I said: "It's so strange to me ... exciting in a way. Sometimes I feel I am looking at myself."

"The resemblance is not all that marked. Your features are alike. I remember her as a little girl. She was ... mischievous. One doesn't take much notice of that in children. Oh, as I say, I'm being unfair."

"She is very pleasant to us all," I said. "I think she does want us to like her."

"Some people are like that. They supposedly mean no harm ... and in fact do nothing one can point a finger to, but they act as a disturbance to others while seeming innocent of this. We have all changed subtly since she came."

I thought a good deal about that. It was true in a way. My mother had lost her exuberant good spirits; she was thinking a great deal about Jessamy, I knew. My father was living in the past too. It had been a terrible burden to carry, the death of his own brother. He would never need to be reminded of what he had done but he had begun to work out his salvation and he had dedicated himself to saving lives. And now his guilt sat heavily upon him. Moreover somehow the hospital had been belittled. It seemed like a childish game instead of a great endeavor.

Philip had changed too. I did not want to think about Philip. I had believed that he was beginning to love me. When I first went to the property as his sister's friend I had been just a schoolgirl to him. We had enjoyed being together, had talked together and liked the same things. I had been entranced by everything I saw and he had enjoyed introducing me to the great outback. But he had had to get used to the idea that I was growing up. I thought he had when he came to the island. I had, perhaps conceitedly, thought that I was one of the reasons for his coming. My parents had thought so too. We had all been so happy and cozy. The nightmare of that fearful experience that my parents had undergone had receded, although it could never disappear altogether. Now of course it was right over them, brought by Susannah. She could hardly be blamed for that, except that she made it seem as though it had happened yesterday. But Philip? How had she changed him? The fact was that she had bemused him.

Cougabel said to me one day when she met me on the stairs, "Take care of her, she spell maker and she make big spell for Phildo."

Phildo was Philip. He had been amused when he first heard it. It meant Philip the doctor.

Cougabel laid her hand on my arm and gave me an expressive glance from those limpid eyes of hers. "Cougabel watch for you," she said.

Ah, I thought, we are blood sisters again.

I was pleased, of course, to be on better terms with her, but disturbed by what she was hinting—the more so because I knew it was true.

It was natural that Philip should be attracted by Susannah. He had been attracted by me and Susannah was like me but in a more glittering package. The clothes she wore, the manner in which she spoke and walked ... they were alluring. I could imitate her very easily but I scorned to do this. All the same it was rather saddening to stand by and see Philip's interest in me wane while it waxed for Susannah's more sophisticated charms.

My mother was cool to him; so was my father. They must have discussed the change together and it was beginning to occur to them that Susannah—without doing anything but be perfectly charming to us all—was spoiling our plans for the future.

She loved to be with me, and I was fascinated but a little repelled by her.

I felt I had been transported to that magic day when I had seen the castle and there had had my three wishes. There was no doubt that she was obsessed by the castle too. She described it to me in detail ... the inside, that is. The outside was imprinted on my memory forever.

"It's wonderful," she said, "to belong to such a family. I used to like to sit in the great main hall and look up at that high vaulted roof and the lovely carvings of the minstrels' gallery and imagine my ancestors dancing. The Queen came once ... Queen Elizabeth, you know. It's all in the records. The Tudor Matelands were ruined by her coming and had to sell some of the oaks in the park to meet the bills for entertaining her. Another ancestor planted more when he was rewarded after the Restoration for being loyal to Charles. You can see them all in the gallery. Oh yes, it is exciting to belong to such a family ... even though we have robbers, traitors and murderers among us. Oh, sorry. But you mustn't really be so sensitive about Uncle David. He was not a very good man. I'll bet you anything my father had a very good reason for fighting that duel. Besides, a duel is not a real murder. They both agree to fight and one wins, that's all. Oh, I do wish you wouldn't all look so glum when I mention Uncle David."

"It's been on our father's conscience for years. How would you feel if you had killed your brother?"

"Having none, it's difficult to say. But if I killed my half sister I should be very cross with myself, for to tell you the truth I like her more and more every day."

She could say charming things like that and then one believed she never meant to wound.

"Uncle David was a typical Mateland," she went on. "In the old days he would have waylaid travelers and brought them to the castle and made sport with them. There was one who did that long ago in the dark, dark ages. Uncle David would have gone for the women ... fate worse than death and all that. Oh yes, he was very fond of the women. He had his mistresses right under Aunt Emerald's nose. Mind you, she was an invalid, poor soul. And a very trying old lady she is too. As for Elizabeth ... but she's dead now."

"What about Esmond?" I asked.

Her expression changed. "I'll tell you a secret, shall I, Suewellyn? I'm going to marry Esmond."

"Oh, that's wonderful."

"How do you know?"

"Well, if you love him ... and you've been brought up together ..."

"Quite good reasons, but there is another. Shall I tell you what it is? You ought to guess. Can you? No, of course you can't. You're too good. You've been brought up by sweet Anabel ... who was not too sweet to get a child by the husband of her best friend... ."

"Please don't talk about my mother like that."

"I'm sorry, sweet sister. But it was my mother who was her best friend and I was there when she found out. But you're right.

It's not fair to speak of it now. It's not really fair to judge anybody, is it? Only priggish people do that, for how can they know what drives people to act as they do, and how do we know what we should do in similar circumstances?"

"I agree," I said.

"Then you won't judge me too harshly when I tell you I'm going to marry Esmond because he owns the castle."

"And you wouldn't marry him if he didn't?"

"No. It is purely because he owns the castle and I'd marry anyone who owned the castle. I should get it if Esmond died but as Esmond comes first I'd have to marry Esmond or kill him— and marriage is much easier. There, now you're shocked. You think, She is selling herself for a pile of stones and talking about murder as though it is a natural way of life."

I was silent. I was thinking: If she is going to marry Esmond, she will go away and it will be as it was before. Philip and I will be together again.

But it wouldn't be the same, of course.

"Ever since I was a child I was fascinated by the castle," she went on, for once not seeing that my attention had strayed from her affairs to my own. "I used to force myself to go down to the dungeons. I had the children over from the nearby manor house to play with me and I used to make them enter the undercroft— and the crypt leads from there. You go down a few steps and it is dark and cold ... so cold, Suewellyn. It's hard to imagine that cold here. And there are the vaults ... long-dead Matelands all lying in state in those magnificent tombs. One day I shall be there. I shan't change my name when I marry. I shall never be anything but a Mateland. It's very convenient Esmond's being my cousin."

"Does he know of your obsession with the castle?"

"To a certain extent. But, like all men, he is vain. He thinks he must be included in the obsession and that is something I have to let him believe."

"You sound very cynical, Susannah."

"I have to be realistic. Everybody does if they are going to get what they want."

"When are you going to marry Esmond?"

"When I go back probably."

"When is that?"

"When I have seen the world. I was in a finishing school in Paris for a year and when that was over I wanted to complete my education by seeing the world. I was going to do something like the Grand Tour. Then I discovered where my father was, so naturally I changed plans and came out here."

"It was a breach of confidence for this man to tell you."

"I had to be very charming to him. I can if I want to."

"You seem to be ... quite effortlessly."

"It seems so. That's the art of it ... to let it appear effortless. But a lot of work goes into it, you know."

"Sometimes I think you're laughing at me ... laughing at us all."

"It's good to laugh, Suewellyn."

"But not at other people's expense."

"I wouldn't hurt you ... any of you. Why, I love you all. You're my long-lost family."

Her eyes were mocking. I wished that I understood Susannah.

But there was no doubt that her delight in Mateland Castle was genuine. I was growing as enthralled as she was. It seemed as though I wandered through those vaulted rooms with her. I could feel the cold of the vaults, the terror of the dungeons, the eerieness of the undercroft and the splendor of the main hall. I felt that I had actually walked up the great staircase and stood beneath the portraits of those long-dead Matelands, that I had dined in their company in the dining room with its tapestried walls and needlepoint chair seats which had been worked by some long-dead ancestor. I lingered in the Braganza room which the Queen of that name had occupied when she stayed at the castle. I sat on the bay window in the library with books from the shelves piled beside me—and in the main hall and the little breakfast room which the family used for taking meals when they were alone. Then I walked through the armory at night when it was so ghostly with the suits of armor standing there like sentinels. I felt that I had sat in the solarium catching the last of the sun before darkness fell. It was uncanny. I felt that I knew the castle, that I had lived there. I longed to hear of it and continually I plied Susannah with questions.

She was amused. "You see the power of this castle," she said. "You, who have never stepped inside it, long to be there. You would like to possess it, wouldn't you? Oh yes, you would. Imagine yourself mistress of Mateland. Imagine yourself going to the kitchens every morning to discuss the day's menu with the cooks, bustling round the stillroom, counting your preserves, arranging balls and all the amusements which are part of entertaining in a castle. It's because you belong. You're one of us. Our blood is in your veins and if you acquired it on the wrong side of the blanket, as they say, it's still there, isn't it? It's the home of your ancestors. Your roots are sprouting from those ancient stone walls."

There was a good deal in what she said. I would never forget as long as I lived standing at the edge of the woods with Anabel and seeing it for the first time, and how I had watched the riders passing under the gatehouse—Susannah, Esmond, Malcolm and Garth.

Susannah and I spent a great deal of time together. I told her I was going to Laura's wedding and would be leaving with the ship when next it called. "Shall you be leaving too?" I asked.

"I'll think about it," she said. "You'll be away two months. Oh yes, I must come with you. I'll have to make plans for going home. Why don't you come with me? I'd love to show you the castle."

"Come with you! How would you explain me to Esmond ... Emerald and the others?"

"I should say: 'This is my beloved sister. We have become good friends. She is going to stay at the castle.'"

"They would know who I was."

"Why not? You're a Mateland ... one of us, aren't you?"

"I couldn't come. They would ask questions. They would find out where my father is... ."

She shrugged her shoulders. "Think about it," she said, "while you're dancing at this wedding."

"I am leaving in two weeks' time."

"And Philip will go with you. The bride is his sister, isn't she? I'll have to come, I think."

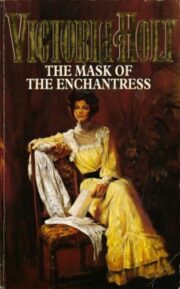

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.