On impulse, André asked, “Did you have a Christian name, in this past life of yours?”

Mlle. Griscogne bent down to pick up a cavalry horse, the mane missing. “A name, but not a very Christian one. They called me Laura.”

“After Petrarch’s muse?” It made sense for one poet to nod to another.

Mlle. Griscogne bedded the horse down among its fellows. “They were thinking more of the laurel crown,” she said wryly. “The coronet of victors and the artist’s reward. I think they hoped it would encourage me to garner laurels.” She busied herself sorting soldiers. “They were disappointed.”

“Julie gave Gabrielle a paintbrush before she could talk.” André wasn’t sure where the words had come from, they just came out.

“What happened?”

“She chewed it,” said André dryly.

He surprised a laugh out of her, a proper laugh. André found himself laughing with her, although at the time it had been anything but comical. He wasn’t quite sure what Julie had expected from a teething child, but she had taken it as a personal affront.

“Monsieur Daubier was always terribly kind about my daubs,” Mlle. Griscogne said reminiscently. “But I could tell he was thinking, Poor girl, her paintings will never hang in the Royal Academy.”

André chuckled, as he was meant to, but he wondered about the little girl she had been. “Did you want them to?”

The question seemed to catch her off guard. “No,” she said, after a moment. “Having grown up with two artists, I’m not sure I would want to be one. It isn’t a very orderly life.”

That was one way of putting it.

He looked around the schoolroom, all the books in their places, all the toys in order. The only thing out of place was the scarlet volume of poetry, a relic from another time and place: her childhood, his youth.

“Once a month, I hold a salon of sorts,” André said abruptly. “It’s nothing terribly formal, mostly artists of various sorts. Painters and poets and writers.”

“How nice,” she said politely.

André clasped his hands behind his back. “It all started when Ju—when my wife was alive. I’ve kept it up since, more out of habit than anything else.”

Mlle. Griscogne was all that was professional. “Would you like the children to come down and recite? I’ve been teaching them excerpts from Racine and Corneille. Gabrielle does a lovely job with the Count’s speech from Le Cid.”

“No!” André said quickly. That was all he needed, to draw more attention to the presence of his children. “No. It wouldn’t be appropriate. My guests are not always the most . . . circumspect of people.”

“You mean they drink and curse,” said Mlle. Griscogne calmly. Her matter-of-fact manner made an odd contrast with her demure façade. But then, she had grown up with Chiara di Veneti.

“They also recite love poetry.” André nodded towards the red book on the table. “Instructive for the children, but not for a few more years, I think.”

“If you want me to make sure they stay out of the way, that can be easily arranged,” she said. “The house is certainly large enough to keep them well out of your way.”

He was making a muddle of this. “No, no,” he said abstractedly. “Jeannette can manage that.”

Mlle. Griscogne looked at him quizzically. “Then . . . do you need assistance with the refreshments?”

André took a deep breath, feeling like a green boy asking a girl into a garden. Absurd, since there was no garden. And Mlle. Griscogne was certainly no girl. There was no need to make a to-do about a simple invitation.

“What I meant to ask was whether you would like to come. To attend. As a guest.”

She looked genuinely confused. “You’re inviting me? To attend?”

“That generally is what ‘guest’ means.” André retreated towards the nursery, speaking rapidly. “The invitation is there, should you choose to accept it. It certainly isn’t a requirement of your job. I thought Daubier might be glad of a chance to see you, that’s all. And you might find other acquaintances of your parents there.”

Stopping abruptly at the door of the nursery, André shrugged. “I leave it to you. It’s your decision whether you want to attend or not.”

He reached for the handle of the door. From the sputtering noises inside, Jeannette was rubbing down Pierre-André’s face, cleaning off the day’s accumulation of dust, jam, and anything else that might reasonably or unreasonably adhere to the face of an active five-year-old boy.

Mlle. Griscogne’s voice arrested him just as he put his hand to the handle.

“It’s very kind of you,” she said. “But you needn’t do this just because my father was the foremost sculptor of his generation.”

André looked at her for a long moment, at the woman who used to be the girl with the finch.

“I’m not doing it for him,” he said, and went to join his children.

Chapter 14

Before joining Serena for drinks, Colin and I went for a stroll along the Seine.

At some point over the course of the afternoon, the sky had cleared. As if repenting of its earlier behavior, it was treating us to a truly spectacular sunset. The spires of Notre-Dame floated in the water of the Seine against a backdrop of red and purple as fantastical as anything from an artist’s absinthe-flavored imagination.

Strolling beside Colin, handsome in his dark blue sport coat and flannels, I felt like something out of an old Audrey Hepburn movie.

I winced as my inadequately shod foot landed in a puddle. All right, scrap the Hepburn bit. One could put on the black cocktail dress, but the whole grace and charm thing was harder. And a puddle was still a puddle. The rain might have cleared, but the ground hadn’t. My open-toed heels kept slipping and sliding on the cracked and damp stone of the street.

We were meeting Serena at a café in the Place des Vosges, only a few yards from the gallery where Colin’s mother’s party was being held, but in the meantime we were both content just to walk, breathing in the cool, fresh air of a March evening after rain. Across the way, the long façade of the Louvre glowed golden in the setting sun, and next to it, the empty space where the Tuileries Palace had once been. Somewhere on the far bank, to the right of the palaces, set farther back from the river, was the house that had once been the Hôtel de Bac, where Laura Griscogne had played her dangerous game of infiltration. I wondered whether it was still there now, turned into a museum like the Cognacq-Jay or broken into flats and offices. Or, perhaps, like the Tuileries or the Abbey Prison, gone altogether now, leaving not even a blue plaque behind to mark its passing. Look on, ye mighty, and despair?

“Crap!” I’d lost the end of my pashmina again. So much for deep thoughts. I lurched for it, hoping to catch it before it trailed its way into a puddle.

Colin, more efficient than I, scooped up the errant end and tucked it up for me, anchoring it under his arm.

“Thanks,” I said.

“All part of the service.”

I looked over at my boyfriend, who was watching the boats go by on the water, and felt a deep surge of gratitude that we were where we were, with all the afternoon’s accidents and alarums behind us. “I’m sorry to have been such a brat earlier.”

“I wouldn’t have said you were a brat.”

Nice save, there. Brat was an Americanism. “Shrew, virago, harpy . . .”

“I should have checked the reservation.” We were still in the warm and gooey make-up stage, where everyone is guiltier-than-thou and a bit of self-flagellation is par for the course. “It never occurred to me that they would put Serena in with us.”

“And especially in that room!” I chimed in.

“I’ve grown rather fond of it,” said Colin blandly, and my cheeks went pink. We’d had a very nice little make-up session there before changing for the party. Not to mention while changing for the party.

Not appropriate thoughts with just an hour to go before meeting his family.

“Well, anyway, I’m sorry for being cranky at you. I’m just a little”—I sketched a gesture in the air—“I don’t know.”

Colin’s lips twisted in a wry expression. “So am I,” he agreed. “Just a little.”

“Are you . . .” I had no idea what I was trying to ask. “Nervous?”

When it came down to it, I didn’t have much of an idea of how Colin felt about his mother and stepfather. We’d skirted around the topic, when circumstances had made it impossible to ignore, but Colin had deflected any attempt to extract anything resembling emotion. All I knew were the bare bones of the situation, not how Colin felt about it.

I got the impression that all wasn’t exactly warm and cozy, but not because Colin had ever precisely said so. It was the little comments; the twist of the lips, the unguarded expression—all such ephemeral things, like the play of light on water, there one minute, gone the next. If I asked him about his family, Colin clammed up. It was only when I didn’t ask that he volunteered.

It was like playing that child’s game—red light, green light, one, two three—creeping and freezing, sent back to the starting line if you tried to move too fast.

This time, I could practically see the light flip to red. “These art dos always make me nervous,” said Colin lightly. “I’m afraid I’ll spill champagne on a Klimt. Look—have you seen the booksellers?”

Accepting the tacit change of topic, I let him draw me in his wake to the kiosks lined up along the side of the walkway, the green metal booths bolted into the stone walls. If he didn’t want to talk about it, I wasn’t going to force him.

If, however, after several drinks, he chose to make his feelings known, that was another matter entirely.

But what if, contrary to everything I’d been taught in every after-school special, talking about things didn’t make them better? What if it only made them harder? There was something to be said for the stiff-upper-lip model. By discussing something, one made it real, gave it—in the words of Shakespeare—a local habitation and a name. There was no ignoring it after that. Maybe it was better for both of us to let Colin display to me the person he wanted to be, not the person circumstance forced upon him.

“May I ’elp you?” The stallholder eyed us suspiciously, as though suspecting us of having untoward designs on the merchandise.

I put down the book I was holding, though not before sneaking a quick glimpse at the price tag. Eek. This was an antiquarian bookseller, not a junk shop, and the extra zeros reflected that.

“Did you see this?” asked Colin, undaunted by the bookseller’s glare or the price tags. He held up a small book with torn paisley paper covers. It was an edition of Ronsard’s poems, a very old edition judging by the bindings.

“Mmm,” I said, scanning the rows. Old books exert a strange fascination for me—their smell, their feel, their history; wondering who might have owned them, how they lived, what they felt. I spotted several early editions of Dumas and Hugo, as well as authors I had never heard of before. They were fairly bulky things, those nineteenth-century tomes, most in several-volume sets.

There were some smaller books among them. I reached for one at random, pulling it out. It was a slim volume, the red leather cover worn in places, the pages yellowed and spotted with age. The gold lettering on the cover had flaked away, making it impossible to read.

I flipped to the title page.

Venus’ Feast. Chiara di Veneti. Chansons d’Amor.

A chill went down my spine. That was—well, too much of a coincidence. Chiara di Veneti had been, by modern academic standards, a minor poet of the eighteenth century. She had also been the mother of Laura Grey, the Silver Orchid.

I wouldn’t have heard of her but for my research on the Selwick spy school, which led me to Miss Grey, aka Laure Griscogne. She wasn’t the sort generally included in AP French exams, partly due to the extreme raciness of some of her subject matter. Admittedly, it had been a racy era, but di Veneti put the author of Dangerous Liaisons to shame.

It boggled my mind that she had been the mother of prim and proper Miss Grey, described by Lady Henrietta Selwick as “a forbidding, gray-toned thing who played the piano as though she were solving a mathematical equation, all logic and no passion.”

I thought of Colin’s mother and the pictures I had seen of her. A free spirit, Colin’s great-aunt had called her, and not in a complimentary way. I looked at Colin, solid and dependable beside me, having assumed his parents’ cares as well as his own. He kept an eye on his sister, looked after his aunt, made sure the family home wasn’t run into the ground. At the same time, I certainly wouldn’t call him all logic and no passion. The four walls of Room 403 could definitely attest to that.

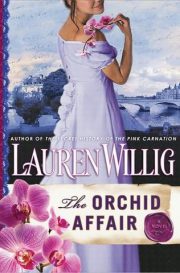

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.