He said once: "I want to save life, Anabel. I want to make up------"

She said quickly: "You have saved many lives, Joel. You will save many more. You must not brood. It had to be."

I wanted to do something. I wanted to show my love for them and how grateful I was to have been taken away from Crabtree Cottage.

In a way I did have a hand in molding the future and, looking back now, I wonder what might have happened if I had not discovered, through my friendship with these people, what was really going on.

We must have been on the island about six months when the Giant started grumbling.

One of the women heard the rumble when she went to lay a tribute on the lower slopes. It had been an angry rumble. The Giant was not pleased. The rumor spread. I could see the fear in Cougaba's eyes.

"Old Giant grumbling," she said to me. "Old Giant not pleased."

I went to see Wandalo. He was sitting with his stick making very rapid circles in the sand.

"Go away," he said to me. "No time. Giant grumbles. Giant angry. Medicine man not wanted here, says Giant. Want plantation man."

I ran away.

Cougaba was preparing the fish she was going to cook.

She shook her head at me: "Little missy ... big trouble coming. Giant grumbling. Dance of the Masks coming soon."

I gradually learned what was meant by the Dance of the Masks—a little from Cougaba, a little more from Cougabel, and I heard my parents discussing what they had discovered.

For hundreds of years, ever since there had been people on Vulcan, there had been these Dances of the Masks. The custom was practiced on Vulcan Island and nowhere else in the world; and the dance was performed when the grumbling was growing ominous and the shells and flowers did not seem to placate any more.

The holy man—now Wandalo—would take his magic stick and make signs. The god of the mountain would instruct him when the Feast of the Masks should be held. It was always at the time of a new moon because the Giant wanted the rites performed in darkness. When the night was decided, the preparations would begin and go on while the old moon was waning. Masks could be made of anything suitable but they were chiefly of clay and they must completely hide the face of the wearer. Hair was sometimes dyed red with the juice of the dragon tree. Then the feast would be prepared. There were vats of kava and arrack, which was the fermented juice of the palm. There would be fish, turtle, wild pig and fowls, all of which would be cooked on great fires in the clearing where Wandalo had his dwelling. The night would be lighted only by the stars and the fires by which the food was cooked.

Everyone participating in the dance must be under thirty years of age and they must be so completely masked that none knew who they were.

All through the preceding day the drums would be beating, quietly at first... and going on throughout the night. The drum beaters must not slumber. If they did the Giant would be angry. All through the feasting they would continue to beat and, when that was over, the drums, which had been growing louder and louder, would reach a crescendo. That was the signal for the dance to begin.

I did not see the Dance of the Masks until I was much older and I shall never forget the gyrations and contortions of those brown bodies shining with coconut oil, with which they anointed themselves. The erotic movements were calculated to arouse the participants to a frenzy. This was tribute to the god of fertility, who was their god, the Giant of the mountain.

As the dance went on, two by two the couples would disappear into the woods. Some sank where they were, unable to go farther. And that night each of the young women would lie down with a lover, and neither male nor female would know with whom he or she had cohabited that night

It was a simple matter to discover who had conceived, for intercourse between all men and women had been forbidden for a whole moon before. The reason for Cougabel's importance was that she had been conceived on the Night of the Masks.

The belief was that the Grumbling Giant had entered the most worthy of the men and had chosen the woman who was to bear his child; so any woman who had a child nine months from the Night of the Masks was considered to have been blessed by the Grumbling Giant. The Giant was not always lavish with his favors. If not one child was conceived it was a sign that he was angry. There was often no child of that night. Some of the girls were afraid and fear made them barren for, Cougaba told me later, the Giant would not want to bestow his favor on a coward. If there was no child of the night, there would have to be a very special sacrifice.

Cougaba remembered one occasion when a man climbed to the very edge of the crater. He had meant to throw in some shells but the Giant had reached up and caught him. That man was never seen again.

I shall never forget the first Feast of the Masks following our arrival. Everyone was behaving in a very odd way. They averted their eyes when we were near. Cougaba was worried. She kept shaking her head and saying: "Giant angry. Giant very angry."

Cougabel was a little more explicit. "Giant angry with you," she said; and her bright eyes were frightened. She put her arms about me. "No want you die," she said.

I forgot that for a while but one night I awoke remembering it and I thought of the stories I had heard about men being thrown into the crater to pacify the Giant. It was through Cougabel that I realized our danger.

"Giant angry," Cougabel explained. "Mask coming. He will show on Night of Masks."

"You mean he will tell you why he is angry?"

"He is angry because he want no medicine man. Wandalo medicine man. Not white man."

I told my parents.

My father retorted that they were a lot of savages. They should be grateful to him. He had heard that a woman had died of some fever only that day. "If she had come to me instead of going to that old fool of a witch doctor she might be alive today," he said.

"I think you should open up the plantation," my mother put in. "That's what they want."

"Let them do it themselves. I know nothing of coconuts."

The bamboo drums started. They went on all day.

"I don't like them," said my mother. "They sound ominous."

Cougaba went about the house refusing to look at us. Cougabel put her arms round me and burst into tears.

They were warning us, I knew.

We could hear the drums beating; we could see the light from the fires and smell the flesh of the pig. All through the night my parents sat at the window. My father had his gun across his knees. They kept me with them. I dozed and dreamed of frightening masks; then I would wake and listen to the silence, for the drums had stopped beating.

The silence persisted into the next morning.

Later that day a strange thing happened. A woman came to the house in great distress. I had had her pointed out to me as one who had given birth to a child who had been conceived at the last Dance of the Masks. Therefore it was a special child.

The boy was ill. Wandalo had said he would die because the Giant was angry. As a last resort the mother had brought the child to the white medicine man.

My father took the child into the house. A room was prepared for him. He was put to bed and his mother was to stay with him.

Soon the news of what had happened spread and the islanders came to gather about the house.

My father was excited. He said the boy was suffering from marsh fever, and if he had come in time he could save him.

We all knew that our fate hung on that child's life. If he died they would probably kill us—at best drive us from the island.

My father said exultantly to my mother: "He's responding. I might save him. If I do, Anabel, I'll start their plantation. Yes, I will. I know nothing about the business but I'll find out."

We were up all that night. I looked from my window and saw the people sitting there. They had flaming torches. Cougaba said that if the boy died they would set fire to our house.

My father had taken a terrible risk in bringing the boy here. But he was a man to take risks. My mother was such another. So was I, I discovered later.

In the morning the fever had abated. All through the next day the boy's condition improved and by the end of the day it was clear that his life had been saved.

His mother knelt down and kissed my father's feet. He made her get up and take the child away. He gave her some medicine which she gratefully took.

I shall never forget that moment. She came walking out of the house holding the child and there was no need for anyone to ask what the outcome was. It was clear from her face.

People rushed round her. They touched the child wonderingly and they turned to stare in awe at my father.

He raised his hand and spoke to them.

"The boy will get well and strong. I may be able to cure others among you. I want you to come to me when you are sick. I may cure you. I may not. It will depend on how ill you are. I want to help you all. I want to drive the fever away. I am going to start up the plantation again. You will have to work hard for I have much to learn."

There was a deep silence. Then they turned to each other and put their noses together, which I think was a form of congratulation. My father went into the house.

"And to think that was all due to five grains of calomel, the same of a compound of colocynth and of powder of scammony and a few drops of quinine," he said.

No child had been conceived on that Night of the Masks. It was a sign, said the islanders. The Giant had considered them unworthy. He had sent them his friend, the white medicine man, and they had failed to give him honor.

The white man had saved the Giant's child and, because the Giant was pleased at that and because they had performed the Dance of the Masks, he had asked their friend to start up the plantation again.

The island would prosper as long as it continued to pay homage to the Giant.

My father now dominated the island. He became known as Daddajo and my mother was Mamabel. I was known as Little Missy, or the Little White One. We were accepted.

True to his word, my father set about getting the industry of the island working again and because of his immense energy it did not take long. The islanders were wild with happiness. Daddajo was undoubtedly the emissary of the Grumbling Giant and was going to make them rich.

My father immediately started a nursery for coconuts. He had found books on the subject which had been left behind by Luke Carter and they provided him with certain necessary information. He selected a piece of land and placed on it four hundred ripe nuts. The islanders buzzed round in excitement, telling him what to do, but he was going according to the book and when they saw this they were overcome with respect, for he was doing exactly what Luke Carter had done. The nuts were covered with sand, seaweed and soft mud from the beach, one inch thick.

My father had appointed two men to water them daily. They were on no account to neglect to do this, he said, glancing at the mountain.

"No, no, Daddajo," they cried. "No ... no ... we no forget."

"It had better be so." My father was never averse to using the mountain as a threat when he wished to get something done, and it worked admirably now that they were convinced that he was the friend and servant of the Giant.

It was April when the nuts were placed in the square and they must be planted out, said my father, before the September rains came. All watched this operation presided over by my father, chattering together as they did so, nodding their heads and rubbing noses. They were obviously delighted.

The plants were then set in holes two or three feet deep and twenty feet apart and their roots were bedded with soft mud and seaweed. The waterers must continue with their task for two or three years, my father warned, and the new trees must be protected from the glare of a burning sun.

They plaited fronds of palm which they used to shelter the young trees. It would take five or six years before these trees bore fruit, but meanwhile work would progress with those which were already mature and which abounded on the island.

The nursery was a source of delight. It was regarded as an indication that prosperity was coming back to the island. The Grumbling Giant was not displeased with them. Far from sending out his wrath, he had given them Daddajo to take the place of Luke Carter, who had grown old and not caring, so that everyone neglected his or her work and consequently benefits no longer came to the island.

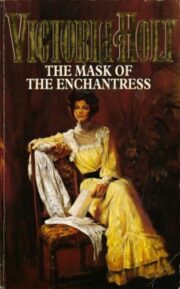

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.