Musgrave waved unenthusiastically back.

“You shouldn’t keep my aunt waiting,” said Arabella, enjoying herself just a little too much.

“I came to speak to you on behalf of your aunt,” he said, but his eyes shifted as he said it. He turned to Turnip. “She is very perturbed by the way you have been trifling with her niece.”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake,” said Arabella, twining her arm through Turnip’s. “Nobody is trifling with anyone. We’re quite in accord on that.”

“Perfectly in accord,” echoed Turnip. “In accord as an accordion.”

Musgrave looked at her with concern, and more than a little bit of pity. “You can’t think he means to marry you?”

He meant it, she realized. In his own odd way, he genuinely thought he was protecting her honor. Having not wanted to marry her himself, he assumed no one else would. It would have been amusing if it hadn’t been mildly insulting.

Lowering his voice, Musgrave addressed Turnip. “You do know she doesn’t have a dowry?”

Turnip’s deliberately daft smile never faltered. “That’s quite all right. I do,” he said. Turning to Arabella, he asked, with great seriousness, “Would you prefer it in goats or pigs?”

“Cows,” said Arabella, “definitely cows. You can waylay them for me.”

“Deuced tetchy beasts, cows,” warned Turnip.

“But they make such lovely dairy.”

“Always did like dairy,” agreed Turnip. “Have I mentioned how much I like that dress?”

“You’re both mad,” muttered Musgrave.

“Mad with happiness,” said Turnip. “True love and all that, don’t you know.”

Captain Musgrave looked from one to the other, making a belated attempt to regain control over the situation.

“Does this mean that you do intend to marry?” he asked, with difficulty, as though the idea were such an oddity that it pained him to even entertain it.

“A pertinent question,” Arabella said to Turnip. “What with one thing and another, I don’t believe you ever did officially ask for my hand.”

Turnip whapped himself on the head with the flat of his hand. “Blast this deuced absent mind of mine! Could’ve sworn I had... but, oh well, no harm in doing it again. Would you like the grand display or would a small one do?”

“The grand display,” said Arabella, her lips twitching. “Quite definitely the grand display.”

“I love that about you,” said Turnip abruptly.

Arabella looked quizzically at him. “My instinct for drama?”

“The little lip-twitchy thing you do when you’re trying not to laugh. It’s very high on the list of things I love about you.”

“How long is this list?”

“Hard to tell, really. It keeps growing on me. Deuced inconvenient that way.”

The two shared a long and extremely soppy look.

Arabella fluttered her lashes at him. “I love the way you hit yourself in the head when you’ve forgotten something.”

“Good,” said Turnip, “because I’m deuced forgetful.”

“So long as you don’t forget me.”

Turnip twined his fingers through hers. “Couldn’t do that if I tried. You’re engraved on my heart, don’t you know.”

Arabella batted her eyelashes at him. “How very uncomfortable for you.”

Captain Musgrave peered over his shoulder, checking to see if anyone had heard. “You’re making a scandal of yourself, Arabella,” he said in low, urgent tones.

“Good,” said Arabella cheerfully. “I’ve been far too well-behaved for far too long.”

Shame having failed, Captain Musgrave tried guilt. “If you won’t think of yourself, think of your aunt.”

“I’m not thinking. I’m acting. No more Hamlet for me.” Turnip grinned proudly. It went straight to Arabella’s head. Turning back to her step-uncle, she said giddily, “If you’re not careful, I might invade Scotland next.”

Musgrave looked at her with genuine concern. “I know this year has been difficult for you, but I hadn’t realized quite how difficult. Maybe you should go lie down. You aren’t yourself.”

Arabella smiled ruefully at him, thinking how little he knew. “On the contrary, I am most entirely myself. More so than I’ve been for years.”

Musgrave shook his head in determined negation. “This isn’t the you I know.”

“That’s because you didn’t know me. You wouldn’t have wanted to.” It was true. If she had said half the things she had been thinking, it would have scared him to death. Arabella turned back to Turnip. “As for you, Mr. Fitzhugh, didn’t you promise me a grand display of the scandalous and embarrassing variety?”

“Do my best.” Turnip plopped himself down on one knee where he would be sure to cause the maximum disruption, right in the doorway of the dining room. “Arabella — er, do you have a middle name?”

“Elizabeth.” Arabella was enjoying herself hugely. “You do have troubles with my name, don’t you?”

“Practice makes perfect.” Turnip rubbed his hands together, gearing up for his grand scene. “Right. Here goes. Arabella Elizabeth Dempsey, I adore you. You are the plums in my pudding, the spice in my cider, the holly on my ivy.”

“I don’t think holly grows on ivy,” said Arabella, lips twitching.

“Well, it should,” said Turnip forcefully. “More things in heaven and earth and whatnot. Christmas is a season of miracles.”

A snorting sound came from somewhere above Arabella’s head. It was the dowager, perched high on her litter, wearing a truly alarming headdress of holly and ivy, her sparse gray hair frizzed out like Marie Antoinette in her heyday.

“Say yes, girl!” commanded the Dowager Duchess of Dovedale. “If he keeps talking, I hold you responsible.”

Arabella held out her hands to Turnip, raising him up from his knees. “I love you,” she said, “and I would be honored to be your wife.”

“You don’t mind being Mrs. Turnip?”

“So long as you don’t mind Mr. What’s-Her-Name.”

“Now, that’s a name I can remember,” said Turnip smugly and swept her into his arms, tilting her back at an improbable and wonderfully dizzying angle. “Happy Christmas, my own Arabella.”

Arabella could feel her hair slipping free from its pins in a decidedly wanton way. She smiled up at him. “Aren’t you forgetting something?”

Turnip paused, mid-swoop. “True love, eternal adoration, plum pudding... all seems to be here.”

“There’s just one thing missing.” Raising her head slightly, she flapped a hand in the air, calling out, “Does anyone have any mistletoe?”

An excerpt from the Dempsey Collection :

Miss Jane Austen to Miss Arabella Dempsey

Green Park Buildings, 7 March, 1805

My dear Arabella,

Many thanks for your affectionate letter. I should be delighted to stand godmother to baby Jane, although you have quite ruined my plans for The Watsons. I had intended you for a vicar, not for a wealthy species of vegetable. I refuse to play with puddings and paper scimitars, even for you. You have quite upset my designs, but I forgive you for the excellent diversion your letters provided.

[Several paragraphs omitted]

Thank you for your excellent suggestion regarding the hero in First Impressions. Can you really imagine I would change his name from Darcy to Parsnip?

Yours ever truly,

J. A.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, to Brooke, my little sister, and Claudia Brittenham, the best college roommate in the whole wide world, who both put in massive scads of overtime on this book. Thank you for holding my hand through character conundrums and plot nightmares and for convincing me to retrieve those first six chapters from the recycle bin. I love you both.

To Kara Cesare, my former editor, who cheered me through the beginning of this project, and to Erika Imranyi, my new editor, who valiantly picked it up in the middle. And, as always, to Joe Veltre, my agent, who makes this and all things possible.

To my parents, for being nothing like Arabella’s, and to my friends, for reminding me that there was light at the end of the tunnel.

Last but not least, to Miss Austen, who set the tone for generations of novels to come. What would the world be without Lizzy and Darcy?

Historical Note

In the winter of 1803, Jane Austen was twenty-eight years old and living with her family at Sydney Place, in Bath. Biographers agree that Austen was less than pleased with this arrangement. The move from Steventon to Bath in 1800, just after her twenty-fifth birthday, had been much against her wishes. She found Bath, in her own words, “vapour, shadow, smoke and confusion,” and the people disagreeable. The Bath years were ones of discontent and dead ends. In December of 1802, Austen received a proposal from a family friend, a man of fortune and property, Mr. Harris Bigg-Withers. The proposal must have been a tempting one, to be mistress of her own household — but Austen, having yielded to worldly considerations and accepted his proposal, immediately thought better of it. She rescinded her acceptance the next day and hastened back to Bath. In another disappointment, in 1803, a publisher accepted her novel, Susan (later Northanger Abbey ), but failed to bring it to publication.

Unfortunately, there is little in Austen’s own voice to tell us about this period in her life. Due to the destruction of most of her letters after her death, only 160 remain extant. In this period, the period between 1801 and 1805, only one letter survives, written from Lyme in September of 1804.

What we do know is that towards the end of 1803 Austen began work on a new novel. By 1800, when she made the move to Bath, Austen had already written First Impressions (later Pride and Prejudice ), Elinor and Marianne (later Sense and Sensibility ) and Susan (Northanger Abbey ). Her later works, Mansfield Park, Emma, Persuasion, and Sanditon, were all written much later in her life, after 1812. The Bath years mark a long, fallow period, broken only by one, incomplete work: The Watsons.

The Watsons follows the plight of a young lady, who, like many characters in Austen’s books, has been wrenched from her family as a young child and sent to live with a wealthy aunt in the expectation of becoming her aunt’s heiress. When her aunt contracts an imprudent match to a fortune-hunting army officer, Emma Watson is thrown back upon the bosom of her family: an ailing clergyman father and three unmarried sisters. Critics have commented on the dark tone of this work. In Jane Austen: A Life, Claire Tomalin writes that “[t]he conversations [Austen] wrote for the Watson sisters are strikingly grimmer than anything else in her work,” while in Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels, Deirdre La Faye refers to The Watsons as “a bitter re-run of Pride and Prejudice, ” positing that Austen might have dropped it because it “was becoming too sad,” the situation of Emma and her sisters and their ailing clergyman father being far too close to home.

I borrowed the basic premise of The Watsons for this book, although in Austen’s version, Emma is the youngest sister rather than the oldest. Margaret, Arabella’s most troublesome sister, is lifted straight out of The Watsons, as are the invalid father and Aunt Osborne and the fortune-hunting army officer. Like Arabella, Austen’s Emma Watson plays with the idea of relieving the burden on her family by finding work at a school, a notion her sister strongly deplores. There all resemblance ends. There is no indication in The Watsons that the aunt’s second husband had previously courted Emma, nor are there any French spies or English gentlemen named after vegetables.

Even more telling, Austen’s heroine decides not to take up work at a school; mine does. From her own school days at Mrs. La Tournelle’s Ladies’ Boarding School at Reading, Austen retained a distaste for young ladies’ scholastic institutions that came out loud and clear in her novels. The school in which I place Arabella is a larger, more luxurious version of the institutions with which Austen would have been familiar. Like Miss Climpson, Mrs. La Tournelle hired a number of young woman teachers who conducted the actual instruction, while she presided over the institution. For the sake of my story (and since this was a rather more luxe institution than the one Austen attended), I gave the girls private rooms; at Mrs. La Tournelle’s they would have slept six to a room.

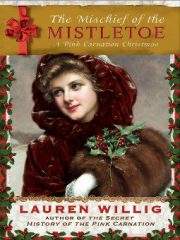

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.