‘Careful!’ said Professor Berger, as he had said every year since Ruth was old enough to light the candles on the tree.

He had travelled overnight on the bus from Manchester and would greatly have preferred to be at home with his family, but now as he looked at the circle of faces and touched his daughter’s head, he was glad they had come together with their friends.

‘I never seen it like that,’ said Mrs Burtt. ‘Not with real candles.’

And Miss Violet and Miss Maud forgot the needles dropping on the floor and the wax dripping on to the tablecloths and even the appalling risk of fire, for it was beyond race or belief or nationality, this incandescent symbol of joy and peace.

Then came the presents. How these people, some of whom could scarcely afford to eat, had found gifts remained a mystery, but no one was forgotten. Dr Levy had discovered a postcard of the bench where Leonie had been overcome by pigeons and made for it a wooden frame. Mrs Burtt received a scroll in which Ruth, in blank verse, proclaimed her as Queen of the Willow. Even the poodle had a present: a bone marrow pudding baked on the disputed cooker at Number 27.

But Heini’s presents were the best. It had occurred to Heini that while he was borrowing money from Dr Friedlander for the competition, he might as well borrow a little extra for Christmas, and the dentist had been perfectly happy to lend it to him. So Heini had bought silk stockings for Leonie and chocolates for Aunt Hilda and a copy of The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius for the Professor who was fond of the Roman Stoic. This had used up more money than he expected and when he went into a flower shop to buy red roses for Ruth, he found the cost of a bunch to be exorbitant. It was the assistant who had suggested a different kind of rose — a Christmas rose, pale-petalled and golden-hearted, and put a single bloom, cradled in moss, into a cellophane box — and now, as he saw Ruth’s face, he knew that nothing could have pleased her more.

After the presents came the food — and here the horsehair purse of Mrs Weiss had turned into a horn of plenty, emitting plates of salami and wafer-thin smoked ham… of almonds and apricots, and a wild white wine from the Wachau for which Leonie had scoured the shops of Soho.

But at eleven, Ruth and Heini slipped out together and walked hand in hand through the damp, misty streets.

‘It was lovely, wasn’t it?’ said Ruth. ‘And you look so elegant!’ On the first day of the holidays, she had returned to the progressively educated children of the lady weaver and used the money she had earned to buy Heini a silk scarf to wear with his evening clothes. ‘But, oh if only it would snow! I miss snow so much — the quietness and the glitter. Do you remember the icicles hanging from the wall lamps in the Hofburg? And the C Minor Mass coming out of the Augustiner chapel, and the bells?’

They had reached the door of Number 27. ‘I’ll play it for you,’ said Heini pulling her into the house. ‘Come on! I’ll play the snow and the choirboys and the bells. I’ll play Christmas in Vienna.’

And he did. He sat down at the Bösendorfer and he made it for her in music as he had promised. He played Leopold Mozart’s ‘Sleigh Ride’ and wove in the carols that the Vienna Choirboys sang: ‘Puer Nobis’ and the rocking lullaby which Mary had sung to her babe… He played the tune the old man had wheezed out on his hurdy-gurdy in the market where the Bergers bought their tree — and then it became Papageno’s song from The Magic Flute which had been Ruth’s Christmas treat since she was eight years old. He played ‘The Skater’s Waltz’ to which she’d whirled round the ice rink in the Prater and moved down to the bass to mime the deep and solemn bells of St Stephan’s summoning the people to midnight mass. And he ended with the piece he had played for her every year on the Steinway in the Felsengasse — ‘their’ tune: Mozart’s consoling and ravishing B Minor Adagio which he had been practising when first they met.

Then he closed the lid of the piano and got to his feet.

‘Ruth,’ he said huskily, ‘I liked your present, but there is only one present I want and need — and I need it desperately.’

‘What?’ said Ruth, and her heart beat so loudly that she thought he must be able to hear.

‘You!’ said Heini. ‘Nothing else. Just you. And soon please, darling. Very soon!’

And Ruth, still caught in the wonder of the music, moved forward into his arms and said, ‘Yes. It’s what I want too. I want it very much.’

Quin’s Christmas Eve was very different.

He had walked since daybreak and now stood on the top of the Cheviots looking across at the rolling slopes of blond grass bent by the wind and the fierce storm clouds gathering above the sea. Tomorrow he would do his duty by his parishioners, read the lesson in church, and accompany his aunt to the Rothleys’ annual party — but this day he had claimed for himself.

Yet when he began to apply his mind to the problem which had brought him up here, he found there was no decision to be made. It had made itself, heaven knew when, in that part of the brain so beloved of Professor Freud.

Instead of thought came images. A steamer to Dar es Salaam… the river boat to Lindi… a few days with the Commissioner to hire porters. And then the long trek across the great game plains on the far side of the Rift. He had dreamt of that journey when he was working in Tanganyika all those years ago — and if Farquarson was telling the truth… if there really was an outcrop of fossil-bearing sandstone in the Kulamali…

As he saw the landscape, so he saw the people he would take. Milner, of course, and Jacobson from the museum’s Geology Department… Alec Younger, back from the East Indies and longing to be off again… Colonel Hillborough who’d had his fill of administration and would harness the resources of the Geographical Society to the trip… And one other person; someone young to whom he’d give a break. One of the third years, perhaps. It would depend on the exam results, but young Sam Marsh was a possibility.

Africa had been his first love: the bone pits of Tendaguru had set him on his way professionally and if this was to be his last journey it would be a fitting end to his travels. There were other advantages in going to Kulamali. The territory was British ruled and from it one could go through other protectorates back to the sea. No danger then, if war came, of being locked up as a foreigner. He’d be able to make his way back home and enlist.

Another decision, seemingly, had already been made in some part of his mind. This was not a journey to be packed into the summer vacation. He was leaving Thameside, and leaving it for good.

Chapter 24

‘I must say sometimes I wish the human heart really was just a thick-walled rubber bulb, don’t you?’ said Ruth to Janet, with whom she had stayed behind to draw a model of the circulatory system kindly constructed for them by Dr Fitzsimmons.

Nearly two months had passed since Christmas, and Heini’s passionate plea that they should be properly together was about to be answered at last. Ruth had not delayed so long on purpose. She wanted to be like the heroine of La Traviata who had sung about living utterly and then dying and she knew that in giving herself to Heini she was serving the cause of music. Heini, who was studying the Dante Sonata for the competition, had become very interested in the composer’s private life and Liszt (who was famous for being demonic) had already been through a number of countesses by the time he was Heini’s age, so that it was entirely understandable that Heini did not feel able to do justice to his compositions while in a state of physical frustration.

All the same, it hadn’t been easy. The opportunities for being demonic at Number 27 were nonexistent and they couldn’t afford a hotel. So she had turned to Janet, who had so completely got over being a vicar’s daughter, and Janet had come up trumps.

‘You can have my flat,’ she had said. ‘We’ll have to find out when the other two are away, but Corinne goes home most weekends and Hilary quite often works all day Saturday; I’ll let you know when it’s safe.’

And the day before, Janet had let her know. The very next Saturday, Ruth could have the whole afternoon to be with Heini. Now, looking at her friend, Janet said: ‘You don’t have to, you know. No one has to. Some people just aren’t any good unless they’re married and it seems to me you may be one of them.’

‘It’s just cowardice,’ said Ruth, rubbing out a capillary tube which was threatening to run off the page. ‘If you can do it, so can I.’

Janet’s reply was a little disconcerting. ‘Yes, I can and I do. Someone started me off when I was sixteen and I was ashamed because my father was a vicar and I wanted to show I wasn’t a prig. And once you start, you go on. But I’m twenty-one and I’m a bit tired of it already and sometimes I wonder what the point of it all is.’

It was as they were packing up their belongings that Ruth, looking sideways at Janet, said: ‘Do you think I ought to read a book about it first?’

‘Good God, Ruth, you do nothing but read books! You must know more about the physiology of the reproductive system than anyone in the world.’

‘I meant… a sort of manual. A “How to do it” one, like you have for mending motorbikes.’

‘You can if you like. If you go to Foyles and go up to the second floor you can read one free. They’ve got half a dozen of them in the Human Biology section. The assistants won’t bother you; they’re used to it.’

So on the following day, Ruth went to Charing Cross in her lunch hour and Pilly insisted on accompanying her. Ruth had not meant to burden Pilly with the ecstatic experience she was about to undergo, but Pilly had been so hurt when Ruth had secret conversations with Janet that she had let her into the secret. Pilly had been very admiring; ‘You are brave,’ she said frequently, but she had taken to bringing along cod-liver oil capsules in her lunch box and urging Ruth to swallow them, and this was not quite the image Ruth had in mind.

‘I won’t come upstairs with you,’ said Pilly. ‘I’m sure I won’t be able to understand the diagrams and there are probably going to be a lot of names. I’ll wait for you in Cookery.’

Pilly was right. There were a lot of names and the diagrams were deeply dispiriting. One would just have to rely on living utterly.

‘It’ll be all right, Ruth,’ said Janet when they got back to college. ‘Honestly. I’ll take you to the flat tomorrow and show you where everything is. There’s just one thing you want to be careful of.’

Ruth swallowed. ‘Getting pregnant, you mean?’

‘No, not that — obviously Heini will see to that. It’s about his socks.’

‘What about them?’ said Ruth, feeling her heart pound at this new threat.

Janet laid a hand on her arm. ‘Try to make sure that he takes them off early on. A man standing there with nothing on and then those dark socks… it can throw you a bit. But after all, you love him. There’s really nothing to worry about at all.’

Janet’s flat was in Bloomsbury, in one of those little streets behind the British Museum. Had she climbed down the fire escape which led from the kitchen, Ruth would have found herself a stone’s throw from the basement where Aunt Hilda worked. Hilda wouldn’t be shocked by what she was about to do. The Mi-Mi were very easy going; everyone in Bechuanaland took love lightly.

But her parents…

Ruth forced her mind away from what her parents would think. She had so hoped that the annulment would be through by now — then she could at least have got engaged to Heini. But it wasn’t and that was her fault and another reason for not keeping him waiting any longer.

The flat was very Bohemian; the furniture was sort of tacked together and there wasn’t much of it and everything was very dusty. Still, that was a good thing. Mimi had been a Bohemian, arriving with her candle and her tiny frozen hands and not fussing any more than the heroine of La Traviata about being married. She had died too, of course, clutching her little muff, but not from sin, from consumption — one had to remember that.

Heini should be here any moment now. She had cleaned the sink and swept the kitchen floor and unwrapped the wine that Janet had brought her as a good luck present. Ruth had been worried about this — Janet was dreadfully hard up — but Janet had waved her protests away.

‘It was a special offer from the Co-op,’ she said.

The wine would be a big help, Ruth was sure of that, remembering what it had done for her on the Orient Express.

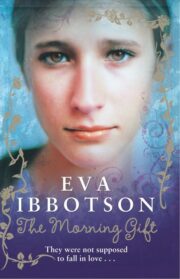

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.