"No, of course," I agreed. "My father did explain that it would be dangerous."

"That wouldn't stop him," said Laura. "But if he thought it would displease your father he would not go."

I was satisfied.

We sat together for some time. We heard the drums reach their crescendo and then there was silence.

This meant that the clearing would be deserted of all but the old people; the young ones would have now disappeared into the woods. The silence created a greater tension than the noise. I went to bed but I could not sleep.

Some instinct made me get out of bed and go to the window. I saw Philip. He was coming from the direction of the hospital; quietly, stealthily he came.

I felt sure he had been watching the dancers. I could understand that he had found it irresistible in spite of my father's warning.

Cougabel awakened me next morning. She was in her native girdle, wearing the shells and amulets about her neck.

She was different. She had been to the feast last night.

Laughing, she came close to me and whispered: 1 know I have the Giant's seed within me. I have Giant's child."

"Well, Cougabel," I said, "for that we must wait to see."

She squatted on the floor and looked at me in my bed. She was smiling and her faraway expression indicated that she was thinking of the night just past.

Cougabel had moved into womanhood. She had had the great experience of the Mask, and she believed, as I suppose all the women did until they knew they were not pregnant, that she carried the Giant's seed within her.

Cougabel was certainly confident. She kept looking at me as though she had scored some triumph.

Later in the day I saw Philip alone and I said to him: "I saw you come in last night."

He looked embarrassed. "Your father warned me," he said.

"But you went," I said.

"I should hate your father to know."

"I shall not tell him."

"It was something I just could not miss. I want to understand these people. And how could one understand them better than on a night like the one just gone?"

I agreed. After all, my father had watched a Night of the Masks. And so had my mother. They had hidden themselves successfully. My father had said: "They are really too absorbed in what they are doing to look for spies."

Philip went on: "I'm coming back, you know."

"Oh, Philip, I'm glad," I answered fervently.

"Oh yes, I've made up my mind. I'm going to work with your father. I have a year to do in the Sydney hospitals first though. By that time, Suewellyn, you'll have done with school."

I nodded happily.

It was tantamount to an agreement.

When I returned to Sydney I missed Laura. I paid a visit to the property. There was a new manager there and he and Laura had become very friendly. I guessed they were in love and when I taxed Laura with it she didn't deny it.

"You'll be dancing at my wedding before I dance at yours," she said. "Don't forget your promise."

I told her I hadn't.

Philip wasn't there. He was doing his year in the hospitals and couldn't get away.

When I went back on holiday to the island it was nearly time for Cougabel's baby to be born. This was a very special birth because it was due nine months after the Night of the Masks and, as until that time, she told me proudly, she had been a virgin, there could be no doubt whose the child was.

"She Mask child and she have Mask child," said Cougaba proudly.

It was typical that Cougaba should go on assuming that we all accepted the fact that Cougabel had been conceived on a night of the dance although she herself had told her that the girl was Luke Carter's daughter. That was a characteristic of the islanders which we found exasperating. They would state something as a fact in face of absolute proof that it was untrue and stubbornly go on believing it.

I had brought a present for the baby, for I was anxious to make up to Cougabel for my neglect in the past. She received me almost regally, accepted the gold chain and pendant which I had bought in Sydney as though, said my irrepressible mother, she was receiving frankincense and myrrh as well as the gold. There was no doubt that Cougabel had become a very important person. She still lived in our house but my mother said we should not keep her, for when the child was born a husband would be found for her and we could be sure that he would be very acceptable. A girl of the Mask, and therefore sure of the Giant's special protection and one who had been born of the Mask herself, as they all believed she had, would be a very worthy wife. And as in addition Cougabel was one of the island's beauties she could expect many offers.

I told Cougabel how glad I was for her.

"I glad too," she said, and made it clear that she was no longer as eager for my company as she had once been.

One night I was disturbed by strange noises and the sound of hurrying footsteps near my room. I put on a robe and went out to investigate. My mother appeared. She took me by the arm and drew me back into the bedroom, shutting the door.

"Cougabel is giving birth," she said.

"So soon?"

"Too soon. The child is a month early."

My mother was looking mysterious and at the same time concerned.

"You see what this means, Suewellyn. It will be said that the child was not conceived on the night."

"Couldn't it be premature?"

"It could be, but you know what these people are. They will say the old Giant would not have let it be born too soon. Oh dear, this could mean trouble. Cougaba is terribly upset. I don't know what we shall do."

"It's all such a lot of nonsense. How is Cougabel?"

"She's all right. Childbearing comes easily to these people who live close to nature."

There was a knock at the door. My mother opened it to disclose Cougaba standing there. She looked at us with great bewildered eyes.

"What's wrong, Cougaba?" asked my mother hastily.

"Come," said Cougaba.

"Is the child all right?" asked my mother.

"Child big, strong, boy child."

"Then Cougabel ..."

Cougaba shook her head.

We went to that room where Cougabel was lying back, triumphant but slightly exhausted. My mother was right. The island women made little trouble of childbearing.

There was the child beside her. His hair was dark brown and straight—quite unlike the thick curly hair of the babies of Vulcan; but it was his skin which was astonishing. It was almost white and that with his straight hair proclaimed the fact that he had white blood in him.

I looked at Cougabel. She was lying there and a strange smile was playing about her lips as her eyes met mine and held them.

There was consternation in the household. First my mother said that none should know that the baby was born. She went at once to tell my father.

"A child that is half white!" he cried. "My God, this is disastrous. And born before the appointed time."

"Of course it could be premature," my mother reminded him.

"They'll never accept that. This could be disastrous for Cougabel ... and us. They will say she was already pregnant before she went to the Mask and you know that's a sin worthy of death in their eyes."

"And the fact that the child is half white ..."

"Cougabel has white blood in her, remember."

"Yes, but ..."

"You can't believe that Philip ... oh no, that's absurd," went on my father. "But who else? Of course Cougabel's father was white and that could account genetically for her giving birth to a child which is even whiter than she is. We know that, but what shall we do about the islanders? One thing is certain. No one outside this house must know that the child is born. Cougaba will have to keep it secret. It is only for a month. Explain to Cougaba. It is necessary, I am sure ... for us all."

And we did that. It was not easy, for the birth of Cougabel's child was awaited with eagerness. Groups of people congregated outside our house. They laid shells round it and many of them went high into the mountain to do homage to the Giant whose child they believed was about to be born.

Cougaba told them that Cougabel needed to rest. The Giant had come to her in a dream and told her that the birth would be difficult. To give birth to his child was not like giving ordinary birth.

Fortunately they accepted this.

My father, always eager to turn disaster into advantage, ordered Cougaba to tell the people that the Giant had come to her in yet another dream and this time he told her that the child would bring a sign for them. He would let them know what he felt about the changes which were coming to the island. In spite of her show of truculence I knew that Cougabel was worried. She understood her people better than we did, and I have no doubt that the premature birth would be as damning in their eyes as the child's color. So both she and Cougaba were ready to follow my father's orders.

The only thing we had to do was keep the birth a secret for a month. In view of the gullibility of the islanders this was not so difficult as it might have been. Cougaba had only to say the Giant had ordered this or that and it was accepted.

But how relieved we were when we could show the baby to the waiting crowd. All our efforts had been worthwhile.

Even Wandalo had to admit that the color of the child indicated that the Giant was pleased by what was happening on the island. He liked the prosperity.

"And most obligingly," said my mother gleefully, "he has stopped that wretched grumbling of his. It couldn't have been more opportune."

So we emerged from this delicate situation. But in spite of my father's assertion that it was not so very rare for a colored person who had had a white father to produce a light-colored child, I kept thinking of Philip and pictures of him and Cougabel laughing together returned again and again to my mind.

I think my feelings toward Philip changed at that time. Or perhaps I was changing. I was growing up.

Susannah on Vulcan Island

Soon after that I went back to school for my last term; and when I came back Philip was installed on the island.

To be with him again reassured me that my suspicions were unfounded. Cougabel had planted those thoughts in my mind and she had done so deliberately. I remember Luke Carter's saying that the islanders were vindictive and never omitted to take revenge. I had made Cougabel jealous and, knowing my feelings for Philip, she was repaying me through him.

Silly girl! I thought. And sillier was I to have allowed myself to believe what I did for a moment.

The baby flourished. The islanders brought him gifts and Cougabel was delighted with him. She took him up to the mountain to give thanks to the Giant. It occurred to me that, whatever else Cougabel was, she was very brave, for she had deceived her people and yet she dared go to the mountain to give thanks to the Giant.

"But perhaps she was thanking him because she was extricated from this difficult predicament," my mother suggested. "But in fact she should be thanking us."

I was very happy during the months that followed. Philip had become like a member of the family. I was finished with school, and my parents were happier than they had ever been before— except for those rare moments which my mother had once mentioned. I realized now that they were at peace. As time passed danger receded and their big anxiety had been on my account.

Now I knew they were thinking that I should marry Philip and settle here for the rest of my life. I should not be confined as they had been. I should be able to take trips to Australia and New Zealand and perhaps go home for a long stay. The islands were prospering. Soon they would be growing into a civilized community. It was my father's dream. He wanted more doctors and nurses; they would marry, he said, and have children... .

Oh yes, those were dreams he and my mother shared; but it was the fact that they believed my future was settled which delighted them most.

There was another matter. I had noticed one of the plantation overseers, a very tall, handsome young man, was constantly near the house waiting for a glimpse of Cougabel. He liked to take the baby from her and rock him in his arms.

I said to my mother: "I believe Fooca is the father of Cougabel's baby."

"The thought had occurred to me," replied my mother. She laughed. She was laughing a great deal these days.

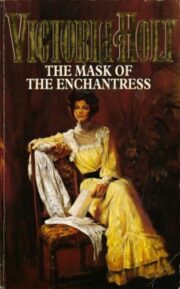

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.