Philip had already heard from me about the Dance of the Masks and how Cougaba had declared Cougabel to be a child of the Giant. He was enormously intrigued by stories of the island and he used to sit with Cougabel and make her talk to him. She was delighted and I felt it had completely set that matter to rights.

"Of course," said my father, "it's that old devil Wandalo who is really making the trouble. He has always resented me. It doesn't matter that we have saved many lives with modern treatment of these virulent fevers which are pests in a climate like this one. I have usurped the place of the old witch doctor and he is longing for a chance to pull down the hospital."

"That's something you will never let him do, I know," said Philip.

"I'll see him dead first," replied my father.

But old Wandalo sat under the banyan tree scrawling on the sand with his old stick, and there were more reports of the Giant's grumbling.

At the next new moon, we heard, there was to be a Dance of the Masks.

Philip and Laura were delighted. That this should have happened during their visit seemed a stroke of good luck to them.

I was more conscious now than I had been before of that mood of frenzy which came over the island. I realized that though my father had introduced so much that was good and which for a time they seemed to appreciate, they could in one night revert to the old savagery. He had never been able to eradicate the fear of the Grumbling Giant and he realized as did my mother that we had been believing he might have done this but it was only because the Giant had been quiet.

Cougabel was in a ferment of excitement. This time she would join the dancers. She prepared herself in secret and my mother said we should have to take special care with a nubile girl in the house. This had not been the case before because at the last dance Cougabel had been very young.

As a daughter of the Giant—which she herself and the islanders believed her to be—this ceremony was of special significance to her. It might well be that the Giant would favor his daughter. "Would that be a matter of incest?" I asked my mother.

"I am sure such a matter would be overlooked in exalted circles such as these," she retorted. Then: "Oh, Suewellyn, we must appear to take this seriously. Old Wandalo is giving your father a great deal of anxiety with these hints."

"Do you really think he could convince them that the Giant doesn't like the hospital?"

"It's Wandalo against your father and I don't doubt that your father will win. But he'll have the weight of centuries of superstition against him."

They were anxious days for us and, while Philip and Laura thought it was all so intriguing, I was deeply conscious of my parents' anxieties.

Cougabel was always beside Philip. She would sit at the door of the house and when he came out run after him. I had seen them sitting under palm trees while she talked to him.

He told me: "I'm collecting all sorts of Vulcan lore. Nothing like getting it from its natural source."

The law had gone out that no husband was to share his hut with his wife for a whole month. Philip was greatly amused, but impressed by the seriousness of the islanders and their determination to bow to tradition. Consequently the women lived together in certain huts and the men in others. Cougaba and her daughter still lived with us and, as we had no male islanders living in, that was considered to be all right.

How the tension mounted during those weeks! My father was impatient. He said there was little work done. They could think of nothing but making their masks.

My mother said: "They'll settle down when it is all past. Your father is disappointed though. He had hoped they were growing out of all this. There are some good men helping him, as you know, and he has been hoping to train them for the hospital, though he first wants a doctor to help him, and he thought he might train some of the women as nurses. But all this makes one doubt he ever will. If they are going to neglect everything for the sake of this ritual dance it shows they are as primitive as ever. Your father is always hoping to explode this foolish Giant legend."

"It will take years to do that," I commented.

"He doesn't think so. He believes that when they see the miracles of modern medicine they will realize that all they have to fear from that mountain is a volcanic eruption ... and the volcano is most likely dead anyway. I think they imagine these grumblings just to stir up a little excitement. By the way, has Philip spoken to you about what your father is suggesting?"

"No," I said a little breathlessly.

"Really! I expect he is waiting until he has thought about it a little longer. But your father was saying that Philip is tempted. He is most interested in the experiment, and your father will need a doctor. Suewellyn, I should be delighted if Philip decided to join us."

I felt myself grow pink with excitement. If he did that I should be so happy.

I did not have to speak. My mother put her arms about me and held me tightly against her. "It would be wonderful," she said. "A solution. It would mean that you would stay here ... you and Philip. You're fond of him. Of course you are. Do you think I can't see it? If he decides to come I am sure it will be something to do with you. Of course he is thrilled by the hospital. He thinks it is such a wonderful idea. He says it's magnificent and he admires your father so much. And isn't it miraculous that he should be as obsessed as your father with the study of tropical diseases?"

"What you are thinking is that Philip and I will marry. He has never suggested it."

"Oh, darling, there is no need for us to be coy. I know he hasn't yet. It's a big step, this... . Probably he wants to talk it over with his parents. He would come out here to live... . Oh, I know we are only a week or so from the mainland but it's a bit of an undertaking. I should be so happy. This hospital ... this industry we have here is the result of your father's work. It's going to be yours one day. Everything your father has has gone into this island. There's nothing left of his properties in England now. We've been living on his fortune for years and now this hospital has taken everything. What I mean is, it is your inheritance ... and what your father and I would like more than anything is to see his successor here before ... before ..."

"You're both going to live for years yet."

"Of course, but it is nice to see things settled. If only we could get rid of that pernicious old Wandalo and his Grumbling Giant and settle down to the real business of living like civilized people, it would be so simple. Now you're embarrassed. You mustn't be. I shouldn't have spoken perhaps but I did want to tell you how happy we should be if ... if it all worked out. Philip is delightful and your father likes him and so do I. And, my dear child, you are fond of him too."

She was right. I was. I could look ahead to a future when we were all here. The island would grow and grow. We would have other amenities here. My father was a man of immense organizing ability. I believe that Philip was not unlike him. They would work well together. Philip was with my father during the hour of the day when he received patients and my father was demonstrating the treatments which were necessary to the diseases indigenous to the islands.

There were at least twelve islands clustered round Vulcan. My father believed that one day they would be a prosperous group. The coconut industry would be developed and they might even set up others. Perhaps then the ship would visit the islands more than once every two months; but his great aim was to discover the source and treatment of island fevers and this he was determined to do.

The beating of the drums had started. Cougabel was shut in her room. I knew that she, like all the girls and men who were to take part in the ritual, was working herself into a frenzy of excitement.

Everywhere we went we could hear the drums. They were quiet... like a whisper during the first hours, but it would not be long before the noise began to swell.

I lay in my bed and thought of Cougabel coming in to tell me she was jealous. I had seen a look in her eyes then which alarmed me. For a second or so I should not have been surprised if she had brought out one of those lanceolate daggers the islanders used and plunged it through my heart. Yes, she had really looked murderous, as though she were planning some revenge for my neglect of her.

Poor Cougabel! When we were children we had scarcely noticed that we were different. We had been the best of friends, blood sisters, and we had been happy together. But it had had to change. I should have been more tender towards her, more considerate. I did not guess that she was so deeply affected by me, but I should have known because she had gone to the mountain-top when I was to go away to school.

The beat of the drums kept us awake all night and we were an uneasy household: my father angry that they should revert to this primitive custom, my mother anxious for his sake and myself faintly worried about Cougabel and at the same time excited by my mother's hints about Philip.

I looked into the future that night and it seemed to me that there was a good possibility of Philip's joining us. It would change everything. And was it really true that he was in love with me and wanted to marry me and share our island life?

It was a pleasant prospect and one which must certainly be shelved for a while. I had another year at school to do yet.

How I wished they would stop beating those drums.

All through the next day they continued. Now we could smell the food cooking in that open space where Wandalo had his dwelling. We were waiting for the dark and the sudden cessation of the drums which was every bit as dramatic as the beating of them.

Silence at last.

It was very dark. I pictured it all, though I had never seen it.

We should stay in the house, my father had always said. He did not know how they would react at seeing a stranger among them and in spite of the fact that we had lived so long among them we were strangers on a night like this.

We tried to go about our normal ways but this was not easy.

Laura came into my room.

"It's so exciting, Suewellyn," she said. "I've never had a holiday like this."

"You have given me some good ones on the property."

"Properties are commonplace," she said. "This is so strange ... so different from anything I have ever seen before. Philip is absolutely wild about the place." She looked at me, smiling. "It has so many attractions. Promise me something, Suewellyn."

"I'd better hear what it is before I answer."

"You'll invite me to your wedding and I'll invite you to mine. No matter what happens, we'll go."

"That's easy," I said.

I spoke lightheartedly. I had little idea how very momentous that promise was going to prove.

"I shan't be going back to school."

"It's going to be deadly without you."

"This time next year it will be your turn to leave."

"What luck it was meeting you! There's only one complaint. You should have been born a year later and then we could both have left school together. Listen."

The silence was over. The drums had started to beat again.

"That means the feasting is over. Now the dance is beginning."

"I wish I could see it."

"No. My father saw it once and so did my mother. It was dangerous. If they had been discovered heaven alone knows what would have happened to them. My father is certain—in fact old Wandalo hinted at it—that they would be very angry. They would discover that the Grumbling Giant was displeased and something dreadful would happen. G.G. would command it-through Wandalo of course." I looked round. "Where is Philip?"

"I don't know. He said he was going to the hospital."

"What for? It's not ready for work yet."

"He just loves to be in the place and plan all sorts of things. Yes, that was where he said he was going."

Fear came to me. Philip was very interested in old customs. Could it be that he had gone to look at the dance? It was dangerous. He didn't realize how dangerous. He had not lived with these people. He had only seen them gentle and eager to please. He did not know the other side of their natures. I wondered what they would do to anyone they found spying at their feast.

"He would never have gone there," said Laura, reading my thoughts.

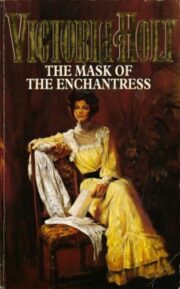

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.