Tom took the poker and knelt down, poking the fire. His face was very red.

Matty was unusually silent.

I could stay no longer but I made up my mind that when I was alone with Matty I was going to ask her why she was so disturbed about this man.

But that opportunity never came.

It had been a mild and misty day. It was almost dark just after three o'clock when I came home from school. As I came to the green I saw the station fly outside Crabtree Cottage and I wondered what it could mean. Miss Anabel always let us know when she was coming.

So I did not call in on Matty as I had intended but ran as fast as I could into the cottage.

Aunt Amelia and Uncle William came out of the parlor as I entered. They looked bewildered.

"You're home," said Aunt Amelia unnecessarily; she gulped and there was a brief silence. Then she said: "Something has happened."

"Miss Anabel ..." I began.

"She's upstairs in your room. You'd better go up. She'll tell you."

I ran up the stairs. There was chaos in my room. My clothes were on the bed and Miss Anabel had begun putting them into a bag.

"Suewellyn!" she cried as I entered. "I'm so glad you're early."

She ran to me and hugged me. Then she said: "You're coming away with me. I can't explain now... . You'll understand later. Oh, Suewellyn, you do want to come!"

"With you, Miss Anabel, of course!"

"I was afraid ... after all, you've been here so long ... I thought... never mind... . I've got your clothes. Is there anything else?"

"There are my books."

"All right then ... get them... ."

"Is it for a holiday?"

"No," she said, "it's for always. You're going to live with me now and ... and ... But I'll tell you about it later. At the moment I want us to catch the train."

"Where are we going?"

"I'm not sure. But a long way. Suewellyn, just help me."

I found the few books I possessed and those with my clothes went into the traveling bag which Miss Anabel had brought with her.

I was quite bewildered. Secretly I had always hoped for something like this. Now it had come I felt too stunned to accept it.

She shut the bag and took my hand.

We paused for a second or so to look round the room. The sparsely furnished room which had been mine for as long as I could remember. Highly polished linoleum, texts on the walls-all improving and all slightly menacing. The one which I had been most conscious of was: "Oh, what a tangled web we weave, when first we practise to deceive!"

I was to remember that in the years to come.

There was the small iron bedstead covered by the patchwork quilt made by Aunt Amelia—each patch surrounded by delicate feather stitching, a sign of commendable industry. "You should start collecting for a patchwork quilt," Aunt Amelia had said. Not now, Aunt Amelia! I am going away from patchwork quilts, cold bedrooms and colder charity forever. I am going away with Miss Anabel.

"Saying good-by to it?" asked Miss Anabel.

I nodded.

"A little sorry?" she asked anxiously.

"No," I said vehemently.

She laughed the laugh I remembered so well, although it was a little different now, more high-pitched, slightly hysterical.

"Come on," she said, "the fly's waiting."

Aunt Amelia and Uncle William were still in the hall.

"I must say, Miss Anabel ..." began Aunt Amelia.

"I know ... I know ... ," replied Anabel. "But it has to be. You will be paid... ."

Uncle William was looking on helplessly.

"What I am wondering is this," went on Aunt Amelia, "what are people going to say?'

"They've been saying things for years," retorted Miss Anabel lightly. "Let them go on."

"It's all very well for them as is not here," said Aunt Amelia.

"Never mind. Never mind. Come on, Suewellyn, or we'll miss our train."

I looked up at Aunt Amelia. "Good-by, Suewellyn," she said, and her lips twitched. She bent down and touched the side of my face with hers, which was as near as she could get to a caress. "Be a good girl ... no matter where you find yourself. Remember to read your Bible and trust in the Lord."

"Yes, Aunt Amelia," I said. "I will."

Then it was Uncle William's turn. He gave me a real kiss.

"Be a good girl," he said, and pressed my hand.

Then Miss Anabel was hurrying me out to the fly.

Of course I am looking back over the years and it is not always easy to remember what happened when one is not quite seven years old. I think the picture gets colored a little; there is much that is forgotten; but I am sure that a wild excitement possessed me and I felt no regret at leaving Crabtree Cottage except for Matty, when I came to think of it, and Tom of course. I should have liked to sit once more by Matty's fire and tell her how I had found Miss Anabel in the cottage packing my things with the fly waiting to take us to the station.

I do remember the train going on and on through the darkness and now and then the lights of a town appearing and how the wheels changed their tune. Going away. Going away. Going away with Anabel.

Miss Anabel held my hand tightly and said: "Are you happy, Suewellyn?"

"Oh yes," I told her.

"And you don't really mind leaving Aunt Amelia and Uncle William?"

"No," I answered. "I loved Matty, and Tom a bit, and Uncle William I liked."

"Of course they looked after you very well. I was very grateful to them."

I was silent. It was so difficult for me to understand.

"Are we going to the woods?" I asked. "Are we going to see the castle?"

"No. We're going a long way."

"To London?" I asked. Miss Brent had often talked about London and it was marked with a big black spot on the map so that I could find it straight away.

"No, no," she said. "Far, far away. On a ship. We're going to sail away from England."

On a ship! I was so excited that I started to bounce up and down on the seat involuntarily. She laughed and hugged me and I thought then that Aunt Amelia would have told me to sit still.

We got out of the train and waited on a platform for another train. Miss Anabel brought bars of chocolate from her bag.

"This will stay the pangs," she said and laughed; although I did not know what she meant I laughed with her and dug my teeth into the delicious chocolate. Aunt Amelia had not allowed chocolate in Crabtree Cottage. Anthony Felton had sometimes brought it to school and took great pleasure in eating it before the rest of us and letting us know how good it was.

It was night when we left the train. Anabel had traveling bags of her own and with mine there seemed to be a good deal of luggage. There was a fly which took us to a hotel where we had a big and luxurious bedroom with a double bed.

"We must be up early in the morning," said Miss Anabel. "Can you get up early in the morning?"

I nodded blissfully. Some food was brought up to our room-hot soup and cold ham, which was delicious; and that night Miss Anabel and I slept in the big bed together.

"Isn't this fun, Suewellyn?" she said. "I always wanted it to be like this."

I didn't want to go to sleep. I was so happy but so tired that I soon did. I awoke to find myself alone in the bed. I remembered where I was and gave a cry of alarm because I thought Miss Anabel had left me.

Then I saw her. She was standing by the window.

"What's the matter, Suewellyn?" she asked.

"I thought you'd gone. I thought you'd left me."

"No," she said, "I'm never going to leave you again. Come here."

I went to the window. I saw a strange sight before me. There were a lot of buildings and what looked like a big ship lying in the middle of them.

"It's the docks," she told me. "Do you see that ship? It will sail this afternoon and we are going to be on it."

The adventure was getting more and more exciting every minute. Not that anything could be more wonderful than being with Miss Anabel.

We had breakfast in our room and then the porter took our bags down and we went in a fly to the docks. All our luggage was taken and we went up a gangway. Clutching my hand tightly in hers, Miss Anabel took me up a flight of stairs to a long passage. We came to a door on which she knocked.

"Who's there?" said a voice.

"We're here," cried Miss Anabel.

The door opened and Joel was standing there.

He just caught Miss Anabel in his arms and held her tightly. Then he picked me up and held me. My heart was beating very fast. I could only think of the wishing bone in the forest.

"I was afraid you wouldn't be able to ..." he began.

"Of course I would be able to," said Miss Anabel. "And I wasn't coming without Suewellyn."

"No, of course not," he said.

"We're safe now," she said, a little anxiously, I thought.

"Not for another three hours ... when we sail... ."

She nodded. "We'll stay here till then."

He looked down at me. "What do you think of this, Suewellyn? A bit of a surprise eh?"

I nodded. I looked round the room, which I learned was called a cabin. There were two beds in it one above the other. Miss Anabel opened a door and I saw another very small room leading from it.

"This is where you'll sleep, Suewellyn."

"Are we going to sleep on the ship then?"

"Oh yes, we're going to sleep here for a long time."

I was just too bewildered to speak. Then Miss Anabel took my hand and we sat together on the lower bed. I was between the two of them.

"There's something I want to tell you," said Miss Anabel. "I'm your mother."

Waves of happiness swept over me. I had a mother and that mother was Miss Anabel. It was the most wonderful thing that could happen. It was better even than going on a ship.

"There's something else," said Miss Anabel; and she waited.

Then Joel said: "And I am your father."

There was a deep silence in the cabin. Then Miss Anabel said: "What are you thinking, Suewellyn?"

"I was thinking that chicken bones are magic. All my three wishes ... they've come true."

Children take so much for granted. It was not long before I felt I had always been on a ship. I was soon accustomed to the rolling and lurching, the pitching and tossing, which had no effect on me though it made some other people ill.

As soon as the ship had been a day at sea and England was far behind us I noticed the change in my parents. They had lost a certain nervousness. They were happier. I vaguely sensed that they were running away from something. But I forgot about that after a while.

We were on the ship for what seemed like forever. Summer had come quite suddenly and quickly when it shouldn't have been summer at all—moreover it was a very hot summer. We sailed on calm blue seas and I would be on deck with Joel or Miss Anabel ... or perhaps both ... watching porpoises, whales, dolphins and flying fish—such things which I had never seen outside picture books.

I had anew name. I was no longer Suewellyn Campion. I was Suewellyn Mateland. I could call myself Suewellyn Campion Mateland, suggested Anabel. Then I wouldn't lose the name I had had for seven years altogether.

Anabel was Mrs. Mateland. She said she thought I shouldn't call her Miss Anabel any more. We discussed what I should call her. Mother sounded formal. Mamma too severe. How we laughed about it. She said at last: "Just call me Anabel. Drop the Miss." That seemed best and I called Joel Father Jo.

I was so happy to have a father and mother. Anabel I loved slavishly. I worshiped her. Joel? Well, I was very much in awe of him. He was so tall and important-looking. I think everyone was a little afraid of him ... even Anabel.

That he was the finest, strongest man in the world I had no doubt. He was like a god. But Anabel was no goddess. She was the most lovely human being I had ever known and nothing could compare with my love for her.

I discovered that Joel was a doctor, for when one of the passengers fell sick he cured her.

"He has saved a lot of people's lives," Anabel told me. "So one ..."

I waited for her to go on but she did not, and I was too busy thinking how wonderfully it had all turned out for me to ask. I had gained not ordinary parents but these two. It was indeed a miracle after having none.

The journey continued. It was always hot and I had to think hard to remember the east wind blowing across the green and how in winter I had to break the thin layer of ice to get the water to wash from the ewer in my bedroom.

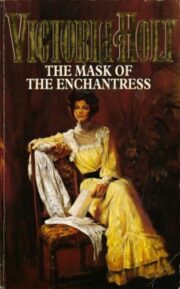

"The Mask of the Enchantress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mask of the Enchantress" друзьям в соцсетях.