“Moreau,” provided Whittlesby. Laura looked up at him quizzically. “It’s no good. Fouché is already onto him. They’re simply waiting to give him enough rope to hang himself. Anything more?”

“There was something about a prince, but ink had been spilled across those pages.”

“Ink,” Whittlesby repeated flatly.

“Lots of it.” Laura’s nose wrinkled at the stench of it. In quantity, ink could be a very noxious thing. “Someone had an accident with an inkwell. I was able to make out the word ‘prince,’ but little more.”

“No names?”

“No names,” Laura confirmed. “At least, none that survived the ink spill. If Jaouen knows of any, they’re in his head, not on the page. I saw a copy of the official intelligence report. There was nothing there, either.”

“Either they know and Fouché is reserving the information for his own purposes”—Whittlesby clasped his hands behind his back, pacing to and fro between machines—“or they don’t know. My money is on the latter. Querelle was low on the chain. He wouldn’t be told any more than he needed to know. But if they get Picot or Cadoudal . . .” He came to an abrupt halt in front of Laura. “Keep your eyes open. If you hear anything at all about any further arrests, notify us at once. Employ the usual channels. The code will be . . .”

He paused for a moment to consider.

“A request for Latin texts for Picot, Greek for Cadoudal, and a basic grammar book if the name is one I don’t recognize,” Laura supplied promptly. “If the information is such as to warrant an immediate rendezvous, I’ll ask for a botanical treatise. That is, after all, where carnations are most likely to be found.”

“Excellent!” said Whittlesby, with such approval that Laura found herself in danger of preening like a cat on a sunny windowsill. “I can be found most evenings at the Sign of the Scratching Cat in the Rue de la Huchette. If anything happens.”

He didn’t bother to specify what he meant. Discovery? Danger? Anything encompassed a broad range of possibility.

Laura pursed her lips and gave a very governessy sniff. “I trust I shan’t need to use that information.”

Whittlesby quirked a brow. “I, too. But it doesn’t hurt to be prepared.” He gestured towards the door. “You’d best leave before me. Be sure to look suitably harried and complain about mad poets.”

“I shall do it most sincerely,” said Laura, liking him despite herself. “Until we meet again, Monsieur.”

“Mademoiselle!” Whittlesby’s sleeve fluttered.

“Yes?”

Whittlesby grinned at her. It was a charmingly boyish smile, and Laura could see why the ladies of the First Consul’s court cultivated him, despite his execrable poetry. “Here,” he said, holding out a flat, brown paper-wrapped package. “I nearly forgot to give you this.”

Laura regarded it with some trepidation. “Surely I don’t merit my own copy of your latest volume of poetry?”

“I wouldn’t be so cruel,” said Whittlesby. “You’ll find it contains Aesop’s Fables. In Latin.”

Laura took the parcel from him. “How fortunate I am that the shopkeeper happened to have just the book I was looking for.”

Whittlesby smiled tiredly. “Fortunate, indeed,” he agreed. “Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have some poetry to compose.”

Laura tucked her package neatly under her arm. “And I have children to teach.”

They shared a long look of mutual understanding, two soldiers in the same regiment. It was, Laura thought, rather nice to have comrades-in-arms. It was an experience she hadn’t even realized she had been missing until she had it.

Laura resisted the urge to salute as she left.

When she looked back, the poet was engaged in a vigorous and loud debate with the printer about the type set of his latest volume of poetry, An Ode to the Pulchritudinous Princess of the Azure Toes (and other poems) by the Author of Hypocras’ Feast, an Epic in Thirty-two Parts.

“But I must have the illuminated capitals!” the poet was exclaiming. “How else can I properly demonstrate the celestial fairness of my glowing goddess of podiatric perfection?”

Did he ever worry that he might start to speak that way regularly?

Laura slipped out the shop door, wondering how one maintained that sort of pose so competently for so long. She was a fine one to talk, she realized. It was nothing more than she had done all these years in her role as governess. And yes, one did start to speak that way regularly.

If she were very good and completed this assignment successfully, perhaps the Pink Carnation would let her be something else next time around. But what? Laura’s inner cynic jeered at her. She would make a very unconvincing courtesan.

Still, it would be rather nice to have the chance to try.

Laura contemplated the prospect as she wandered out into the sunlit street. There was a holiday atmosphere about the day, despite the cold. On a Sunday afternoon, the Rue Saint-Honoré was crowded with Parisians making the most of the clear weather before Monday called them again to their respective trades. Above the clatter and chatter, she could hear the faint peal of church bells, so familiar and yet so foreign. Only a few scant years before, those bells had been silent, the churches closed in favor of the deity Reason. With the First Consul setting the tone, the priests were beginning to come back, the churches to attract congregants again, but Sundays were still days of leisure rather than worship: a day to shop, a day to promenade, a day to rest between labors. She was just one among many—another laborer using the day of rest to run errands, shop, and enjoy the sunshine. Everyone was dressed in Sunday finery, a veritable rainbow of bright colors and cheap trimmings, reflecting in a multicolored blur in the plate-glass windows of the shops and cafés that lined the street.

Laura looked in each with interest as she passed. Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun had had her studio not far from here; she wasn’t part of Laura’s parents’ set, but they had taken her there once or twice as a child. She remembered coming with her father and Antoine Daubier to the Café de la Régence to watch them play chess, the two of them finding it a great lark to sit her down at their seats and have her play, first for one, then the other, as the proprietor brought wine for them and macaroons for her.

Some things hadn’t changed. The Café de la Régence was crowded with dedicated chess players. As Laura walked past, the crowd shifted and she caught sight of a man standing just outside, checking his pocket watch. He had left his hat off, and the sun glinted bronze off his short brown hair. He was turned slightly away from her. She could see the cowlick in back, so inappropriately boyish for a member of the Ministry of Police.

The crowd jostled Laura sideways, towards Jaouen. He looked up from his watch. Laura raised her hand in greeting.

“Monsieur Jaouen!” she called breathlessly.

She hadn’t seen him since their run-in in the storage room. His comings and goings had been at odd hours, although she had more than once heard movements in the nursery at night. The first time, she had assumed it was an intruder. Taking up her poker, she had inched open her door and crept out into the schoolroom, only to find Jaouen, still cloaked and spurred, silhouetted in the open nursery door, watching his children sleep. Lowering her weapon, Laura had slipped back into her room, easing the door shut behind her. Some moments weren’t meant to be disturbed.

Jaouen turned at the sound of her voice, squinting into the sun. Already regretting the impulse, Laura did the only thing she could do. She raised her hand in greeting. “Good afternoon, sir—oooph!”

Her greeting turned to a grunt as the man behind her bumped into her, sending her careening forward. She rocketed into her employer, landing with a thump against his chest. Or perhaps that thump was the parcel hitting the ground. Laura didn’t know, because she couldn’t see. Her bonnet was knocked sideways over her eyes, the brim mashed somewhere between her face and Jaouen’s shoulder.

Jaouen’s arms closed around her, his body breaking her fall. The wool of his coat was rough beneath her cheek, warm from the sun and his skin.

Laura heard Jaouen’s voice, somewhere just above her left ear, amused, if rather breathless. “A simple ‘hello’ would have sufficed.”

She could feel the vibration in his chest as he spoke, pressed together as they were through all their layers of fabric. It was the sort of position in which no good governess allowed herself to be put, not even in the street, not even in the middle of the day. It was too intimate, too undignified, too . . . Too.

Laura wriggled. “You can let me go now,” she said in muffled tones.

Jaouen released her to arm’s length, his hands lingering for a moment on her upper arms, steadying her. “A unique way of saying good day, Mademoiselle Griscogne. What do you do for farewell?”

Laura could feel the press of his fingers, even after he let go. “I am so sorry. I didn’t mean to . . . I’m afraid I lost my balance.”

“One often does after being pushed.” Jaouen moved to block her from the bustle of the street, using his only body as a shield. “Think nothing of it. I’m simply glad you fell onto me instead of the window. The patrons of the café might not have been amused to find you as an additional pawn.”

Laura’s bonnet brim stuck up at an odd angle, knocked askew by Jaouen’s shoulder. She tugged at it ineffectually. “It was my own fault for stopping in the middle of the street. I should have known better than to . . . Oh, bother. My parcel!”

“You mean the large, heavy thing that assaulted my foot?” Jaouen leaned over to retrieve the package. It had been wrapped in brown paper, but none too carefully. The string had snapped when the parcel had fallen. “More books, Mademoiselle Griscogne?”

“It would be very difficult to teach without them,” she said quickly, reaching for the volume.

Jaouen held on to it. “Buying volumes for the children on your half day, Mademoiselle Griscogne? I should have thought you would have been set on frivolity.”

“Oh, certainly. I might dip deep into dissipation with a walk around the park, or even a daring visit to a public concert.” Laura made one last attempt to wrench the brim of her bonnet into place. It stubbornly refused to bend. “Since I cannot take the children with me to the bookshop, I must go without them. On my half day.”

“Touché.” Jaouen tipped his hat to her. “A hit.”

Jostled by someone in the crowd, Laura did a little half-step to avoid stumbling into him again. “I would never think of sparring with my employer. It would be decidedly improper.”

Jaouen raised an eyebrow at her. It was amazing how much sarcasm could be packed into one little arc of hair. “If this is your way of being peaceable, I would hate for us to be at war.”

Little did he know. “Would I bite the hand that feeds me?”

“My guess? Yes.” Something in the way he said it made Laura’s cheeks heat. Jaouen cleared his throat, dropping his eyes to the book in his hands. “What’s this, then? What tales are you telling my children?”

Laura resisted the urge to snatch it from his hands as her employer flipped at random through the pages. Each page contained a crude woodcut illustration, with verses in Latin and French beneath.

“These look familiar,” said Jaouen, pausing at the image of a wolf flipping his tail at a cluster of grapes dangling tantalizingly just out of reach. “Aesop’s Fables?”

“It makes an easier introduction to Latin than Caesar’s Wars. The children learn faster when presented with something familiar.”

Jaouen flipped another page. “I wish my Latin master had been half so accommodating.”

Laura craned to see over the edge of the book. It was a crow this time, peering into the water. The Carnation wouldn’t have left anything incriminating between the pages. She hoped. “The nature of the subject matter does not render the instruction any less rigorous, I assure you.”

“I would never suspect you of being anything less than rigorous. I shouldn’t want you to call me out for questioning your pedagogy.”

“Are you afraid I would challenge you to Latin verses at ten paces?”

“It’s the sums at dawn to which I object.”

There was something oddly intimate about the image. Dawn. Disordered hair and tousled sheets, warm skin and dented pillows.

Laura pulled herself together. She was a governess, for heaven’s sake. She wasn’t supposed to think of such things. “The fables do provide excellent moral lessons.”

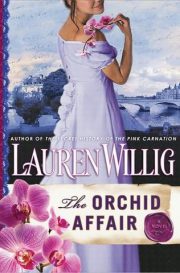

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.