the tragedy occurred.

Two or three horsemen had made a way for themselves through the crowds who good-naturedly allowed them to pass through.

At that moment another rider came into the square. I knew enough about horses to see at once that he was not in control of the animal. The horse paused a fraction of a second, his ear cocked, and I was sure that the masses of people in the square and the noise they were creating alarmed him.

He lifted his front legs and swayed blindly; then he lowered his head and charged into the crowd. There was a shout; someone fell. I saw the rider desperately trying to maintain control before he was thrown into the air. There was a hushed silence and then the screams broke out; the horse had gone mad and was dashing blindly through the crowds.

We stared in horror. Captain Carmichael made for the door, but my mother clung to his arm.

“No! No!” she cried. “No, Jock. It’s unsafe down there.”

“The poor creature has gone wild with terror. He only needs proper handling.”

“No, Jock, no!”

My attention had turned from the square to those two—she was clinging to his arm, begging him not to go down.

When I looked again the horse had fallen. There was chaos. Several people had been hurt. Some were shouting, some were crying; the happy scene had become one of tragedy.

“There is nothing, nothing you can do,” sobbed my mother. “Oh, Jock, please stay with us. I couldn’t bear …”

Olivia, who loved horses as much as I did, was weeping for the poor animal.

Some men had arrived on horseback and there were people with stretchers. I tried not to hear the shot as it rang out. I knew it was the best thing possible for the horse who must have injured himself too badly to recover.

The police had arrived. The streets were cleared. A hush had fallen on us all. What an end to a day of rejoicing.

Captain Carmichael tried to be merry again.

“It’s life,” he said ruefully.

It was late afternoon when the carriage took us home. In the carriage my mother sat between Olivia and me and put an arm around each of us.

“Let’s remember only the nice things,” she said. “It was wonderful, wasn’t it … before …”

We agreed that it had been.

“And you saw the Queen and all the Kings and Princes. You’ll always remember that part, won’t you? Don’t let’s think about the accident, eh? Don’t let’s even talk about it … to anyone.”

We agreed that would be best.

The next day Miss Bell took us for a walk in the Park. Everywhere there were tents for the poor children who were gathered there—thirty thousand of them, and to the strains of military bands each child was presented with a currant bun and a mug of milk. The mugs were a gift to them—Jubilee mugs inscribed to the glory of the great Queen.

“They will remember it forever,” said Miss Bell. “As we all shall.” And she talked about the Kings and Princes and told us a little about the countries from which they came, exercising her talent for turning every event into a lesson.

It was all very interesting and neither Olivia nor I mentioned the accident. I heard some of the servants discussing it.

” ‘ere, d’you know. There was a terrible accident … near Waterloo Place, they say. An ‘orse run wild … ‘undreds was ‘urt, and had to be took to ‘ospital.”

“Horses,” said her companion. “In the streets. Ought not to be allowed.”

“Well, ‘ow’d you get about without ‘em, eh?”

“They shouldn’t be allowed to run wild, that’s what.”

I resisted the temptation to join in and tell them that I had been a spectator. Somewhere at the back of my mind was the knowledge that it would be dangerous to do so.

It was late afternoon. My mother, I think, was preparing for dinner. There were no guests that evening, but even so preparations were always lengthy—guests or no guests. She and my father would dine alone at the big dining table at which I had never sat. Olivia reminded me that when we “came out,” which would be when we were seventeen, we should dine there with our parents. I was rather fond of my food and I could not imagine anything more likely to rob me of my appetite than to be obliged to eat under the eyes of my father. But the prospect was so far in the future that it did not greatly disturb me.

It must have been about seven o’clock. I was on the way to the schoolroom where we had our meals with Miss Bell—we always partook of bread and butter and a glass of milk before retiring—when to my horror I came face to face with my father. I almost ran into him and pulled up sharply as he loomed up before me.

“Oh,” he said. “Caroline.” As though he had to give a little thought to the matter before he could remember my name.

“Good evening, Papa,” I said.

“You seem in a great hurry.”

“Oh no, Papa.”

“You saw the procession yesterday?”

“Oh yes, Papa.”

“What did you think of it?”

“It was wonderful.”

“It is something for you to remember as long as you live.”

“Oh yes, Papa.”

“Tell me,” he said, “what most impressed you … of everything you saw?”

I was nervous as always in his presence and when I was nervous I said the first thing which came into my head. What had impressed me most? The Queen? The Crown Prince of Germany? The Kings of Europe? The bands? The truth was that it was that poor horse which had run amok, and before I had realized it I had blurted out: “It was the mad horse.”

“What?”

“The er—the accident.”

“What accident?”

I bit my lip and hesitated. I was remembering that my mother had implied that it would be better not to talk of it. But I had gone too far to retract.

“The mad horse?” he was repeating. “What accident?”

There was nothing for it but to explain. “It was that horse which ran wild. It hurt a lot of people.”

“But you were nowhere near it. That happened in Waterloo Place.”

I flushed and hung my head.

“So you were in Waterloo Place,” he said. “That was not as I thought.” He went on murmuring: “Waterloo Place. I see … I think I see.” He looked different somehow. His face had turned very pale and his eyes glittered oddly. I should have thought he looked bewildered and a little frightened, but I dismissed the thought; he could never be that.

He turned away and left me standing there.

I went to the schoolroom. I had done something terrible, I knew.

I was beginning to understand. The manner in which we had gone there in the first place when we thought we were going somewhere else … it was significant, the way Captain Carmichael had been expecting us, the looks he and my mother exchanged …

What did it mean? I knew the answer somewhere at the back of my mind. There are things the young know … instinctively.

And I had betrayed them.

I could not speak of it. I drank my milk and nibbled my bread and butter without noticing what I was doing.

“Caroline is absent-minded tonight,” said Miss Bell. “I know. She is thinking of all she saw yesterday.”

How right she was!

I said I had a headache and escaped to my room. Miss Bell usually read with us, each taking turns for a page—for half an hour after supper. She thought it was not good for us to go to bed immediately after taking food, however light.

I thought I would get into bed and pretend to be asleep when Olivia came up, so that I should not have to talk to her. It was no use sharing suspicions with her. She would refuse to consider them—as she always did everything that was not pleasant.

I had taken off my dress and put on my dressing gown. I was about to plait my hair when the door opened and to my dismay Papa came in.

He looked quite unlike himself. He was very angry and he still wore that rather bewildered look. He seemed sad too.

He said: “I want a word with you, Caroline.”

I waited.

“You went to Waterloo Place, did you not?”

I hesitated and he went on: “You need not fear to betray anything. I know. Your mother has told me.”

I was obviously relieved.

He continued: “It was decided on the spur of the moment that you would get a better view from Waterloo Place. I don’t agree with that. You would have been nearer at either of the others which had been offered. But you went to Waterloo Place and were entertained by Captain Carmichael. That’s so, is it not?”

“Yes, Papa.”

“Did you not wonder why the plans had been changed so abruptly?”

“Well, yes … but Mama said it would be better at Waterloo Place.”

“And Captain Carmichael was prepared for you, he provided luncheon.”

“Yes, Papa.”

“I see.”

He was staring at me. “What is that you are wearing round your neck?”

I touched it nervously. “It’s a locket, Papa.”

“A locket! And why are you wearing it?”

“Well, I always wear it, not so that it can be seen.”

“Oh? In secret? And why pray? Tell me.”

“Well … because I like wearing it and … it shouldn’t be seen.”

“Should not be seen? Why not?”

“Miss Bell says I am too young to wear jewellery.”

“So you have decided to defy Miss Bell?”

“Well, not really … but …”

“Please speak the truth, Caroline.”

“Well er—yes.”

“How did you come by the locket?”

I was unprepared for the shock my answer gave him.

“It was a present from Captain Carmichael.”

“He gave it to you yesterday?”

“No. In the country.”

“In the country. When was that?”

“When he called.”

“So he called, did he, when you were in the country?”

He had snapped open the locket and was staring at the picture there. His face had turned very pale and his lips twitched; his eyes were like a snake’s and they were fixed on me.

“So Captain Carmichael made a habit of calling on you when you were in the country.”

“Not on me … on …”

“On your mother?”

“Not a habit. He came once.”

“Oh, he came once, when your mother was there. And how long was his visit?”

“He stayed two nights.”

“I see.” He closed his eyes suddenly as though he could not bear to look at me nor at the locket which he still held in his hand. Then I heard him murmur: “My God.” He looked at me with something like contempt and, still holding the locket, he strode out of the room.

I spent a sleepless night, and I did not want to get up in the morning because I knew there was going to be trouble and that I had, in a way, created it.

There was a quietness in the house—a brooding menace, a herald of disaster to come. I wondered if Olivia sensed it. She gave no sign of doing so. Perhaps it was due to my guilty conscience.

Aunt Imogen called with her husband, Sir Harold Carey, and they were closeted with Papa for a long time. I did not see Mama, but I heard from one of the servants that Everton had said she was confined to her bed with a sick headache.

The day wore on. The brougham did not come to take Papa to the bank. Mama remained in her room; and Aunt Imogen and her husband stayed to luncheon and after.

I was more alert even than usual, for I felt it was imperative for me to know what was going on, and my efforts were rewarded in some measure. I secreted myself in the small room next to the little parlour which led off from the hall and where Papa was with the Careys. It was a cubbyhole really in which was a sink and a tap; flowers were put into pots and arranged by the servants there. I had taken a vase of roses and could pretend to be arranging them if I were caught. I could not hear all the conversation, but I did catch some of it.

It was all rather mysterious. I kept hearing words like scandalous, disgraceful and: “There must be no scandal. Your career, Robert …” and then mumbles.

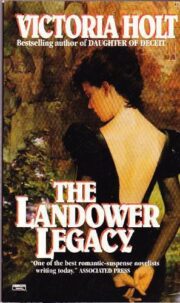

"The Landower Legacy" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Landower Legacy". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Landower Legacy" друзьям в соцсетях.