‘He will want supper,’ said Mishak, and was proved right.

It was Ruth who did not want supper. Ruth who phoned to say she would be late… and who was walking the streets wringing her hands like a Victorian heroine. Ruth who felt disgraced and shamed and wished the earth would open up and swallow her…

For after all, it had happened, the thing she had dreaded that night on the Orient Express. It was prophetic, all the reading she had done there on the Grundlsee. They had not minced their words, those behavioural experts with their three-volumed tomes: Havelock Ellis and Krafft-Ebing and a particularly alarming man called Eugene Feuermann. It was not for nothing that they had devoted chapter after chapter to one of the great scourges of those who seek fulfilment in the act of love.

Anything would have been better than what had happened. There were chapters on nymphomania too, but Ruth would have settled for that. Nymphomania might end badly, but it sounded generous and giving. Someone with nymphomania might expect to live utterly and die whereas…

Why me? thought Ruth, when I was so much looking forward to being with him. And what would Janet say? Could one even mention it to Janet who was so bountiful in the backs of motor cars?

The word drummed in her ear — the dreaded word which branded her as ice cold, as having splinters in her heart as if the Snow Queen herself had put them there. It had begun to drizzle and she pulled up the hood of her loden cape, but the bad weather suited her. Why should the sun shine ever again on someone who was the subject of two whole chapters and a set of tables in Feuermann’s Sexual Psychopathology?

Ruth walked for one hour, and two… and then, tainted or not, she made her way to the Underground. Sooner or later she would have to face Heini and to add cowardice to coldness would solve nothing.

‘Come in.’

Fräulein Lutzenholler sat in her dressing-gown drinking a cup of cocoa with a wrinkled skin, which she had made earlier, spilling the milk. Above her hung the portrait of the couch she had used to see patients in Breslau, a small blue flame hissed in the gas fire, and she was not at all pleased to see Ruth.

‘I am going to bed,’ she announced.

Ruth entered, her hair in disarray, her eyelids swollen. ‘I know; I’m sorry. And I know you can’t help me because I can’t pay you and psychoanalysis only works if you pay the person who’s doing it.’

‘And in any case I am not permitted to practise in England,’ said Fräulein Lutzenholler firmly.

‘But I thought you might know if there’s anything I can do.’ It had been difficult to come into the analyst’s uninviting room and after her remarks about the lost papers on the bus, Ruth had sworn never to consult her again, but it seemed one couldn’t escape one’s fate. ‘I am so unhappy, you see, and I thought there might be something I haven’t understood about my childhood. Something I have repressed.’

Fräulein Lutzenholler sighed and put down her cup. ‘Is it true that Heini is moving away?’ she asked.

Ruth nodded, and something that was almost a smile passed over the analyst’s features, lightening the moustache on her upper lip.

‘It is not so simple, repression,’ she said.

‘No. But I know that if you see something awful when you are small… if your parents… you know if you find them making love. But I never did. When Papa had his afternoon rest everyone crept about and my mother sat in the drawing room with her embroidery like a Grenadier Guard shushing everybody. And anyway our flat had double doors, you couldn’t hear anything. And on the Grundlsee I always fell asleep very quickly because of all that fresh air and though the maids told me about Frau Pollack always wanting gherkins before she let her husband come to her, I don’t think it was a trauma and anyway I haven’t repressed it. And I can’t think —’

Fräulein Lutzenholler frowned. The good humour caused by the news that Heini was leaving had evaporated and she was worried about her hot-water bottle. She had filled it half an hour before and liked to get into bed while it was still in peak condition.

‘What are you talking about?’ she said, spooning the cocoa skin into her mouth. ‘I don’t understand you.’

Ruth, who had shied away from the word all day, now pronounced it.

There was a pause. Fräulein Lutzenholler looked at the clock. ‘Ruth, it is a quarter to eleven. I cannot discuss this with you now. It is a technical problem and there can be very many causes; physiological, psychological…’

‘Oh, please… please help me!’

Fräulein Lutzenholler stifled a yawn.

‘Very well, tell me what happened.’

Ruth began to speak. Her words tumbled over each other, tears sprang to her eyes, her hair fell over her face and was roughly pushed away.

To these outpourings of a tortured soul, Fräulein Lutzenholler listened with increasing and evident displeasure. She put her soiled cup back in its saucer. She frowned.

‘Please understand, Ruth, that technical terms are not there as playthings for amateurs. There is nothing I can do to help you and I now wish to go to bed.’

‘Yes… I’m sorry.’

Ruth wiped her eyes and rose to go. She had reached the door when Fräulein Lutzenholler uttered — and in English — a single sentence.

‘Per’aps,’ she said, ‘you do not lof ’im.’

A few days later, Heini announced that after all he would stay. His stint of room hunting had shaken him: rents were exorbitant, there were absurd restrictions on practising and, of course, no one provided food. With the first round of the competition only six weeks away, he owed it to everyone to provide himself with the best conditions for his work. There was also Mantella. Heini’s agent had planned an interview with the press at which Ruth was to be present. If Heini could not altogether forgive her, he was determined not to harbour a grudge and as the spring term moved towards Easter, a kind of truce was established in Belsize Park.

Among Verena’s many excellent qualities could be numbered a thirst for learned gatherings, especially those with receptions afterwards at which, as the daughter of Thameside’s Vice Chancellor, she was invariably introduced to the participants.

Her reason for attending a lecture at the Geophysical Society was, however, rather more personal. The subject — Cretaceous Volcanism — was one which she was certain would interest Quin, and seeing the Professor out of hours was now her main objective.

But when she took her seat in the society’s lecture theatre, Quin was nowhere to be seen. Instead, on her left, was a small, dapper man with a carefully combed moustache and slightly vulgar two-coloured shoes who introduced himself as Dr Brille-Lamartaine, and showed a tendency to remain by her side even when she moved through into the room where drinks and canapés awaited them.

‘An excellent lecture, I think?’ said the little man, who turned out to be a Belgian geologist of some distinction. ‘I expected to see Professor Somerville here, but he is not.’

Verena agreed that he was not, and asked where he had met the Professor.

‘I was with ’im in India. On his last expedition,’ said Brille-Lamartaine, taking a glass of wine from the passing tray but rejecting the canapés, for prawns, in this country, were always a risk. ‘I was instrumental in leading ’im to the caves where we ’ave made our most important finds.’

He sighed, for Milner, that morning, had told him something that distressed him deeply.

‘How interesting,’ said Verena, who was indeed anxious to hear more. ‘Did you enjoy the trip?’

‘Yes, yes. Very much. There were accidents, of course… my spectacles were destroyed… and the provisions were not what I would have expected. But Professor Somerville is a great man… obstinate… he would not listen to many things I told him, but a great man. Because I have been on his expedition, they have made me a Fellow of the Belgian Academy of Sciences. But now he is finished.’

‘Finished? What on earth do you mean?’

‘He takes a woman on his next expedition! A woman to the Kulamali Gorge… one of his students with whom he has fallen in love. I tell you, this is the end. I will not go with him… I know what will happen.’ He took a second glass of wine and mopped his brow, pursued by hideous images. A naked woman with loose, lewd hair crawling into the safari tent… hanging her underwear on the line strung between thorn trees… She would soon hear of his private fortune and make suggestions: Somerville was known to be someone who did not wish to marry. ‘I have great respect for the Professor,’ he said, draining his glass and drawing closer to Verena who was not at all like the Lillith of his imagination… who was in fact very like his maiden aunt in Ghent, ‘but this is the end!’

‘Wait a minute, Dr Brille-Lamartaine, are you sure he is taking one of his students? And a woman?’

The Belgian nodded. ‘I am sure. His assistant told me yesterday — he is completely in the Professor’s confidence. The Professor has fallen in love with a girl in his class who is very high-born and very brilliant. It is a secret because she must not be favoured, but in June he will declare ’imself. I tell you, women must not go on these journeys, it is always a disaster, I hav’ seen it. There is jealousy, there is intrigue… and they wear nothing underneath.’ He drained his glass and wiped his brow once more. ‘You will say nothing, I know,’ he said. ‘Oh, there is Sir Neville Willington — you will excuse me?’

‘Yes,’ said Verena. ‘Yes, indeed.’

She could not wait, now, to be alone. If any confirmation was needed, this was it! Not that she had really doubted Quin, but his continuing silence sometimes confused her. But how could he speak while she was still his student? Only last week a Cambridge professor had been dismissed because of his involvement with an undergraduate: she had been foolish all along imagining that Quin could declare himself at this stage. And she wasn’t even going to demand marriage before they sailed. Marriage would come, of course, when he saw how perfectly they were matched, but she would not make it a condition.

So now for her First and for being even fitter — if that was possible — than she had been before!

Frances usually came down to London only twice a year; in November for her Christmas shopping and in May for the Chelsea Flower Show.

This year, however, the wedding of her goddaughter — the niece of Lydia Barchester who had come to grief when retreating backwards from Their Majesties — brought her to London at the end of March. She came under protest, as the result of fierce bullying by Martha who had decreed that she needed a new dress and, in particular, new shoes.

‘Nonsense,’ said Frances. ‘I bought some shoes for the Godchester christening.’

‘That was twelve years ago,’ said Martha.

Frances detested buying anything for her personal adornment, but if it had to be done then it had to be done at Fortnum’s in Piccadilly. Displeased, she took Martha’s shopping list and headed south with Harris in the Buick. Beside her on the seat was a cardboard box padded with wood shavings and containing a dozen dark brown bulbs which, after some hesitation, she had dug out of her garden on the previous day.

When in London, Frances did not stay with Quin, whose flat she regarded as faintly disreputable and liable to yield French actresses or dancing girls. She dined with him, but she stayed at Brown’s Hotel where nothing ever changed, and sent Harris to his married sister in Peckham.

Her day had been carefully planned, yet when she found Harris waiting the next morning with the car, the instructions she gave him surprised even herself.

‘Take me to Number 27 Belsize Close,’ she said.

Harris raised his eyebrows. ‘That’s Hampstead, isn’t it?’

‘Nearly. It’s off Haverstock Hill.’

Now why? thought Frances, already regretting her impulse. She was seeing Quin that evening — why not give the bulbs to him to pass on to Ruth?

The streets as they drove north became meaner, shabbier, and as Harris stopped to ask the way, they were given instructions by a gesticulating, scarcely comprehensible foreigner in a large black hat.

Number 27 was all that she had feared; a dilapidated lodging house, the door unpainted, the wood sagging in the window frames. A cat foraged in the dustbins; the paving stones were cracked.

‘I won’t be long,’ she told Harris, and made her way up the steps.

Leonie, enjoying the calm of her sitting room, for Heini had gone to see his agent, heard the bell, went downstairs and saw an unknown, gaunt lady in dark purple tweeds, and behind her an unmistakably expensive, though ancient, motor car with a uniformed chauffeur.

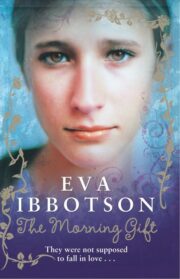

"The Morning Gift" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Morning Gift". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Morning Gift" друзьям в соцсетях.