‘Then one day she was giving a Geography lesson on the rivers of South America when the door opened and a small man in a dark suit and homburg hat came in, carrying a briefcase.

‘The children started tittering but she didn’t even hear them, she just stood and looked at the little man. Then my Uncle Mishak took off his hat — he was pretty bald by then, and he wore gold pince-nez, and he said: “Are you Fräulein Stichter?” He wasn’t really asking, he knew, but he waited till she nodded and then he said: “I have come to fetch you.” Just like that. “I have come to fetch you.” And he opened his briefcase and took out the note from the bottle.’

‘And she came?’

Ruth smiled and parted her hair with her fingers so that she could narrate unimpeded. ‘She didn’t say anything. Not a word. She picked up the duster and very carefully she wiped off the rivers of South America — the Negro and the Madeira and the Amazon. Then she put the chalk back into the box and opened a cupboard and took out her hat and put it on. The children had stopped tittering and started gawping, but she walked down between the desks and she didn’t even see them; they didn’t exist. At the door, Uncle Mishak gave her his arm — he didn’t come much above her shoulder — and they walked across the play yard and down the road and got on the paddle boat for Vienna — and no one there ever saw them again!’

‘And they were happy?’

Ruth put a hand up to her eyes. ‘Ridiculously so. People laughed at them — plumping each other’s cushions, pulling out footstools. When she died he tried to die too, but he couldn’t manage it. That’s when my mother made him come to us.’

Back in the Inner City, Ruth pointed out the balcony on which she had stood stark naked at midnight, at the age of nine, hoping that pneumonia would release her from disgrace and ruin.

‘It was my great-aunt’s flat and I’d just heard that I only got Commended instead of Highly Commended in my music exam. Oh, and look, here’s the actual bench where my mother was overcome by pigeons and my father rescued her.’

‘There seem to have been a lot of happy marriages in your family,’ said Quin.

‘I don’t know… Uncle Mishak was happy, and my parents… but in general I don’t think they thought of it as something that made you happy.’

‘What then?’

Ruth was frowning. One ear turned colour slightly as she strangled it in a loop of hair. ‘It was what you did… because you had set out to do it. It was… work; it was like ploughing a field or painting a picture — you kept on adding colours or trying to get the perspective right. The women in particular. My Aunt Miriam’s husband was unfaithful and she kept ringing my mother and saying she was going to kill him, but when people suggested divorce she was terribly shocked.’ She looked up, her hand flew to her mouth. ‘I’m terribly sorry… I don’t mean us, of course. These were proper marriages, not ones with Morgan.’

Their last visit was to St Stephan’s Cathedral, the city’s symbol and its heart.

‘I’d like to light a candle,’ said Ruth, and he let her go alone up the sombre, incense-scented nave.

Waiting at the door, he saw across the square two terrified fair-haired boys with broad peasant faces being dragged towards an army truck by a group of soldiers.

‘They’re rounding up all the Social Democrats,’ said a plump, middle-aged woman with a feather in her hat. There was no censure in her voice; no emotion in the round, pale eyes.

Making his way to where Ruth knelt, determined to take her out by a side door, Quin found that she had lit not one candle but two. No need to ask for whom — all roads led to Heini for this girl.

‘Shall I ever come back, do you think?’

Quin made no answer. Whether Ruth would return to this doomed city, he did not know, but he and his like would surely do so, for he did not see how this evil could be halted by anything but war.

Chapter 7

Heini had been ten days in Budapest. It was good to be back in his native city; good to walk along the Corso beside the river and look up at the castle on Buda hill; good to see the steamers glide past on their way to the Black Sea and to taste again the fiery gulyás which the Viennese thought they could make, but couldn’t. There was a fizz, an edge of wit here that was missing in the Austrian capital, and the women were the most beautiful in the world. Not that Heini was tempted — he was finding it all too easy to be faithful to Ruth; and anyway one always had to be careful of disease.

His father still lived in the yellow villa on the Hill of the Roses; the apple trees in the garden were in blossom; they took their meals on the verandah looking down over the Pasha’s tomb and the wooded slopes on to the Gothic tracery of the Houses of Parliament and the gables and roofs of Pest.

Heini did not care for his stepmother; she lacked soul, but with his father still editing the only liberal German newspaper in the city, he had to be glad that there was somebody to care for him.

Nor was there any problem about securing a visa for entry into Great Britain. Hungary was still independent, there was no stampede to leave the country; the quota was not yet full. It would take a little longer than he expected — a few weeks — but there was nothing to feel anxious about.

Best of all, Heini’s old Professor of Piano Studies at the Academy had managed to arrange a concert for him.

‘I’d have liked to organize something big for you in the Vigado,’ Professor Sandor said, mentioning the famous concert hall in which Rubinstein had played and Brahms conducted, ‘but it’s too short notice — and who knows, if you play here in the Academy, Bartók may come and that could lead to something.’

Heini had been properly grateful. He remembered the old building with affection; its tradition stretching back to Liszt and boasting now, in Bartók and Kodály and Dohnányi, as distinguished a group of professors as any music school in the world. It was to be an evening recital in the main hall; he was to get half the proceeds; all in all, Professor Sandor had been most helpful and generous.

But there was a snag. The Concert Committee had asked Heini to include in his programme the sonata that the third-year piano students were studying that term: Beethoven’s tricky and beautiful Opus 99. Heini had no objection to this, but though he had the last ten Beethoven sonatas by heart, this one he would have to play from the score — and that meant a page turner.

It was here that things had begun to go wrong. For Professor Sandor had a daughter, also a piano student, whom he had offered Heini in that role.

‘You’ll find her very intelligent,’ the Professor had said proudly; and at Heini’s first rehearsal Mali had duly appeared — and been a disaster.

Mali was not just plain — an unobtrusively plain girl would not have upset him — she was virulently ugly; her spectacles glinted and caught the light; she had buck teeth. Not only that, but she drove him nearly mad with her humble eagerness, her desperate desire to be of use, and though she could hardly fail to be able to read music, she was so hesitant, so terrified of being hasty, that several times he had had to nod at the bottom of the page. Worst of all, Mali perspired.

Heini had missed Ruth ever since he had come to Budapest, but in the days leading up to the concert his longing for her became a constant ache. Ruth turned over so gracefully, so skilfully that one hardly knew she was there; she smelled sweetly and faintly of lavender shampoo and never, in the years she’d sat beside him, had he found it necessary to nod.

Nor was his stepmother at all aware of the kind of pressures that playing in public put on him. Heini’s hands were insured, of course, and taking care of them had become second nature, but a pianist used all his body and when he tripped over a dustpan she had left on the stairs, he could not help being upset.

‘I’m not being fussy,’ he said to Marta, ‘but if I sprained my ankle, I wouldn’t be able to pedal for a month.’

It had been so different in the Bergers’ apartment, which had become his second home. Not only Ruth but her mother and the maids were happy to serve him, as he in turn served music.

But it was on the actual day of the concert that Heini’s need for Ruth became almost uncontainable.

The day began badly, when he was woken at nine o’clock by the sound of the maid hoovering the corridor outside his room. He always slept late on the day of a concert, but when he complained, his stepmother said that the girl had to get through her work and pointed out that Heini had already spent ten hours in bed.

‘In bed, but not asleep,’ Heini said bitterly — but he didn’t really expect her to understand.

Then there was the question of lunch. Heini could never eat anything heavy before he played and in Vienna Ruth always made a point of getting to the Café Museum early to keep a corner table and make sure that the beef broth, which was all that he could swallow, was properly strained and the plain rusks well baked. Whereas Marta seemed to expect him to play on a diet of roast pork and dumplings!

Leaving the house earlier than he had intended, Heini, walking down the fashionable Váci utca, faced yet another challenge: the purchase of a flower for his buttonhole. A gardenia was probably too formal for the Academy, a camellia too, but a carnation, a white one, should strike the right note. Ruth, of course, had bought his buttonholes — he had watched her once, searching for a flawless bloom, involving the shop assistant, who knew her well, in the excitement of kitting him out.

Bravely now, Heini went in alone and found a girl to help him. It was only when he came out again, his flower safe in cellophane, that he realized that he did not have a pin.

In the hall of the Academy, Professor Sandor was waiting.

‘It’s an excellent attendance — almost full. Considering we had less than two weeks for the publicity and there’s a premiere at the opera, we can be very pleased.’

Heini nodded and went to the green-room — and there was Mali in an unbelievably ugly dress: crimson crepe which clung unsuitably to her bosom and exposed her collar bones. The splash of colour would distract the eye even from the back of the hall. Ruth always chose dresses that blended with the colours of the hall, quiet dresses which nevertheless became her wonderfully.

‘Do you have a pin?’ he asked — and Mali did at least have that and managed, fumbling and nervous, to fasten the carnation in his buttonhole. ‘I shall need to be quiet now,’ he added firmly, and sat down as far away from her as possible.

Not that this ensured him the peace he craved. Mali fidgeted incessantly with the Beethoven sonatas, checking the pages; she cleared her throat…

Ruth knew exactly how to quieten him during those last moments before a concert or an exam. She brought along a set of dominos and they played for a while, or she just sat silently with her hands folded and that marvellous hair of hers bright and burnished, but taken back with a velvet band so that it didn’t tumble forward and distract the audience. Ruth made sure he had fresh lemonade waiting for him in the interval; he never had to think about his music, it was always there and in the right order. And now, glancing in the mirror, he saw that his carnation was listing quite noticeably towards the left!

‘Five minutes,’ called the page, knocking on the door.

‘My handkerchief!’ said Heini suddenly in a panic. The white one in the pocket of his dinner jacket was there, of course, but the other one, the one with which he wiped his hands between the pieces…

Mali flushed and jumped to her feet. ‘I’m sorry… I didn’t know that I…’

‘It doesn’t matter.’ He found the one his stepmother had washed for him, but cotton, not linen. The Bergers’ maids always laundered his handkerchiefs; they smelled so fresh and clean with just the lightest touch of starch: Ruth saw to that.

It was time to go. Professor Sandor put his head round the door. ‘Bartók is here!’ he said, beaming — and Heini rose.

The applause which greeted him was loud and enthusiastic for Heini Radek was an amazingly personable young man with his dark curls, his graceful body. This was how a pianist should look and in Liszt’s city comparisons were not hard to make.

Heini bowed, smiled at a girl in the front row, again up at the gallery, gave a respectful nod in the direction of Hungary’s greatest composer. Turning to settle himself on the piano stool he found that Mali, her Adam’s apple working, was leaning forward in her chair. He had told her again and again that she had to sit back, that the audience must not be aware of any figure but his, and she jerked backwards. It was unbelievable — how could anyone be so gauche? And she had drenched herself with some appalling sickly scent beneath which the odour of sweat was still discernible.

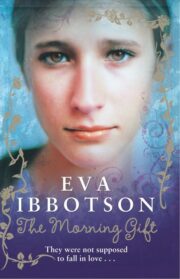

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.