‘So urgently that you cannot stay to dine?’ She propelled him in the direction of the dais.

‘Oh plenty of time for that, Nell,’ he assured her, patting his stomach, ‘but I won’t stay overnight.’ He gave her a smile. ‘There’s no need to look like that. It’s urgent, but cause for relief, not alarm.’

She raised her brows at him, but did not pursue further. She left him and went down the hall, returning a moment later with Hugh, whom she deposited in his lap. The baby took his usual exception and yelled.

‘He’s definitely louder than I remember from Christmas,’ John said wryly, ‘although even then I marvelled at the power of his lungs.’

‘Renard says that even if you put his cradle in the undercroft, you’d still be able to hear him on the battlements,’ she laughed and poured him wine.

John snorted and put the baby down on the floor to watch him crawl, which he did with concentrated determination. ‘Lord Leicester sends his greetings to you and his godson and hopes to make you a visit soon.’

‘I thought he was with the Empress.’

‘Was,’ John emphasised, taking a swallow of the wine. ‘Only he grew so irritated by her haughtiness and so impressed with Stephen’s fortitude in captivity that he’s returned to the Queen’s party as meek as a washed lamb, and that is only half the good tidings.’

‘Oh?’

‘The Londoners have rejected the Empress too. They let her into the city on midsummer day, reluctantly resigned to giving her the Crown. She needed to handle them as delicately as blown eggshells but instead she demanded money from them — said it was not her fault if they were hard pressed to pay, they should not have squandered their coin on a perjurer like Stephen.’ He shook his head. ‘Both sides left the meeting in high dudgeon. My lady went to eat her dinner; the mob went to fetch their weapons. She escaped by the skin of her teeth. Fled to Winchester so I hear, shedding supporters like autumn leaves.’

‘There is hope then?’ The gold flecks in Elene’s eyes were suddenly very bright.

‘More than there was last month, certainly.’ John’s voice constricted as he leaned from the midriff to rescue his nephew from crawling too far. ‘Apparently the Bishop of Winchester has shut his palace against her and refuses to see her. She won’t give him an inch of ground and it’s beginning to play on his conscience that he betrayed Stephen. After all, they are brothers, and until recently they were very close.’

‘We had heard from William that Winchester petitioned her to let Stephen’s son keep his father’s Norman lands.’

‘It was refused. And then to add insult to injury, she put Stephen in chains. Men are saying that it is disgraceful to treat him thus. My lord of Leicester would have no more to do with her after that. He helped her to escape from the London rabble as a matter of courtesy, but he took the road to Kent, not Winchester.’

‘And Earl Ranulf?’ She took Hugh back from him.

‘Cursing his decision to turn rebel in the first place. Expect him back in the marches full of spleen, but more concerned to defend for the moment than attack.’

Elene looked down at her son, at the chubby hand grasping one of her braid bindings. She felt him heavy and warm in her arms. ‘John, it frightens me,’ she said. ‘I wish there could be peace between us and Chester. I know that Renard fought him off at Caermoel, but it has not stopped the raiding. He sends his routiers to strike at our vulnerable parts and we strike back — ripping out each other’s entrails for the Welsh to feed upon and grow fat.’

‘What does Renard say?’

‘That the blaze is not of his making and that he is not the one who keeps piling on the branches. I suppose it is true, but neither will he make any move towards peace.’

‘You cannot blame him for that,’ John said. ‘Not after what happened to Henry at Lincoln.’

‘I don’t blame him, I just wish there was a way.’

A heavy silence descended. A maid set a bread trencher before John and put a steaming dish of pigeons in saffron sauce upon the table and a savoury accompaniment made of bread, herbs and onions.

Elene sat down with him, giving Hugh a crust to suck, while she picked at her own food.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked John. A servant leaned over him to pour wine into his cup.

‘Nothing … I …’ she hesitated. ‘I … I was thinking that sometimes it is possible for a woman to tread where even angels fear.’

‘You mean go to Earl Ranulf yourself?’ His hand paused, halfway between mouth and trencher and his eyes grew round with alarm. ‘That would be walking into a lion’s den and asking the lion to eat you!’

‘I was thinking of his wife. She is your cousin and not ill disposed towards Ravenstow. I’ve met her before and I think that she would probably agree to help bring this petty warring to a truce.’

John continued to stare at her. After a moment he remembered to put his food in his mouth.

‘Would you carry a letter if I wrote it?’

He swallowed his mouthful convulsively and almost choked. ‘What, behind Renard’s back?’

Elene bit her lip. Then she looked at Hugh and the mess he was making of the crust. ‘Yes.’

‘Are you strong enough to face him when he finds out?’

She thrust her jaw at him. ‘Yes.’

John concentrated on the meal and said nothing until he was washing his hands in the finger bowl. Then he leaned back and folded his arms. ‘A year ago I’d not have believed you, but then a year ago you’d not have answered yes to either question.’

‘A year ago I knew neither Renard nor myself.’

‘And now you do?’

‘I know Renard,’ she said with quiet surety.

John rubbed his chin and noted absently that he needed to shave, knew without feeling that his tonsure would be fuzzy too. ‘Have it written down,’ he said, not at all sure that he was doing the right thing. ‘And I will do my best to deliver it to Matille.’

‘Thank you.’

They looked at each other sombrely, as if their thoughts were made of lead.

To throw off the guilty feeling of conspiracy and ease her mood, Elene had her mare saddled, and when John left, rode with him a little way in order to show him the fulling mill and the weavers’ cottages that now existed in Woolcot village.

John was impressed by the industry and bustling enthusiasm of the operation. Cloth was being cleaned and felted by the pounding of hammers driven by the mill’s water-wheel, and some village women were delivering hanks of distaff-spun yarn to be woven into cloth on the Flemish looms. Another shed housed dye troughs and the frames on which the wet, newly dyed cloth was stretched to dry, secured by tenterhooks. In the final building, Elene showed him a pile of finished bales.

‘This is homespun for the cottars. Some of the women take their wages in cloth.’ She plucked out a corner of a plain, fairly coarse tawny weave, then two smoother ones in green and russet. ‘This is slightly finer, the sort of thing a craftsman or merchant would wear to mass. And for the merchant or wealthier freeman who would like to look as if he wears Flanders cloth but baulks at the price —’ she gestured and Master Pieter, her manager, tugged a dark blue cloth from the foot of the pile. It was fine and soft to the touch with a slightly glossy appearance ‘— Woolcot weave. Half the price of Flemish cloth and twice the quality.’

Mouth open, John stared at her. Then he spluttered and put his palms across his mouth. ‘Elene, you sound like a huckster at a fair!’

‘I’m proud, that’s all,’ she said defensively and blushed poppy-red. Then she looked at him through her lashes and smiled.

‘And rightly so.’ John’s doubts concerning the letter he carried were at one and the same time increased and diminished. Elene’s nature was like amber. It did not give off its glow until it had been warmed, and then heaven help the recipient if he was not prepared.

They returned to their mounts. Guy d’Alberin boosted Elene into the saddle, while John, distracted and thoughtful, set his foot in the stirrup.

‘Have a care to yourself,’ she said. ‘And come back soon.’

‘I will. And I’ll send a message to let you know when I’ve delivered the letter to Cousin Matille.’

She nodded, her smiled apprehensive as she kissed him farewell.

He started up the track that led over the hill and down to the main road. Elene shaded her eyes to watch him and his small escort of serjeants, and resisted the urge to tear after him and take back the letter she had written to the Countess of Chester. For all that she had proclaimed herself capable of standing up to Renard’s wrath, she was nevertheless afraid.

A shout floated on the wind from the direction of the horsemen just gaining the top of the rise and Elene saw them suddenly wheel around and come galloping back down towards her, the foremost man frantically gesticulating. She saw the twinkle of his spurs as he dug them into his horse’s flanks.

Master Pieter came to Elene’s bridle and stared. ‘Trouble afoot,’ he said brusquely. ‘Best go, my lady.’

Elene drew Bramble’s reins through her fingers. On the brow of the slope several more riders appeared. Sun flashed on armour and drawn swords. ‘Holy Mary!’ she whispered and swallowed convulsively. Bile rose in her throat as she remembered her kidnap and the assault that had so nearly ended in rape. Horsemen tearing out of nowhere and ripping the world apart.

Thus far Woolcot had escaped lightly from the Earl of Chester’s raiding. To reach it, his men had to get past the garrison at Caermoel. Twice at least since the siege they had attempted it and twice been beaten. The only other approach was from the east, across Henry’s former lands at Oxley, unoccupied now except for a harassed constable who did his best but was not really fit for the task in hand. Renard had had scant time to give his attention to Oxley, the defence of Caermoel and the earldom being his first priority. It was their Achilles heel and now it was exposed.

‘The church!’ she cried, whirling to Master Pieter. ‘Get everyone into the church!’ It was no guarantee of safety, but it was all they had. ‘I’ll ride back to the castle for aid!’ Turning Bramble, she slapped the reins against the mare’s neck and shrieked in her ear.

Unaccustomed to such rough handling, the little mare broke into a panicky gallop. Elene clung on for dear life, but when Bramble started to slacken pace, she kicked her again and shouted, wishing fervently that she were a man and accoutred with spurs.

Sheep scattered in bleating panic before woman and horse. The ground became tussocky and started to slope. Bramble stumbled and Elene was pitched on to her neck, lost her hold and fell off. The softness of the ground broke her fall, but even so her breath was knocked from her body and she was momentarily too stunned to do anything but lie on the prickly-soft grass, her heartbeat roaring in her ears, blackness before her eyes.

Gradually she became aware of shouting and the clash of weapons as the men of her escort and John’s attempted to hold the routiers while the villagers and cloth workers evacuated to the church. Elene sat up and collected her wits. Apart from bruises, she appeared to be in one piece. She staggered to her feet, hampered by the drag of her skirts. Her legs felt as though they were made of wet hemp. Bramble had stopped several yards away and was looking at her with flickering ears. Not daring to turn around lest she see some of the routiers galloping after her, Elene whistled to the horse and extended her hand. Bramble side-stepped, her nostrils wide, drinking in the smell of smoke.

‘Good girl, Bramble, good girl,’ Elene coaxed, advancing on the mare. Bramble tossed her head and sidled, Elene’s familiar scent warring with the instinct to run from the pungency of the smoke.

Elene closed her fingers round the reins and gasped with relief. Her limbs were weak and trembling but she knew she had to remount. Bramble was trembling too, ready to bolt. Elene set her foot in the stirrup. There was no groom to boost her into the saddle, no mounting block to stand upon, and nothing in sight she could use as one. Bramble was not a large horse, but suddenly she seemed like a mountain.

Sobbing through clenched teeth, Elene struggled. She grabbed a handful of Bramble’s cropped mane, pressed the heels of her hands into the brown, sweating neck and somehow scrambled crabwise across her back. The pommel dug into her abdomen and she had to fight to breathe, but the congestion eased as she came upright and shifted her weight backwards. The mare plunged and circled as Elene searched for the stirrups.

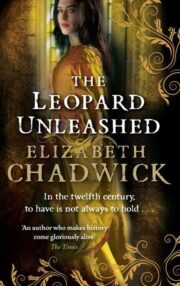

"The Leopard Unleashed" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Leopard Unleashed". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Leopard Unleashed" друзьям в соцсетях.