Leonie accepted and asked the old lady for instructions.

‘There are candles,’ said Mrs Weiss positively. ‘That I know. One lights one each day for eight days and they are put in a menorah.’

‘How can that be?’ asked Dr Levy. ‘If there are eight days there are eight candles and a menorah only has seven branches. And there are certainly prayers. My grandmother prayed.’

‘But what did she pray?’ asked Leonie, tilting her blonde head in resolute pursuit of Jewishness.

Dr Levy shrugged and Ziller said that von Hofmann would know. ‘He’ll be here in a minute.’

‘Why should he know? He has no Jewish blood at all,’ said Mrs Weiss dismissively.

‘But he was in that Isaac Bashevis Singer play, don’t you remember? The Nebbich. That’s a very Jewish play,’ said Ziller.

But von Hofmann, when he came, was hazy. ‘I wasn’t on in that act,’ he said, ‘but it’s a very beautiful ceremony. All the actors were very much moved and Steffi bought a menorah afterwards in the flea market. I could ask her — she’s selling stockings in Harrods.’

No one, however, wanted to trouble Steffi who was an exceedingly tiresome woman though a good actress, and Miss Violet and Miss Maud, who had been listening to this exchange, now said that they’d soon have to start thinking about getting their Christmas decorations up.

Leonie brightened, approaching familiar ground.

‘What do you do for Christmas?’ she asked the ladies.

‘Well, we go to evensong,’ said Miss Maud. ‘And we decorate the tea rooms with paper chains and put a sprig of holly on each of the tables.’

‘And the advent rings?’ asked Leonie.

‘We don’t have those,’ said Miss Maud firmly, scenting a whiff of popery.

‘But a little tree with red apples and a sliver star?’

The ladies shook their heads and said they didn’t believe in making a fuss.

‘But this is not a fuss,’ said Leonie. ‘It’s beautiful.’ And shyly: ‘I could make some Lebkuchen… gingerbread, you know… hearts with icing and red ribbon?’

‘Georg has a big fir tree in his garden,’ said Mrs Weiss. ‘I can cut pieces from it in the night when Moira sleeps.’

‘My wife brought her little glockenspiel,’ said the banker unexpectedly. ‘I said to her she is stupid, but she had it from a child.’

Back in the kitchen, Miss Maud and Miss Violet looked at each other.

‘I suppose it won’t hurt,’ said Miss Maud, ‘though I don’t want pine needles all over the place.’

‘Still it’s better than that Hanukkah thing of theirs. I mean, they won’t get very far if they can’t remember how to do it,’ said Miss Violet.

Mrs Burtt wrung out her cloth and hung it over the sink, above which Ruth had pinned a diagram showing The Life History of the Pololo Worm.

‘And it’ll cheer Ruth up to see the place look pretty,’ she said.

Miss Maud frowned, wondering why their waitress should need cheering. ‘She’s very happy since Heini came. She’s always saying so.’

‘But tired,’ said Mrs Burtt.

Three days after Leonie’s failure over the Festival of Light, Ruth called at the post office on her way to college and drew out of her private box a small packet with a red seal which she opened with a fast-beating heart.

Minutes later, she stood in the middle of a crowd of hurrying people, staring down at the dark blue passport with its golden lion, its prancing unicorn and the careless motto: Dieu et Mon Droit.

‘I am a British subject,’ said Ruth aloud, standing on the pavement opposite a greengrocer’s shop and seeing the Secretary of State in a top hat wafting her through foreign lands.

If only she could have shown it to everyone: the naturalization certificate which confirmed her status; the passport she held in her own right! If only she could have marched into the Willow holding it aloft and danced with Mrs Burtt and hugged her parents. People in Europe would have killed for what she held in her hand — yet no one would have grudged her her luck, she knew that.

But, of course, she could show it to no one. It was Ruth Somerville, not Ruth Berger, that His Britannic Majesty wished to pass without let or hindrance anywhere in the world, and the passport would have to go with the rest of her documents to be scuttled over by the recalcitrant mice.

She was early for college. Since Heini came, Ruth had slept with the alarm under her pillow set for 5.30 so that she could do two hours of work while it was still quiet, Now, as she sat in the Underground, she wanted to mark this day; pay some kind of tribute — and on an impulse she left the train three stops before her destination and climbed the steps of the National Gallery to look down at Trafalgar Square.

She was right, this was the heart of her adopted city. The fountains sparkled, the lions smiled… Through the Admiralty Arch opposite she could see the end of The Mall leading to Buckingham Palace where the shy King lived who was being so good about his stammer, and the soft-voiced Queen looked after the princesses on her biscuit tin.

She tilted her head up at Nelson on his column; the little man who was the favourite hero of the British and who had said, ‘Kiss me, Hardy,’ or perhaps, ‘Kismet, Hardy,’ — talking about fate — and then died. He had been so brave… but then they were brave, the British. Their girls felled each other with hockey sticks and never cried; their women, in earlier times, had stridden through jungles in woollen skirts to turn the heathen to the word of God.

And she too would be strong and brave. She would do well in the Christmas exams and stay awake for Heini when he needed to talk late at night. It was ridiculous to think that anyone needed more than four hours’ sleep. She could do it all: her essays, her revision, her work at the Willow and still help Heini with his interpretations.

The Will Has Only To Be Born In Order To Triumph quoted Ruth who had read this motto on a calendar and been much impressed.

It was only now that she gave her mind to the letter which Mr Proudfoot had enclosed and saw that she was bidden to attend his office on the following afternoon.

Proudfoot had thought it simplest to see Ruth personally and had said so to Quin. ‘It would make sense if you came together, but I suppose we can’t be too careful.’

For after naturalization came the next stage — annulment. To facilitate this, a massive document had been prepared, requiring to be signed by both parties in the presence of a Commissioner for Oaths — and involving Dick Proudfoot’s articled clerk in several hours of work. This affidavit was to be submitted to the courts in the hope that it would come before a judge who would accept it as evidence of nullity without demanding further proof. Whether this would in fact happen was anyone’s guess since the procedure involving annulment in foreign-born nationals was under review and things that were under review never, in Mr Proudfoot’s experience, became simpler.

It so happened that Ruth was waiting in the outer office and that he saw her first with her back turned, looking at a small watercolour on the far wall. The sun came at a slant through the window and touched her hair so that it was the golden tresses, the straight back, he saw first — and immediately he steeled himself, waiting for her to turn. Mr Proudfoot was deeply susceptible to women and had once driven his car into a telephone kiosk on the pavement of Great Portland Street because he was watching a girl come out of her dentist and he knew that when girls with rich blonde hair turn round there is disappointment. At best mediocrity, at worst a sharp, discontented nose, a petulant mouth, for God sensibly preserves his bounty.

‘Miss Berger?’

Ruth turned — and Mr Proudfoot felt a surge of gratitude to his Creator. At the same time, his view of Quin as a chivalrous rescuer of unfortunates receded. What surprised him now was Quin’s haste to get rid of a girl most people would have latched on to with a bulldog bite.

‘This is such a nice picture,’ she said when they had shaken hands. ‘It’s so friendly… the way the tree roots curve right down into the water. It was like that where we used to go in the summer, on the Grundlsee.’

‘Yes. It was done in the Lake District; I suppose it’s the same sort of landscape.’

‘Who painted it?’

‘Actually, I did. When I was a student. I used to dabble in watercolours a bit,’ he said, retreating into British modesty.

Ruth did not care for this. ‘It has nothing to do with dabbling,’ she said reproachfully. ‘It’s beautiful. But I suppose now you paint the river and the places round here?’

‘No. As a matter of fact, I haven’t put a brush to paper for years.’

‘Why is that? Because there is so much to do here?’ she said, following him into the office.

‘Well, yes… but I suppose I could find time. One gets discouraged, you know, being an amateur.’

Ruth frowned. ‘I don’t want to be impertinent when you’ve been so helpful about getting me naturalized and now annulled — but I think that’s very wrong. An amateur is someone who loves something. In all the Haydn Quartets there is a part for an amateur — the second violin, usually, or the cello — but it’s just as beautiful.’

But the sight of the document Mr Proudfoot had prepared for her now silenced Ruth as she waded, biting her lip, through its several pages of parchment, its red seal, its Gothic script and the strange words in which she wished the law to know that she had never been laid hands on, or laid hands herself, on Quinton Alexander St John Somerville.

‘I don’t know if this will work, Miss Berger — some judges won’t accept an affidavit without medical evidence and Quin is determined not to put you through anything like that.’ He flushed, unable to pursue the subject.

‘Yes. He is being so kind — so very kind — which is why I must get this annulment through quickly so that he can marry someone else.’

Proudfoot, who had been led to believe that it was Ruth who was in a hurry, looked surprised.

‘Does he want to marry anyone else?’

‘Perhaps not he, but other people. Verena Plackett, for example.’

‘I don’t know who Verena Plackett is, but I assure you that Quinton can look after himself. People have been trying to marry him since he was knee-high to a goat.’ He pulled the formidable paper closer. ‘Now listen, my dear, because this document is unique and it’s complicated and you have to get it right. You must sign it exactly where I’ve pencilled it — there and there and again over the page — with your full name and in the presence of a Commissioner for Oaths. He’ll make a charge and Quin has asked me to give you a five-pound note to cover the cost. Any commissioner will do, there’s sure to be one in Hampstead. When you’ve done it, bring it back to me — I wouldn’t trust the post; if it’s lost we’ll miss the next sitting of the courts and then we’re in trouble. And if there’s anything you don’t understand, just let me know.’

‘I think I understand it,’ said Ruth. ‘Only perhaps you could wrap it in something for me?’ For her straw basket contained, in addition to her dissecting kit and lecture notes, the remains of Pilly’s sandwiches which, now that Heini was eating with them, she took back to Belsize Park rather than feeding to the ducks.

‘Don’t worry — there’s a cardboard tube — it gets rolled up and put inside. I’ll expect you in a few days, then. Take care!’

‘What do you think?’ said Milner, looking at Quin with his head on one side and an ill-concealed glint of excitement in his eyes.

Quin stood looking down at the drawer of fossil-bearing rocks which Milner had pulled open, first unlocking the storage room with rather more formality than usually went on in the Natural History Museum.

‘You’re right, of course. It’s part of a pterosaur. And I’d have sworn it was from Tendaguru. The Germans have got two casts like that in Berlin from the 1908 expedition. I’ve seen them.’

‘Well, it isn’t. Do you know where this was found?’

Quin, tracing out the beaked skull, still partly embedded in the matrix, shook his head. A wing-lizard, immemorially old and very rare.

‘On the other side of the Kulamali Gorge — eight hundred miles away. He showed me the place on the map. Farquarson may be no more than a white hunter, but he’s no liar and he knows Africa like the back of his hand. I’ve written down the exact location.’

Quin laid the bone back in the tray. ‘Are you serious? South of the Rift?’

‘That’s right. He didn’t know how important it was and I didn’t tell him. It’s a bit of luck, him not being a palaeontologist, otherwise we’d have everyone down on us like a ton of bricks. Whereas as it is…’

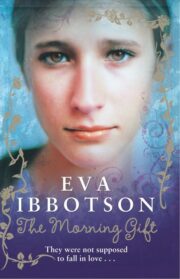

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.