We rode back to the castle. He was talking all the time and I was desperately working hard not to betray myself.

When we came to the stables I had my first piece of luck of the morning.

One of the grooms called out: "So you found Miss Susannah then, Mr. Malcolm."

Then I knew that my companion was the man whom I had cheated of his inheritance.

As we came into the castle Janet was in the hall.

She said: "Good day, Miss Susannah, Mr. Malcolm."

We acknowledged her greeting and I noticed that she was studying me intently.

"Luncheon's in an hour," she said.

"Thanks, Janet," replied Malcolm.

I went to my room and it was not long before Janet came knocking on my door.

"Come in," I called. She came and I was aware of that alert look on her face which I had noticed in the hall.

"You've no idea how long Mr. Malcolm will be staying, Miss Susannah?" she said. "Only Mrs. Bates was asking me. He used to be fond of saffron flavor and she's run out of it. It's not all that easy to get hold of."

"I've no idea how long he's staying."

"Like him to turn up unexpected. He's been turning up like that... oh, ever since your grandfather used to encourage him after the trouble."

"Oh yes," I murmured. "You can never be sure with Malcolm."

"You never got on very well with him, did you?"

"No. I didn't."

"Too much alike, you two, that's what I used to say. You wanted to take over charge of everything ... both of you. I always used to think poor Mr. Esmond got squashed between the two of you."

"I suppose it was a bit like that."

"Well, with you two always at each other's throats ... I used to look forward to Mr. Malcolm's visits. I used to say it was good for you." She looked at me quizzically. "You could be a little demon at times."

"I expect I was rather foolish."

"Well, I never thought I'd hear you say that. I always used to say, 'Miss Susannah always sees one point of view and that's her own.' It was rather the same with Mr. Malcolm. There's no doubt about it though, he's got a great feeling for the castle. And the tenants like him too. Not that they didn't like Mr. Esmond. But he was a bit too soft, and then, of course, he had that way of promising and not carrying out. He gave way always because he wanted to please people. He hated saying no, and so he never did. It was yes, yes, yes, whether he could do it or not."

"That was a mistake."

"I'd agree with you on that, Miss Susannah. But he was well liked. It was a shock to us all when he went like that and the people on the estate mourned him."

I thought it was safe to ask about Esmond's death because I knew Susannah had not been here when it happened.

I said: "I'd like to hear more about Esmond's last illness."

"Well, it was like that time when he was ill. You were here when that happened. He had the same symptoms ... that terrible weakness that came over him suddenly. You remember how he was when you came back from your finishing school. Mr. Garth was here then. It was at the time Saul Cringle killed himself. After that Mr. Esmond seemed to get better. It was all a bit dramatic, wasn't it? Then you decided to go off and find your father. I know how you felt. I'll never forget the day they found Saul Cringle hanging in the barn. Nobody could say why he'd done it. It might have had something to do with that old Moses. He led them all a dance. Saul and Jacob and now the grandchildren. I reckon young Leah and Reuben and Amos have a terrible life of it. But they got the idea somehow that you had something to do with Saul's taking his life. You'd been bothering him, they said ... finding fault... . You were always at Cringles', remember."

"I wanted to see that the estate was running properly."

She looked at me slyly, I thought. "Well, that was for Esmond to see then, wasn't it? They said Saul had been so strictly brought up that he thought he was destined for hell-fire if he did anything that could be the slightest bit wrong. That could explain it."

"How?" I demanded. "If he thought he was destined for hellfire you'd think he'd delay his arrival there."

"That's just what you would say, Miss Susannah. You were always irreverent, you were. I used to say to Mrs. Bates, 'Miss Susannah cares for neither God nor man.' Your mother went in fear for you."

"Oh, my mother ..." I murmured.

"Poor dear lady! She never got over being left like that ... and him going off with her best friend."

"They had their reasons."

"Well, doesn't everybody?" She went to the door, pausing there with her hand on the latch. "Well," she went on, "I'm glad to see you and Mr. Malcolm seem to get on better together. It's early days yet. But you used to be like a cat and dog snarling at each other. I think it's got something to do with the castle. In the old days people used to fight over castles... . All that boiling oil they used to pour down from the battlements ... and the battering rams and the arrows out of the windows ... They did all that to capture the castle. Now they have other ways."

"It's all settled now," I said.

She looked wary. "You were always set on being mistress of the castle. I always thought that was why you decided to marry Esmond. Then of course you got it without marrying him. You're mistress of the castle now, and if Esmond had lived you would have had to share it with him. Not that you wouldn't have had your way. I'm sure you would. But it's different now. You're in complete command."

"Yes," I said; and it struck me as very strange that she should always be seeking me out and that she should talk to me in this way. But I dared not discourage her. I had learned more from Janet than from anyone. And I desperately needed to learn.

She said then: "I'll be getting on and you'll want to tidy up for luncheon."

I couldn't help but be grateful to her. So Malcolm and I were old enemies. He wanted the castle. And he had believed that there was a possibility of his inheriting it on Esmond's death. It must have been a blow to him to realize that I—or rather Susannah—had come before him.

I had to be especially careful now. Malcolm knew Susannah but hadn't seen her for some time. Fortunately they had never been very friendly and had in fact disliked each other; still he had all his faculties about him and nothing would delight him more than to discover this fraud.

This was my test. The rest of them had been comparatively easy compared with him. Emerald might have represented difficulties if she had not been half blind; with Malcolm it would be different. He was shrewd; moreover, nothing would please him more than to discover that I was an impostor, for since Susannah was dead he was in fact the true heir. Only a bogus one stood between him and the castle.

There were only three of us to luncheon and I was filled with trepidation. I wished that I had had longer to prepare for Malcolm.

Emerald at the head of the table peered at him. "I guessed you would soon be with us," she said.

"I didn't know Susannah would be here, and I thought I would just take a look at the estate in case there was something I could do."

"Jeff Carleton was pleased to see you, no doubt."

"I haven't seen him yet. He was out so I went in search of Susannah."

"I could not have been more glad to see you," I told him.

"Well, that is unexpected, I'm sure, Malcolm," put in Emerald.

"It was. And in such circumstances! I think the Cringles should be spoken to. This was going a bit too far."

"I hope there is not going to be trouble," said Emerald, "because it makes me feel quite ill. We've had enough, heaven knows."

"It was those Cringle boys, I assume," said Malcolm.

I thought I had been silent long enough so I cut in: "I was at Cringles' and one of the boys said his cat was trapped in the barn and asked me to help him free it. He took me to the barn and there was ..."

"It was a scarecrow, dressed like Saul," said Malcolm.

"How ... horrible!" cried Emerald.

"He was hanging there ..." I said.

"And he had one of Saul's old caps on," added Malcolm. "I must say it was realistic until the thing turned and you saw the face. It was a nasty shock."

"I should think so. That's why you've been so quiet, Susannah."

"The Cringles have got to put all that behind them," Malcolm put in. "They've got to stop blaming you ... us ... for what happened. Saul wasn't in his right mind, if you ask me." He was looking at me steadily. "The reason he did it may be known to some ... but let it rest, I say."

"Yes," said Emerald, "they should let it rest. The subject makes my head ache."

She then began to talk of a new recipe she had for headaches. She thought it very effective. "There's rosemary in it. Now you wouldn't think that had restful properties, would you?"

I started to talk animatedly about herbs and all the time I was saying to myself: I must find out what Susannah was doing at the time of Saul Cringle's death. That she was involved in it I was sure.

We got through luncheon and Emerald went to her room to rest. I did not ask what Malcolm was doing, but I went to my room with the intention of looking through some of the castle papers.

I wished I could shut out the memory of that horrible hanging figure.

I had avoided reading Esmond's diaries. I had felt reluctant to do so and had laughed at my scruples, which seemed incongruous in one who was perpetrating an imposture which was growing more and more like a criminal act.

At times I had the desire to pack a bag and disappear, leaving a note behind. ... To whom? To Malcolm, telling him that Susannah was dead and I had stepped into her shoes. I had no right here and was going away.

But where to? What should I do? I would quickly be without the means to support myself. Perhaps I could do what I should have done in the beginning: stay with the Halmers until I could find some sort of post.

I could not stay in my room. I felt stifled. So I went out and across the fields to the woods. And there I lay down on the spot where I had stood long ago with Anabel and looked at the castle.

The intensity of my feeling amazed and alarmed me. I was caught in the spell of the castle. I would never willingly give it up. If I did I would yearn to be back forever.

It had bewitched me. I realized that it must have had the same effect on Susannah. She had been ready to marry Esmond to get it; and from what I had heard of Esmond it was becoming increasingly clear to me that she could never have been in love with him. She would have that mild, teasing affection for him which I had associated with her and Philip.

I kept imagining her going into Esmond's room, naked beneath her robe. I sensed his bewilderment and delight. Poor Esmond!

And Susannah? She wanted to be admired, adored. I had been aware of that from the first. I wondered why she had stayed so long on the island. Because of Philip, of course.

Somehow in the shadow of the woods I felt safe. It was as though the spirit of my father and mother hovered over me. I thought back to the first moment of temptation and wondered why I who had hitherto been so law-abiding should have become involved in this trickery. I tried in vain to make excuses for myself. I had lost all whom I had loved. I was without means to support myself. Life had dealt me a cruel blow and then ... this had presented itself to me. Carrying it out had drawn me out of that depression from which I had felt I could never escape. It had made me forget for moments my parents and all that I had lost. But there is no excuse, I told myself.

And yet, as I lay there in the shadow of the trees, I knew that if I had the chance to go back I would do it all over again.

I was startled by the crackle of undergrowth. Someone was close. My heart started to beat uncertainly as Malcolm came through the trees.

"Hello," he said. "I saw you come this way." He threw himself down beside me. "You're upset, aren't you?" He went on scrutinizing me earnestly.

"Well," I temporized, "it was rather an upsetting experience."

He looked at me quizzically. "In the old days ..." he began and stopped. I waited apprehensively for him to go on.

"Yes?" I couldn't stop myself prompting him although I was feeling so uneasy.

"Oh, come, Susannah, you know what you were like. Pretty heartless. Cynical too. I should just have thought you would have looked on it as a sort of practical joke."

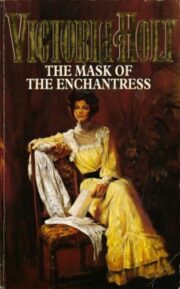

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.