“Most of the time?” repeated Miss Dempsey as she hurried along beside him into the foyer. Turnip pretended not to hear her.

“Right this way!” he said with exaggerated cheerfulness. “Can’t think they will have gone far. When I saw them last they were — ah, right. Here we go.”

The three girls were still together in the blue salon, their heads together, cackling like those three hags in that play he had slept through last month. Something to do with a Scotsman.

Miss Dempsey, he noticed, was still limping slightly, undoubtedly from her tumble on the cobbles. Pluck to the backbone, she was, he thought admiringly. Not a word of complaint out of her.

The same couldn’t be said of Sally.

“Reggie!” exclaimed Sally, her pearl earbobs swinging as she jumped up. Technically, Miss Climpson’s girls weren’t supposed to wear earbobs, but Sally was firmly of the opinion that foolish rules were for other people. “What are you doing back so soon? When I told you to be early, I didn’t mean this early.”

“Oh, ha, ha,” said Turnip cleverly. “What’s the idea of giving me a pudding with a message in it? Oh, this is Miss Dempsey. Miss Dempsey, my sister Sally and her two most peculiar friends.”

“You mean my two most particular friends,” corrected Sally through gritted teeth. Donning the mask of sweetness she wore in front of non-family members, she dipped into a curtsy. “Miss Dempsey. How did you ever come to be associated with my ridiculous brother?”

Miss Dempsey extended the cloth. “We were brought together by an accident of pudding.”

“The one you gave me,” Turnip prompted, looking sternly at Sally. “A thief knocked Miss Dempsey over in an attempt to retrieve it.”

“Really?” Lizzy Reid’s eyes were as round as... well, as very round things. “A footpad? How simply smashing!”

“Yes, if you’re the pudding. It was quite smashed, and so was Miss Dempsey.”

“I wouldn’t say I was quite smashed. Just a trifle shaken.” Taking the chair that Turnip offered her, Miss Dempsey turned to the girls. “The odd thing about it was that there was a message on the pudding cloth. Would you know anything about that?”

“What sort of message?” asked Lizzy.

Miss Dempsey and Turnip exchanged a look. Turnip nodded slightly, and Miss Dempsey went on, “The message appears to be an invitation to an assignation. It was written in French.”

Agnes Wooliston sat up straighter in her chair. “In French?”

Sally ignored the linguistic angle. “That wasn’t the pudding you were planning to send to your brother in India, was it? Lizzy has a brother in India,” Sally added, turning to Arabella.

“Two of them, in fact,” said Lizzy. “But only one gets pudding. The other is currently In Disgrace. No, I already sent Alex’s Christmas basket. Who else do you think could be going about sending messages in puddings?”

“I’d say Catherine Carruthers,” said Sally authoritatively, “but she’s already been found out and put under house arrest. Besides, I think her artist was English, not French.”

“It was a half-pay officer,” corrected Agnes. “And he was quite definitely English.”

“I can assure you, brother mine,” said Sally, “that I have not been arranging assignations. The pudding was here in the parlor when we came in. Wasn’t it, Agnes?”

“Ye-es... ,” said her friend, scanning the room as though trying to fix in her memory where she had seen it. “On the windowsill, there. That was how you came to pick it up. You were standing next to it.”

“And you’d not seen it before?” asked Miss Dempsey quietly.

The three girls looked at one another. They all shook their heads.

“There is such a lot of Christmas pudding going about right now, you see,” said Agnes apologetically, “with everyone getting their Christmas hampers. It’s hard to remember every one.”

“Except for the one with the live chickens,” put in Lizzy Reid helpfully. “That was a very memorable hamper.”

“Do. Not. Mention. The chickens,” said Sally darkly.

“She has an unaccountable fear of fowl,” explained Turnip to Miss Dempsey in an aside.

“They are nasty, they are smelly, and they peck,” said Sally passionately. “Does anyone else have anything more to say on the matter?”

“What about eggs?” There was a glint of mischief in Lizzy Reid’s eye. Turnip began to understand why she had been sent back from India. India probably didn’t know what to do with her.

“Eggs,” said Sally repressively, “grow into chickens.”

“Could the message in the pudding be a prank?” interjected Miss Dempsey, intervening before the eggs hatched into full-blown fighting cocks. “You do have pranks here, I take it?”

“Oh, don’t they!” contributed Turnip feelingly. That had been his last visit. He had been forced to endure a very trying hour with the headmistress, trying to explain why Sally’s tying another girl’s corset ribbons to a drainpipe was nothing more than a case of girlish high spirits and not a cause for sending Sally home. Fortunately, the other girl hadn’t actually been in her corset at the time.

“Traitor,” said Sally, but in a very perfunctory way. She turned back to Miss Dempsey. “This hasn’t any of the... the...”

“Properties?” provided Agnes.

Sally nodded regally. “Thank you. This hasn’t any of the properties of a proper prank. First, you can’t tell at whom it’s aimed. Second, none of us has the slightest way of getting all the way out to Farley Castle. It’s not like sneaking out the back way to go shopping for a bunch of ribbons, you know.”

Turnip looked suspiciously at his sister. “About this back way...”

“And third,” Agnes broke in hastily, before Turnip could ask awkward questions about their illicit extracurricular wanderings, “it’s in French! And we all know what French means.”

She uttered that last in such portentous tones that Turnip began to wonder if he had misread the text on the pudding. He scratched his head and squinted at the piece of muslin lying open on the tea table.

“I know what that French means,” he said cautiously. “It means ‘Meet me at Farley Castle.’ Doesn’t it?”

“That is, indeed, in accord with my translation of it, Mr. Fitzhugh,” said Miss Dempsey.

None of the girls paid the slightest bit of attention to either of them.

“But of course!” said Sally breathlessly, just as Lizzy Reid leaned forward in her chair and exclaimed, “But you can’t really think...”

“Oh, but I do!” said Agnes.

Turning to Turnip, Miss Dempsey said, “Do you think?”

“As little as I can,” Turnip replied honestly. “Do you have any notion what they’re on about?”

“Chickens?” she provided, in such a droll way that Turnip felt his face break into a broad grin. He might even have chuckled.

Jolly good sport, Miss Dempsey.

Sally directed a reproving look at both of them. “This is far, far worse than chickens,” she said with relish.

“Then it must be serious,” murmured Miss Dempsey with all due gravity. Only Turnip noticed the corner of her lips twitch.

“Very serious,” agreed Agnes Wooliston solemnly. “Who would have thought that even here, one would find... spies!”

The announcement had less than the desired impact on the two adults in the room.

“Spies,” said Miss Dempsey. “Spies?”

“I wouldn’t have thought it,” said Turnip bluntly. “In fact, I don’t think it.”

“Oh, you.” Sally waved a dismissive hand. “You never think.”

“I still don’t quite understand,” said Miss Dempsey. “On what are these spies meant to be spying?”

The three girls looked at one another. Clearly, this was not a detail they had considered.

“On... something,” said Agnes.

Her peers nodded vigorously.

Something was obviously the order of the day, and a commodity for which the French were bound to pay dearly.

“Something,” repeated Turnip. He might be the greatest nodcock since the Prince of Wales had ventured into experiments with corsetry, but even he knew a dodge when he heard one.

“Well, think about it,” said Sally impatiently. “There must be oodles on which a spy could spy if he wanted to.”

“I say, Sal, I’ve browsed through your journal, and there ain’t much there of note.”

Sally’s eyes shot sparks of fire. “You’ve read my journal!”

Turnip slunk down in his chair. “I only did it because the mater asked me to. Afraid you were developing a bit of a tendre for that music master of yours.”

“Signor Marconi?” This on dit was too good to pass by. Lizzy bounced around in her chair. “You must be joking!”

“He had very nice mustaches,” mumbled Sally, doing some slinking of her own. Straightening, she gave her brother a look of death. “And I’ll thank you to stay out of my private papers!”

Turnip tapped a finger against his forehead. “Word of advice, sister mine. If you want to keep your papers private, don’t write ‘Private’ on the cover. It set the mater right off. It was all I could do to stop her sniffing around like some great sniffing thing.”

“Hmph,” sniffed Sally.

As a sniff, it wasn’t quite up to the maternal standard, but, to be fair, their mother had had years more of practice. Put a little more air into it, and Sally would be bang up to the mark in no time.

“I don’t think he’s a spy,” said Agnes thoughtfully, bringing the discussion back where it belonged. “Signor Marconi, I mean.”

“What about the new French mistress?” suggested Sally spiritedly, bouncing in her chair as she turned to her peers for confirmation. “She is awfully French.”

“Do you mean just because she speeeeeek lak zees?” contributed Lizzy, with an innocence belied by the wicked sparkle in her brown eyes.

“It’s a nice idea, but Mademoiselle Fayette does make rather a fuss about her brother’s head being chopped off,” Agnes pointed out. “That might make one rather less inclined than otherwise to cooperate with the current regime.”

“But how do we know whether she actually liked her brother?” said Sally, with a relish that made Turnip clutch protectively at his own neck. “That might be nothing more than a... than a...”

“Cunning ruse!” supplied Lizzy triumphantly.

“Not so cunning if one can see through it,” said Agnes, disgusted by the poor quality of villains nowadays. “If it were really cunning, it would be so cunning we’d have no idea at all how cunning it was.”

Turnip’s brow furrowed as he attempted to unravel the tangle of cunning.

“How... cunning,” said Miss Dempsey politely. “But whatever would spies be doing at a young ladies’ seminary in Bath?”

“They’re everywhere,” said Agnes earnestly. As if for confirmation, she added, all in a rush, “My cousin married the Purple Gentian!”

“Did she, by Gad!” Turnip smacked the flat of his hand against one knee as it all became clear. Wooliston... ha! That was where he had heard the name before. His friend Lord Richard Selwick, more dramatically known as the Purple Gentian, had married a young lady of half-French extraction who had spent her youth with cousins named Wooliston. Now that he knew who she was, Turnip could see the resemblance in the younger sister.

Ha! Who would have thought to find Selwick’s cousin by marriage bosom friends with his own little sister. Small world, that, he thought profoundly. He’d have to let Selwick know and they could have a good chuckle over it.

“The Purple who?” said Miss Dempsey faintly.

Sally tossed back her blond braids. “The Purple Gentian. A terribly dashing spy.”

“Not only dashing but terribly dashing, eh, Sal?” Turnip chuckled.

Sally went slightly red about the ears. “Well, a spy in any event,” she said in a dismissive tone, addressing herself solely to Miss Dempsey.

“An English one,” Agnes Wooliston added hastily, just in case anyone might get the wrong idea. “Not French. He married my cousin Amy last year, so we all know a terrible lot about spies now.”

This was obviously a source of both admiration and contention.

Sally shrugged, doing her best to look unimpressed. “There were rumors going about that Reginald might be the Pink Carnation, you know.”

Agnes, with all the distinction afforded by a genuine spy-in-law, gave Sally a faintly pitying look. “But he’s not.”

Sally scrunched her shoulder. “Well, no.”

His sister gave Turnip a look that made it abundantly clear that she considered it nothing short of a breach of his fraternal obligations to have been so remiss as to fail to have been the Pink Carnation.

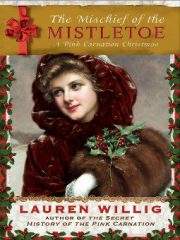

"The Mischief of the Mistletoe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Mischief of the Mistletoe" друзьям в соцсетях.