Now, dialling the university, he was put through at once to Felton in his laboratory. His deputy taught the Marine Biology course, as well as dealing with admissions: a friendly man, deeply concerned about the students, whose spectacle frames seemed to lighten or darken according to his mood.

‘Oh, you’re back, are you?’ said Felton.

Since Quin himself had abolished the protocol and rank-pulling which still existed in so many university departments, he now had to endure some strong remarks about professors who left their underlings to mark their exam papers while they gallivanted about in foreign cities.

‘It wasn’t quite like that — but I’m sorry about the extra load. How have they done?’

‘Oh, brilliantly on your questions, of course. I dare say you could teach Palaeontology to a chimpanzee and get him a First. The new intake looks promising too — numbers are up again.’

‘You haven’t had any applications from refugee organizations, have you? University College is taking foreign students, I know.’

‘Not so far.’

‘Well, if you get any, accept them — it’s hell over there, I can tell you. Even if it means putting them to work in a broom cupboard, say yes.’

‘All right, I will. Though I don’t know what the new VC will say; he doesn’t seem to be much of a one for the huddled masses yearning to breathe free.’

‘Plackett’s a dud, is he?’

‘He’s one of those faceless men — adores committees. The paperwork’s trebled since he came, but there’s no harm in him; it’s his wife that’s the bother. Wants to improve the moral tone of the university and makes the college servants run her errands. She’s a Croft-Ellis by birth — one of the Rutland Croft-Ellises. Mean anything to you?’

‘Nothing earth shattering.’

‘But that’s not all,’ said Felton ghoulishly. ‘There’s a daughter!’

‘There usually is, I’ve found,’ said Quin resignedly.

‘Ah, but it’s worse than that! She’s coming to us to do a Zoology degree and she’s going straight into the third year because she’s covered most of the ground in India. I interviewed her last week and she was kind enough to tell me that she thought our course would be acceptable.’

‘Good God,’ said Quin.

‘Exactly so.’

Quin spent the next two days in the Natural History Museum, supervising the disposal of the specimens which Milner had steered safely through the customs. Thameside he avoided, deciding to go up to Bowmont first and come back to prepare for the autumn term when the man who was filling in as visiting Professor had gone back to the States. Professor Robinson was prone to anxiety: he had worried because Quin’s name was still on the door of his room, and about the length of his gown, and it seemed tactful to let him complete his tenure without interference.

But there was one chore which he intended to tackle before he went north: the undoing of his marriage.

The affairs of Bowmont were in the hands of a long-established and dozy firm of solicitors in Berwick-upon-Tweed, but for quick action in this highly personal matter, Quin had selected Dick Proud-foot, of Proudfoot, Buckley and Snaith, whom he had known in Cambridge.

Proudfoot was in his early thirties, a chubby, balding man whose amiable expression became considerably less amiable as Quin began to speak.

‘You have done what?’

‘I have married an Austrian girl to get her over here. She’s partly Jewish and she was in danger — there was nothing else to do. Now I want you to get me a divorce as quickly as you can. I’ll provide the evidence, of course. I imagine that business still works about being caught in bed in a hotel by the chambermaid?’

‘Funny, I thought you were intelligent,’ said Mr Proudfoot nastily. ‘I remember people saying it in Cambridge. What sort of quixotic idiocy is this? Even if it were possible for you to convince the judge that this kind of caper represents a genuine adultery — and they’re getting very suspicious these days — it would hardly secure you a speedy divorce. You can’t even begin to petition till three years after the marriage.’

Quin frowned. ‘I thought the Herbert Act had changed all that? The poor man worked hard enough to get it through.’

‘It has increased the grounds on which a divorce may be granted, but in this case the three-year clause still stands.’

‘Well, it’ll have to be an annulment then,’ said Quin cheerfully. ‘That was my first idea, but it sounded a bit ecclesiastical.’

Mr Proudfoot sighed and wrote something on a piece of paper. The laws on nullity were archaic and complex, and his subject was company law. ‘What do you suggest? Nullity can be declared if one or both parties are under sixteen at the time of the ceremony, if there is a pre-existing marriage, if the parties are related by prohibited degrees of consanguinity, if there is insanity in one partner unknown to the other at the time of the marriage, or if the bride is a nun.’

Quin waved an impatient hand. ‘Well, she’s not my sister or a nun and she’s not technically insane unless trying to swim out of Switzerland with a rucksack can be regarded as mental derangement. What else?’

‘There is nonconsummation,’ said Mr Proudfoot reluctantly, seeing minefields ahead.

‘That’s the one,’ said Quin cheerfully. ‘I spent our bridal night in the corridor of the Orient Express.’

‘You may have to prove it.’ The lawyer made another note, adding snarkily that he presumed Quin would plead wilful refusal to consummate rather than incapacity. ‘And there’s another difficulty’

‘What’s that?’

‘Well, you married this girl to give her British citizenship. But if you prove nullity ex causa precedenti — that is to say if you dissolve the marriage on grounds existing before it took place — then it is possible that the British citizenship which followed from the marriage could be imperilled. Of course, nonconsummation isn’t in this category, but if she’s under twenty-one we could be in trouble. The naturalization of minors is under review, but in my opinion we’d be unwise to go for nullity until her status as a British subject is confirmed and she has her own passport.’

Quin looked at his watch. ‘Look, do what you can, Dick, and as quickly as possible. The girl’s very young and she’s in love with a soulful concert pianist. Oh, and write to her, will you, and say we’re putting it through as fast as we can. Offer her any help she needs and charge it to me, but I think it’s best if I don’t see her again.’

‘That isn’t just best, it’s absolutely essential,’ said Mr Proudfoot. ‘If there’s anything that can scupper any kind of divorce or annulment, it’s the three Cs.’

‘The three whats?’

‘Connivance. Collusion. Consent. Any suspicion that you’ve been fixing things between you and the courts will throw out the evidence then and there.’

‘Good God! You mean they’d rather we parted in anger than sensibly and in accord?’

‘That is precisely what I mean,’ said Mr Proudfoot.

Chapter 11

It was hot, the summer of 1938. In the streets of Belsize Park and Swiss Cottage and Finchley, the pavements glittered, the dustbins gave out Rabelaisian smells. In the ill-equipped kitchens of the lodging houses, milk turned sour and expiring flies buzzed dismally on strips of sticky paper. Children in buggies were pushed up the hill to Hampstead Heath to picnic in the yellowing grass or catch tiddlers in Whitestone Pond. In Spain, Franco’s Fascists scored victory upon victory; in Germany, Hitler stepped up his tirades about the Sudetenland, ready to move against the Czechs. Mussolini started to ape, though less effectively, the Führer’s measures against the Jews.

The British would have found it vulgar to let the ill-bred ravings of foreigners interfere with their pleasures. Trenches were dug in the parks, leaflets were issued giving instructions about the issue of gas masks; the fleet stood ready. But the rich left without signs of perturbation for their grouse moors or houses by the sea. The poor, as always, stayed behind and took the sunshine on their doorsteps or in their tiny gardens.

The refugees were poor and they stayed.

Ruth’s arrival had enabled her family to try to reconstitute their lives. Professor Berger now left for the public library each morning with his briefcase, to sit between Dr Levy and a tramp with holes in his shoes who came to read the paper, and hid from Leonie, and partly even from himself, the knowledge that without the references and notes he had left behind, his book could only be a travesty of what he might have written. Aunt Hilda, having discovered that entry to the British Museum was free, spent hours wandering round the Anthropology section and found (among the exhibits from Bechuanaland) an error which caused her the kind of excited melancholy so common in scholars presented with other people’s follies.

‘It is not a Mi-Mi drinking cup,’ she would say each evening. ‘I am quite certain. The attribution is wrong.’

‘Well then, go and tell someone, Hilda,’ Leonie would suggest.

‘No. I am only a guest in this country. I have no right.’

Uncle Mishak now had park benches he had made his own, and friends among the gardeners who kept London’s squares and gardens tidy. Like a small boy, he would come home with treasures: a clump of wallflowers which still retained their scent, thrown onto a compost heap; a few cherries dropped onto a pavement from an overhanging branch. As for Leonie, once she’d accepted the miracle of Ruth’s return, she began to repair the network of friends and relations, of good causes and lame dogs, that had filled her life in Vienna. Dispersed and scattered these might be, but there was still her godmother’s sister, newly arrived in Swiss Cottage, a schoolfriend married to a bookbinder in Putney, and an ancient step-uncle from Moravia, a little touched in the head, who sat under the statue of Queen Victoria on the Embankment, convinced that she was Maria Theresia and he was still in his native city.

As for the ladies of the Willow Tea Rooms, they responded to the worsening of the situation in Europe with a gesture of great daring. They decided to stay open in the evening — to the almost sinfully late hour of nine o’clock. This, however, meant engaging a new waitress — and here they were extremely fortunate.

Ruth’s first concern when she arrived had been to hide her marriage certificate and all other evidence of her involvement with Professor Somerville whom she could now only serve by never going near him or mentioning his name.

This was not as easy as it sounded. Number 27 Belsize Close was not a place where privacy was high on the list of priorities, nor had Ruth ever had to have secrets from her parents. Fortunately she had read many English adventure stories in which intrepid boys and girls buried treasure beneath the loose floor-boards of whatever house they lived in. Accustomed to the solid parquet floors of her native city, she had been puzzled by this, but now she understood how it could be done. The floor of the Bergers’ sitting room, hideously furnished with a sagging moquette sofa, a fumed oak table and brown chenille curtains, was covered in linoleum, and her parents’ bedroom next to it was obviously unsuitable. But in the room at the back, with its two narrow beds, which Ruth shared with her Aunt Hilda, the floor was covered only by a soiled rag rug. Dragging aside the wash-stand, she managed to prise open one of the splintered boards and make a space into which she lowered a biscuit tin decorated with a picture of the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret Rose patting a corgi dog, and containing her documents and the wedding ring which she meant to sell, but not just yet.

Next she went to the post office and secured a box number to which all mail could be sent, and wrote to Mr Proudfoot to tell him what she had done. After which she settled down to look for work. It was nearly two months before the beginning of the autumn term at University College and though she had heeded Quin’s admonitions and was looking forward very much to being a student once again, she intended to spend every available second till then helping her family.

Jobs as mother’s helps were easy to come by. Within a week, Ruth found herself trailing across Hampstead Heath in charge of the three progressively educated children of a lady weaver. Untroubled by theories on infant care, she felt sorry for the pale, confused, abominably behaved little creatures in their soiled linen smocks, desperately searching for something they were not allowed to do. When the middle one, a six-year-old boy, ran across a busy road, she smacked him hard on the leg which caused instant uproar among his siblings.

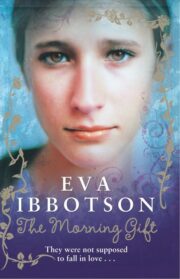

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.