Renard left his conversation with the Fleming to make a hasty obeisance as the King strode over to him and clapped a powerful arm across his shoulders. Stephen’s enthusiastic proposal filled him with more than a seasoning of doubt.

‘Sire, there is already enough bad blood between us. Whoever wins, it will only increase the enmity,’ he said.

‘Are you refusing me?’ Stephen snapped.

Renard drew a breath and hesitated for a long moment on the peak of it. ‘No, sire,’ he exhaled at last.

‘Leicester’s lad can ride him for you. He’s the lightest boy and he’s got an angel’s touch on the reins. Come on, man, don’t be such a wet trout!’ He shook Renard exuberantly.

Renard could hardly refuse. Besides, it was something he more than half wanted to do. Barring a freak accident, he was as certain of Gorvenal’s victory over the grey as any man could be. The thought made his stomach leap. He also knew that it was folly and if Stephen had the sense to look beneath the surface he would see it too. The problem with Stephen was that he saw his own ungrudging, generous nature in every man he encountered, never realising it was a false reflection.

Against his better judgement, Renard led the horse across the field. Ranulf of Chester gave him a glare which he returned full measure. They had both been at court since yesterday, but thus far separated from each other by the throng of earls and barons in similar attendance on the King. This was their first full meeting since Renard had gone to Antioch. The main enmity stemmed from an incident more than ten years old. De Gernons had been showing off a new and vicious hunting dog. The beast had run amok, Renard had killed it with a jousting lance and there had been trouble. Nothing had changed.

‘Is your grey rested enough, my lord?’ Renard asked his rival with neutral courtesy. ‘I would not want to claim a false victory.’

Ranulf ’s neck started to mottle with angry patches of red that filtered into his stubbled jowls. ‘He’ll leave that pony of yours standing!’ he sneered.

‘Force is not everything, my lord. If you doubt it, go to Ravenstow and look at what remains of a troop of mercen — aries caught raiding on my lands.’ Renard turned to watch Leicester’s boy spring into the saddle.

Chester’s fingers tightened convulsively on the dagger grip. ‘You had no right …’ he started.

‘Neither did they,’ Renard interrupted without turning round, but he was intensely aware of the glare focused on the space between his shoulder blades. He checked the girth for something to do with his hands. ‘It is not in my interests to seek a quarrel with you, but I will bite if provoked.’

Chester dragged on his moustache and narrowed his eyes.

Stephen’s hand came down heavily on the Earl’s thick shoulder. ‘Come now, Ranulf!’ he cajoled. ‘It’s the season of goodwill. Time to abandon old grudges and make peace!’

Chester shuddered beneath Stephen’s encouraging slap, but but he held his body in check.

An interested group of courtiers had gathered around the starting point as the horses were brought round and lined up. De Gernons’s grey stood well over sixteen hands high, the solid power tempered by strains of Barb and Spanish. Gorvenal’s sire had been a desert-bred Bedouin stallion, his dam a mare of Andalusian blood. In consequence he was smaller and lighter than the other horse, but Renard had few qualms. What was lacking in weight was made up in speed.

Each youth fretted his mount back on its hocks, awaiting the King’s signal, and when Stephen dropped his raised arm, both horses sprang forward like shafts from a triggered arbalest.

At first there was no discrepancy. The sheer power of the grey’s initial thrust from the starting line put him a length in front, but as they approached the wooden stake that marked the turning point, it became obvious that the black owned the fleeter turn of foot. The horses swerved neck and neck. The lighter Arab had the advantage of manoeuvre and began to draw ahead as they started the home stretch.

De Gernons’s boy knew the penalty for failure, could already feel the stripes smarting across his back and the boot connecting with his ribs. Fear became panic as the black continued to overtake him, and in desperation he cut his whip at Leicester’s boy.

The youth gave a cry of pain and jerked his arm from the rein to ward off a second blow. Gorvenal’s stride slackened. He wavered, pecked slightly on an uneven piece of ground, and veered into the grey. The whip cut again. The grey’s solid weight barged Gorvenal out of stride and almost brought him down. Chester’s horse regained the lead.

Sobbing with pain and outrage, a bright weal swelling on his white cheek, Leicester’s boy gritted his teeth, dug his heels into Gorvenal’s flanks and drew him wide, asking of the stallion everything he possessed.

Ranulf de Gernons’s premature smile froze. He gaped in utter disbelief as his grey courser, the pride of his stable, was overhauled and taken on the line by a spectacular burst of speed from the black.

Stephen crowed his delight aloud, as tactless but genuine as a small boy. ‘What do you think of FitzGuyon’s pony now!’ he chortled to Earl Ranulf.

‘A fancy toy to be shown off at fairings and the like!’ Chester snarled. ‘That’s no honest mount!’

‘Oh, come now, Ranulf!’ cried Stephen.

‘But then it wasn’t an honest race,’ Renard observed tartly as he went to Gorvenal. ‘Are you all right, lad?’

The boy nodded and gingerly touched the swollen stripe on his cheek. ‘Yes, my lord. He’s got fire in his feet. No side-swipe from a whip was going to stop him!’

Renard gave the boy a silver coin and examined Gorvenal for signs of damage.

Incensed by having lost the wager and Renard’s remark, Chester started forward with a snarl on his lips, but bounced off Leicester’s wide chest. ‘Peace, Ranulf,’ he growled. ‘You’re beaten, you know it, so accept with a good grace for once.’

De Gernons thrust himself out of Leicester’s grip. ‘Don’t lecture at me, Beaumont! You’re not as holy as you think you are!’ Then, glaring at Renard, ‘Enjoy your petty triumph. Hide behind Beaumont and his ilk. I’ll winkle you out of your shell yet on the end of my sword. We have some unfinished business, you and I.’

‘Caermoel is Ravenstow’s,’ Renard said, his voice a calm mask over fear and fury. ‘Copies of the charter are lodged with the monks at Shrewsbury and in Chester itself if you care to look. You’ll not find a single point lacking.’ He turned to Stephen. ‘Perhaps you would like to study the charter yourself, sire, and confirm it?’

Looking at Renard, Stephen was reminded of the old king. Not so strange, for it was in the blood, and the actual bond was closer than his own. He had been delighted when Robert of Leicester had managed to persuade Renard to attend the Christmas court. There had been no open display of rebellion from Ravenstow, but neither had there ever been any tremendous loyalty and Stephen knew that Guyon FitzMiles’s son-in-law, Adam de Lacey, was possessed of strong rebel sympathies. It behoved Stephen to treat this young man generously. The dilemma was how much he could dare to afford.

He vaguely recalled Caermoel being mentioned before. De Gernons disliked the intrusion of the keep within territory he considered his own. It served to prevent the Welsh from raiding, but it was also a watchtower on some of his more questionable activities.

‘Charter?’ Ranulf spluttered furiously. ‘Maurice de Montgomery bribed that land from old King William at the time of the great survey!’

‘Obviously he was setting a precedent.’ The tone of Renard’s retort was caustic.

Ranulf shoved past Robert of Leicester and before anyone could stop him had closed with Renard and seized a handful of his tunic. Renard promptly used the street-fighter’s trick he had shown William in the forest. A slight refinement and an adroit twist of his arm prevented him from being pulled over as his victim toppled like a tree.

‘Enough!’ Stephen roared, horrified, but aware of a treacherous glint of satisfaction, indeed amusement, at the sight of his most powerful tenant-in-chief sprawled thus. Chester opened his mouth to roar out curses and threats. Renard kept his clammed shut, eyes glittering with all that went unsaid. Indeed, some of the anger was self-directed. He knew he should have kept a closer guard on his tongue. It was just that Ranulf of Chester riled him beyond all caution. He had intended Stephen to ratify the Caermoel charter, but quietly, not in a blaze of public display like this, with the main contender howling for blood.

Chester regained his feet. From the way he was standing, it was obvious he had torn a muscle in the fall.

‘There will be peace between you,’ Stephen said, eyes darting between the two men. ‘The matter of the Caermoel charter will be fairly examined and in whomsoever’s favour I find, I will hear no more on the matter. Now give each other the kiss of peace and have done!’

Neither man moved. ‘By Christ!’ Stephen’s complexion was as ruddy as wine. ‘Do as I say. I will have peace between you!’

Chester bestowed a look of contempt on Stephen and, with a shrug that was pure insult, did as he was bid. Renard reciprocated, knowing that their embrace was no overture to piece, but confirmation of a war begun in earnest.

The angry flush on Stephen’s brow and cheekbones, dissipated. He took men at surface value, upon their superficial gestures. ‘Good.’ He gripped Renard’s tense shoulder. ‘Now, about that black of yours. I realise you would not sell him whatever sum I offered, but might I ask the favour of his services at stud?’

Chapter 14

Matilda, Stephen’s queen, bore the same name as her husband’s rival, the Empress, but was affectionately known to close friends and family by her childhood name of Malde. Adored by her husband whom she adored in return, she was definitely the more strong-willed and purposeful of their partnership, and she most certainly did not trust like a child.

This morning, she was holding a court of her own composed of the wives and daughters of the barons who were out with their horses on the tourney field. She looked down at the piece of fabric in her hands and then at the young woman sitting demurely beside her. ‘It is truly a beautiful piece of work, child. Your own, you say?’

‘Yes, madam, woven from our own Woolcot fleeces.’ Elene watched the Queen’s hands smooth the cloth appreciatively. Elene had woven in a border of darker green, cross-banded with thread-of-gold. With the Christmas court in mind, she had set the project in motion the moment she had returned to Woolcot from her marriage feast, and immersed herself in it thoroughly. While she was busy at the dye vats and the loom she did not have the time or inclination to brood upon life’s disappointments.

‘There is enough for two gowns, madam,’ she added, as the Queen gestured and the material was spread out to its full size. ‘Or perhaps tunics for your husband and sons.’

The Queen glanced fondly at a boy who was playing with a bratch hound, tossing a leather ball for it to catch in its mouth. Prince Eustace had his father’s wiry hair and her blue eyes. Prince William, only just two years old, had thrown a tantrum and been removed by his nurse and put in his crib to sleep. ‘Tunics, I think,’ she said. ‘It is thoughtful of you, Lady Elene.’

Elene murmured a disclaimer. It was more than thoughtful, it was calculated. If people knew that King Stephen himself wore cloth of the Woolcot weave they would be more inclined to buy. It was also a personal gift and therefore likely to please the Queen.

Malde gestured to her maids to refold the cloth and cast a sidelong look at Elene. ‘I was sorry to hear of your father-in-law’s continued ill health,’ she said. ‘The King has always regarded him with respect.’

Elene kept her eyes upon her clasped hands while she tried to translate the Queen’s meaning. Whatever Stephen said could be taken at face value. His wife, however, was woven from different fabric entirely. She was Stephen’s backbone, the manipulating force behind his crown. Elene decided that since she was a new bride, wide-eyed and wondering at the complexity of court life and temporarily deserted by her husband, Malde would most likely offer a sympathetic ear and expect confidences in return.

‘It is indeed a great pity, madam’ she agreed sweetly, ‘although he has been a little improved since my husband’s return from Antioch.’

‘I am pleased to hear it, but it is still disappointing that he cannot be here himself and his lady with him.’ She patted Elene’s hand in a maternal gesture that was genuinely meant even if other motives lurked in the background. ‘Nevertheless we are very glad to welcome his heir and new bride.’ Very glad indeed. There had been the distinct possibility that Renard FitzGuyon would spend Christmas at Bristol instead, cementing ties with his uncle, Robert of Gloucester. ‘Your lord has been very busy, we hear, since his return from crusade?’ she added.

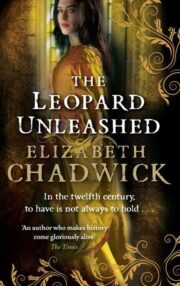

"The Leopard Unleashed" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Leopard Unleashed". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Leopard Unleashed" друзьям в соцсетях.