The puppy had been conveyed to the carpenter’s house before breakfast, but Martha’s kind, round face looked unaccustomedly shifty. ‘No, he hasn’t. He won’t have him.’

‘Won’t have him?’ Miss Somerville was incredulous. ‘Did you point out that the work on the pews is two months overdue?’

‘Yes, I did. He says his wife’s got asthma and she’s expecting and the doctor said she wasn’t to go near anything with hair.’

‘I must say I find that extraordinary. People like that wouldn’t have heard of asthma in the old days. It makes you wonder whether education is such a good thing.’ She bent to pick up her gardening trug. ‘Where is it, then?’

‘He offered to shoot it for me,’ said Martha. ‘He said it wouldn’t feel a thing — well, that’s true enough; he’s done enough poaching in his time, Barker has — he could knock down a hare at fifty yards and no trouble.’

Miss Somerville straightened her back. Her face was expressionless.

‘So you agreed? It’s been shot?’

‘No, I didn’t,’ said Martha shortly, and watched her employer’s hands relax on the handle of the trug. ‘Drowning the things at birth before their eyes are open is one thing, but shooting them in cold blood is another. If you want it shot, you can give the instructions yourself.’

‘Where is it, then?’

‘One of the students took it. I met her coming up for the milk. She says she’ll keep it; they’re off to Howcroft Point, I thought she might as well with Lady Plackett not being too fond of it and company coming.’

Miss Somerville nodded. The Rothleys were coming for drinks and the Stanton-Derbys, to welcome Verena and talk about the dance, and she didn’t really want any more jokes about the little dog. She was setting off across the lawn when Martha said: ‘Who’s this Richard Wagner, then? Some kind of musician fellow?’

‘He was a composer. An extremely noisy one, with a reprehensible private life. Why?’

‘This girl… the one who’s taken the puppy… she said he had a step-daughter with eyes like that — Wagner did. One blue and one brown, same as the puppy. Daniella she was called.’

‘The student?’

‘No, the stepdaughter.’

Deciding not to pursue the matter, Miss Somerville made her way to the garden. She thought she would postpone talking to Lady Plackett about the extraordinary behaviour of the carpenter. After all, it was none of her business.

Ruth, meanwhile, had reached the boathouse.

‘What is it?’ enquired Dr Elke, looking at Comely’s love child which was climbing with passionate enthusiasm over her feet.

‘It’s a mixture,’ admitted Ruth.

Dr Elke said she could see that and removed her shoe from the puppy’s grasp.

‘But full of personality?’ suggested Ruth. ‘Though not perhaps strictly beautiful.’

‘No, not strictly.’

‘Voltaire wasn’t beautiful either,’ said Ruth, ‘but he used to say that if he had half an hour to explain away his face, he could seduce the Queen of France.’

‘More than half an hour would be necessary in this case,’ said Dr Elke, and told Ruth to pass the hammers, for she was checking supplies for the day’s fossil hunting on the cliffs off Howcroft Point.

Ruth did so. There was a pause. Then: ‘I thought he might come with us on the bus? Martha said he was very fond of transportation and he’s never sick.’

‘Ask the Professor,’ said Elke and went into the lab.

Since Quin at that moment came down the path, Ruth repeated her request.

‘I thought he might be useful,’ she said.

‘Really?’ Quin’s eyebrows were raised in enquiry. ‘What sort of usefulness had you in mind?’

‘Well, dogs are always digging up bones. Suppose he found something interesting? The femur of a torosaurus, perhaps?’

‘That would certainly be interesting on the coal measures,’ said Quin drily. But seeing Ruth’s face, he relented. ‘Keep him out of the way; I suppose he can’t do much harm on the moors.’

By the time the bus deposited them at Howcroft Point, the puppy had acquired the kind of following that Voltaire himself would have envied. Pilly had held him on her knees throughout the journey, Janet spoke to him in a voice which made Ruth understand what happened in the backs of motor cars, and Huw was on hand to lift him over boulders which defeated even his intrepid scramblings.

It was another perfect day. The cliffs here were topped by heather and gorse, the curlews called — but the work now was hard. For here, in the carboniferous outcrop which ran from the moors out onto the shore, were embedded those creatures that determined all subsequent life on earth. Fragments of ancient corals, whorled molluscs, each characteristic of the layered zones, had to be prised from the rock, labelled, wrapped and carried back to the laboratory. And since no day is complete without the chance for self-improvement, Ruth was fortunate, for the opportunities for loving Verena Plackett on Howcroft Point were endless. Always at the Professor’s heels, she tapped unerringly with her brand-new hammer, finding not only an undoubted specimen of caninia, but also a crinoid complete with tentacles — and laughed merrily whenever Pilly mispronounced a word.

Since the tide was high, they had lunch above the strand on a patch of heather while the puppy consumed sandwiches, fell in and out of rabbit holes and fell suddenly and utterly asleep on Huw’s collecting bag. Most of the students too were glad to be lazy, but Ruth, accustomed to the ascent of high places from which to say ‘Wunderbar!’ scrambled to the top of the hill which commanded a view of the coast for miles, and the moors inland, still showing glimmers of purple. It was not till she caught the whiff of tobacco from behind a boulder that she realized she was not alone.

‘It’s quite something, isn’t it?’ said Quin, gesturing with his pipe at the low line of Holy Island to the south, and the dramatic pinnacle of Howcroft Rock. ‘I’m glad you’ve seen it like this — autumn and winter are best for the colours.’

She nodded. ‘People always say that views are breathtaking, don’t they? But they should be breath-giving, surely?’ She turned to smile at him. ‘And I don’t just mean the wind.’

For a few minutes they stood side by side in silence, watching the dazzle of spray over the rocks, the unbelievable dark blue of the water. A curlew called above them, the scent of vanilla drifted from a late flowering bush of gorse.

‘I came here for the first time when I was ten,’ said Quin. ‘I bicycled from Bowmont with my hammer and my Boy’s Own Book of Fossils. I started to chip at the rock — and suddenly there it was. An absolutely perfect cycad, as clear and unmistakable as truth itself. That was when I knew I was immortal — that I personally without the slightest doubt would solve the riddle of the universe.’

‘Yes, I know that one. Things that are for you. No doubts, no hesitation.’

‘Music in your case, I suppose,’ he said resignedly, waiting for the ubiquitous Mozart to appear on the horizon, towing Heini in his wake.

‘Yes. The first time I heard the Zillers play. But…’ She shook her head, ‘I loved the Grundlsee. I really loved it, the lake and the berries and the flowers, but when we went there it was still part of the way I’d always lived… with the university and people talking about psychoanalysis and all that. But here… the first morning by the sea… and now, still… I don’t understand what’s happened.’ She looked up at him and he saw the bewilderment on her face. ‘I feel as though I shall be homesick for this place all my life… for the sea… but how can I be? What has it to do with me? It’s Vienna I’m homesick for. I must be.’

His silence lasted so long that she turned her head. It seemed to her that his face had changed — he looked younger, more vulnerable, and when he spoke it was without his usual ease.

‘Ruth, if you wanted it to be different… If —’

He broke off. A shadow had fallen between them and the sun. Tall and looming, Verena Plackett stood there, holding out a piece of rock.

‘I wonder if you could clear up a point for me, Professor,’ she said. ‘I think this must be one of the brachiopods, but I’m not entirely sure.’

Quin did not speak to Ruth again till after their return. He was making his way up the cliff path when he heard footsteps and turned to find her hurrying after him, the puppy in her arms.

‘I’m sorry to bother you, but could you be so kind as to take him up to the house? Pilly would, but she’s busy cooking and I promised Martha I’d see that he got back safely.’

‘Why don’t you take him yourself? You’ve obviously made friends with Martha.’

‘No.’

He remembered her refusal to come to lunch, and meaning to tease her, said: ‘You’ll have to look at the place sometime, you know. After all, if I’m killed before Mr Proudfoot can put us asunder, Bowmont will be yours.’

Her reaction amazed him. She was furious; her face distorted — he almost expected her to stamp her feet.

‘How dare you talk like that! How dare you? Mr Chamberlain said there would be no war, he promised… and even if there is you don’t have to fight in it. It was absolutely unnecessary you going off to the navy like that, everyone said so. You could do much more good doing scientific work. It was ostentatious and stupid and wrong.’

‘Come, I was only joking.’

‘Exactly the sort of jokes one would expect from an Englishman. Jokes about people being dead.’

She thrust the puppy in his arms and stamped away down the hill.

‘As a woman I was unfortunately not able to follow the sport,’ said Verena, who was engaging Lord Rothley in a conversation about pigsticking. ‘But I watched it in India and found it quite fascinating.’

Lord Rothley mumbled something and held out his glass to Turton who, detecting a certain glassiness in his lordship’s eye, filled it to the brim with whisky.

The party was a small one: The Rothleys, the Stanton-Derbys and the widowed Bobo Bainbridge, come to welcome the Placketts and discuss the arrangements for Verena’s dance. Needless to say Verena, who had prepared so assiduously for Sir Harold in the matter of the bony fishes, had gone through the Northumberland Gazette to ascertain the interests of the guests, though in the case of Lord Rothley she had been deceived a little by the small print. It was pig breeding rather than pig sticking that interested his lordship.

Her duty to him completed, Verena moved over to Hugo Stanton-Derby standing with Lady Plackett by the fireplace. The excellent relationship which Verena enjoyed with her mother had enabled them to divide their labours: Verena had repaired to the Encyclopaedia Britannica in the library to read up about Georgian snuff boxes which Stanton-Derby collected, while Lady Plackett immersed herself in the Financial Times for it was as a stockbroker that he earned his living.

The resulting conversation was as informed and intelligent as might have been expected, and when Verena turned to the women, they found her most understanding and sympathetic about their complaints. For as might have been expected, the refugees that Quin had wished on them were continuing to be ungrateful and difficult. Ann Rothley’s dismissed cowman had been taken on by the Northern Opera Company and caused havoc among the servants.

‘They’re all asking for time off to go to Newcastle and hear him sing in that ridiculous opera — the one where they burn a manuscript to keep warm. Something about Bohemians.’

And Helen’s chauffeur too was giving trouble: he was threatening to leave and go to London to try and join a string quartet.

‘Well if he does at least you won’t have to listen to all that chamber music,’ said Frances.

But, of course, it wasn’t so simple — it never is.

‘Actually, he’s rather good at his job,’ said Helen, ‘and much cheaper than an Englishman would be.’

Only with Bobo Bainbridge did Verena not attempt to converse. Bobo, whose adored husband had dropped dead nine months ago and whose mother-in-law did not approve of displays of grief, now navigated through her social engagements by means of liberal doses of Amontillado, and for women who let themselves go in this way, Verena had nothing but contempt.

At nine o’clock, Quin took the men to smoke and play billiards in the library and the women were left to discuss Verena’s party.

This, somewhat to Frances’ dismay, soon grew into a much larger affair than she had intended. Her suggestion of a buffet supper and dancing to the gramophone caused Lady Plackett considerable surprise.

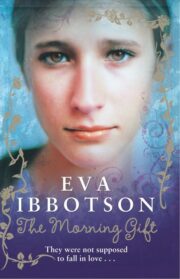

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.