Laura settled for the simple version. “Monsieur Jaouen needed a governess. I am one. It is simple enough.”

Simple enough on the face of it, but Daubier didn’t look reassured. “Was there no one who would take you in, when it happened?”

“When they died, you mean?”

Daubier looked a bit nonplussed by her frankness, but he soldiered boldly on. “Yes. There must have been someone, even abroad. Where were you when it happened?”

“Italy,” Laura lied calmly. “They died in a sailing accident.”

It had been England, but who was there to contradict her now? What did it matter whether it had been Cornwall or Lake Como?

“But surely,” persisted Daubier, “one of their friends . . . Your parents had so many friends.”

Laura couldn’t argue with that. All across Europe, there was hardly a town where there hadn’t been an open door, a spare room, an extra place laid at the table. Her parents had possessed the gift of making themselves loved, not deeply, but broadly. When they had died, they had left behind them a million acquaintances, but no family, no close friends, no one to whom she could reasonably turn for shelter.

To be fair, she hadn’t tried. She hadn’t wanted to be a charity case, Chiaretta and Michel’s useless daughter, without the talent to be trained as an artist, too plain to be anyone’s muse.

Over the years before their death, she had become something of a running project among her parents’ friends. Her parents had sent her for drawing lessons to Daubier, for voice to Aurelia Fiorila, for drama, for dance, for anything at which she might conceivably be found to excel. Laura had become proficient at everything, but excelled at nothing. She had known, as children do without being told, that her parents would have preferred a few spectacular failures to her own particular brand of passionless mastery.

“You might,” said Daubier tentatively, “have come to me.”

He looked so uneasy at making the offer, as though still fearing that she might, after all these years, actually take him up on it, that Laura couldn’t help but laugh.

“Nonsense, Monsieur Daubier,” Laura said fondly. “You would have used me as a perch for your birds and I would have resented you horribly for it.”

“Your parents—,” he began again.

“Loved you dearly,” said Laura firmly. “But you are too old to find yourself with child, and I am far too old to find myself with parent. Consider yourself absolved of all responsibility.”

Daubier let out a little huff of breath. “I always told Chiaretta she ought to have named you Minerva rather than Laura.”

“For my wisdom?”

“No,” said Daubier, “for your domineering disposition.”

Laura wasn’t sure whether to be amused or offended. She had lived so long among strangers that she had forgotten what it was to be among old acquaintances, particularly old acquaintances who had known one since a little beyond birth and claimed all the outspokenness that was the privilege of age.

Perhaps it was true; she might have been accounted a bit assertive as an adolescent.

All right. She had been called domineering more than once. And officious. And occasionally headstrong. But someone had to make sure the bills were paid and the sculptures delivered on time and that her mother’s many admirers didn’t run into one another and cause scenes in the public rooms of inns. Her mother thrived on those scenes, but Laura didn’t. High drama they might provide, but they invariably occasioned a search for new lodging. Hostelries with clean sheets and good soap were hard to find, especially when one had been banned from the bulk of them.

She had raged all these years about being abandoned, but the abandonment had suited her better than an adoption, especially an unwilling one.

Daubier broke into her recollections. “Let me find you another situation,” he said abruptly.

Laura looked at him in confusion. “Another situation?”

“I can find you a post in another household. There are still plenty of affluent families in Paris. Many of them come to me for portraits. If you must earn your living, I can find you a nice family, a pleasant family.”

Laura squinted against the sunshine, wishing she could see more clearly. “Are you saying that Monsieur Jaouen is not?” she asked, half joking.

Daubier’s rumpled face was entirely serious. “I love André as a brother. Well, as a sort of nephew. Or maybe a first cousin once removed. But I should not want to see a daughter of mine in that house.”

Daubier had never had daughters, partly because he had never been able to pull himself away from his canvases long enough to sire any.

“Why ever not?” demanded Laura. “Does Monsieur Jaouen turn into an ogre at the full moon? Hold wild orgies in the basement? Ought I to be on the lookout for headless wives bundled into a trunk?”

Daubier was not amused. “It isn’t that,” he said reluctantly. “André is a man of perfectly sound moral character and respectable habits. But . . .”

Laura’s levity faded away as she watched the old artist poke at the cobbles with the tip of his cane. “You are serious, aren’t you? Why?”

Daubier’s eyes shifted from one side to the other. Lowering his voice, he said tersely, “It isn’t safe to be so closely associated with Fouché’s chosen successor. These are unsettled times.”

“Are you referring to Monsieur Delaroche?”

Daubier glanced anxiously over his shoulder, as though expecting Delaroche to pop up behind them like a genie from a bottle. “Among others. You don’t want to draw their attention to yourself, and you will if you remain with Jaouen.”

“But you are associated with him yourself,” Laura pointed out. “You play chess with him, you call him friend. Why should I be any more in danger than you?”

“I don’t live under his roof.”

“You are very kind, Monsieur Daubier, and I appreciate your concern, but—”

“I’m a meddling old man and you don’t believe a word I say.”

“I would never put it like that.”

“Even if it is true,” he finished for her.

They paused at the gate of the Hôtel de Bac. As always, Jean was nowhere to be seen.

“Tell me about Monsieur Jaouen,” Laura demanded.

“What about him?” Daubier’s eyebrows rose like caterpillars on a string.

Laura couldn’t find a way to put it into words, so she settled for, “Anything you think I ought to know.”

Daubier cleared his throat with a series of harrumphing noises. When the aural symphony died down, he said, “I was better acquainted with his wife. Julie.”

Not surprising. Monsieur Daubier had always made it a practice to be better acquainted with the wives. Even as a ten-year-old, Laura had been aware of that. But then, growing up as she had, she had been an unusually precocious ten-year-old.

“Julie was a pupil of mine, you see,” said Daubier, as if guessing what Laura was thinking.

Of course, she was. Why hadn’t Laura put two and two together? Naturally the most talented young lady of her generation would go to the most acclaimed artist of his.

“You remained friends with Monsieur Jaouen after Madame Jaouen’s death?” Laura prompted.

Daubier assumed his most cherubic expression. “Jaouen plays a good game of chess. A competent chess partner is hard to find, even in Paris.”

For all his practiced bonhomie, Daubier could be infuriatingly close-lipped when he wanted to be. Laura supposed he had to be, with all the secrets that came out over long portrait sittings, but she could hardly count it a virtue when she was the one questioning rather than concealing.

Daubier forestalled further questions by taking her hands into his, as he had long ago with the small child she had been when he had helped her up onto the plinth for her portrait. Even though she was a great deal older now, the gesture made Laura feel small again—small and cherished.

“If you change your mind, you know where to find me.”

Laura smiled up at Daubier, feeling the sun glint against the tips of her eyelashes. Looking into his lined old face, as wrinkled and red as an apple, she felt a surge of affection for him, for all the memories she had all but forgotten and for his clumsy attempt at reparations now.

It was nice to have someone who might be just a little bit on one’s side.

“You’re not still in the old studio, are you?” There it was again, memory, coming back after all this time: sunlight slanting across a honey-colored floor, a green velvet drape cloth nubby to the touch, the prickle of tiny claws against her fingers.

“Yes, in the Place Royale. Having found a place I liked, I saw no reason to leave it.”

Laura marveled at the wonderful sameness of it all. It was nice to know that some things remained the same, and that, come what may, through riot, revolution, and assorted new regimes, M. Antoine Daubier could still be found with brush in hand in the third-floor apartment in the southeast corner of the Place Royale.

Then Daubier ruined it all by saying, with a squeeze of her hands, “Do be careful, my dear. For your parents’ sake.” He reached up a hand to tap her cheek. “And for your own.”

“Oy!” a surly Jean poked his nose through the bars of the gate, reluctantly executing his office as gatekeeper. “It’s you, is it?”

Jean spat into the gravel. Laura recognized this as his hello, how are you? spit.

“Good evening, Jean,” she said, extracting her hands from Daubier’s grasp. So much for emotional reunions. “Would you care to open the gate for me?”

The early dark of winter was beginning to fall, slanting across the building to cast a shadow across the court, so that while the street outside the gate was still in full sun, the courtyard brooded in shadow.

A bird perched above the porte cochere, rooting with its beak among its feathers. Its feathers were a deep, unrelieved black.

Naturally. It would be a raven.

Jean made a great production of hauling open the huge iron doors. “He coming in too?” he demanded, launching another wad of phlegm at Daubier. His supply seemed to be inexhaustible. Laura wondered that the First Consul didn’t deploy him against the Austrians. That would be one way to damp their cannon.

“No, no.” Daubier took a step back, lifting his hands in negation. The raven shifted restlessly on the roof, eyeing the shiny top of Daubier’s cane.

“Will you be all right?” said Laura, thinking of the old man alone, on foot, in the dark. “Perhaps you should take the carriage?”

“No need,” said Daubier. “These old legs can still bear me up. But . . .”

He broke off as Jean slammed the gate between them, metal hitting metal with an ominous clang. Daubier drew in a sharp breath through his nose. Coming straight up to the gate, he rested his hands on the ornate grille, his nose sticking through a particularly swirly curlicue. It ought to have looked comic, but the worry in his eyes killed any appearance of comedy.

“Take care,” Daubier said somberly. “Take care. And remember. If you need me, you know where to find me.”

Overhead, the raven cawed.

Chapter 12

“You should be more careful of the company you keep, Jaouen.”

Despite the sunlight falling through the window, Delaroche managed to keep to the shadows in his side of the carriage. It was almost as though the dark recognized a kindred soul and knit itself around him.

André stretched his legs comfortably in front of him and managed a credible yawn. “Governesses, you mean?” he said. “Surely I could hardly do better than to follow your example.”

Delaroche’s eyes glinted like a rat’s. “Sometimes even the teacher can be taught.”

Not this teacher. André would have laughed if it hadn’t been so important to keep Delaroche on a short string. He would have been more likely to suspect his governess of subversion had Delaroche not gone to such pains to make him do so. If the governess were really Delaroche’s creature, the man would be a fool to draw attention to it. He was just trying to sow discord and dissension, as usual. It was what he did.

Delaroche was slipping, thought André critically. This really wasn’t up to his usual standard.

Of course, it could all be a clever double-fake—if Delaroche were that clever. But Delaroche wasn’t that clever, and his governess wasn’t that malleable. Judging from their prior interactions, André would have been willing to attest that Mlle. Griscogne was about as ripe for subversion as a balky mule.

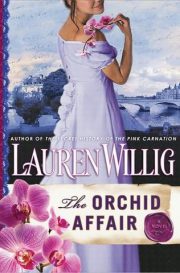

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.