This floor, however, was quite definitely the museum. Yellowing, typed card? Check. Wax mannequin in musty uniform? Check. It was spread out across one broad floor rather than upstairs and downstairs on narrower ones, but otherwise it was just what I had expected. There were panoramic maps of Paris, old city ordinances, a smattering of weaponry. I strolled through the exhibits, past the seventeenth-century and the Affair of the Poisons towards the Revolution and my people.

Tucked away in a corner, I found Georges Cadoudal. There was a print of him, a round-faced man with an open shirt collar. He looked like what my brother would have called “jolly.” He didn’t seem like the sort to keep the entire Ministry of Police hopping. Which just went to show you couldn’t judge anyone by his cover. Notices calling for the arrest of the various conspirators had been framed and posted on the walls. I saw one for André Jaouen, describing him as of medium height, with brown hair and glasses.

There were ledgers, too, immured under glass in the display cases that ran at waist height along the walls, one open to the page where Cadoudal’s description had been entered upon his arrest. Cadoudal had been arrested in March, after a rather spectacular chase scene, detailed in the typewritten card next to his photo. There was no corresponding entry for Jaouen.

This was all very interesting, but I needed the documents that weren’t kept under glass, the other ledgers, warrants, and reports. I made my way back to the front of the museum, where the man at the information desk obligingly led me back into the archives, gestured me to a chair, and, after nobly not snickering at my awful French—well, not too loudly—brought me a large box with the items I had requested.

It was all there. The official bulletins sent by the Prefecture of Police to the First Consul, André’s private reports to Fouché, Gaston Delaroche’s half-mad mutterings. The man was exceptionally fond of memos. Some of them looked as though they had been crumpled and flung against a wall upon receipt. But Fouché wouldn’t do a thing like that, would he?

I found the transcript of the questioning of Querelle, the crucial pages blurred by a spill of ink. Jaouen’s report on the matter followed, written in a crisp, clean hand.

I was amused to note that there was mention of a governess in the official papers following Jaouen’s disappearance, but only as a potential witness to be brought in for questioning. They had never figured it out, not any of them. Ten points to the Pink Carnation.

I worked my way through the disordered pile of material, taking notes in pencil in the notebook I keep for the days I’m too lazy to carry a laptop, or archives that won’t allow electronics. It was fascinating to see the false trails Jaouen had planted, the misleading reports he had written up for his supposed superiors and, later, the elements of the search for him, set out in painstaking detail, reported by Delaroche to Fouché and Fouché to Bonaparte himself.

Laura was right; the capture of Cadoudal had diverted everyone’s attention but that of Delaroche. That man sure knew how to hold a grudge.

The official reaction to Delaroche’s capture appeared to be something along the lines of “Good riddance to bad rubbish.”

I jerked around as the archivist tapped me on the shoulder. Uh-oh. Had I been drooling on the documents? Talking to myself?

Apparently not. The archivist, looking rather amused, murmured that my boyfriend was waiting for me.

He was? I checked my watch. Wow. Somehow, six hours had passed. I became vaguely aware that my shoulders felt sore and I had the sort of dull headache that’s the caffeine addict’s warning that too much time has passed between coffees. Mmm, coffee. And maybe some pain au chocolat. My stomach reminded me that I hadn’t fed it for a while either. Man cannot live on documents alone.

I murmured my thanks to the archivist, gathered up my notebooks, relinquished my ledgers, and wandered, stiff-legged, into the museum to find my boyfriend. I tracked him down in the back room, in front of a collection of miscellaneous implements of destruction, including an early attempt to create a multi-barreled gun. He was studying that last with a great deal of interest when I approached.

“Good research session?” he asked.

“Mmm-hmm.” I yawned, rubbing my eyes. “I feel like I’ve been sleeping for two hundred years.”

Colin assessed me with an experienced eye. “You need coffee, don’t you?”

“Please? I promise I’ll be human once you caffeinate me.”

He could have made snide comments about not making promises I couldn’t keep, but instead he held out a paper bag to me, one of the narrow ones that more resembles an envelope than a shopping bag. “Here. I got this for you. We’ll see if this keeps you occupied until I can get some caffeine into you.”

I drew out his gift as we walked. Despite being paperbacked, it was pretty heavy, the pages thick and glossy. It was an exhibition catalogue from the special exhibit at the Cognacq-Jay, featuring the paintings of Julie Beniet and Marguerite Gérard. Unlike the exhibit, this version contained full biographical details on both women, with a great deal of text.

I accompanied Colin blindly down the stairs, making my way down by chance and luck and the occasional hand on my elbow. About halfway through, I found the portrait of André Jaouen, with two full pages of text going through his career in the National Assembly and his subsequent employment at the Prefecture. It got more perfunctory as it went on, which made sense; the curator’s interest had been in Beniet and the circumstances surrounding this specific painting, not what had happened to Jaouen after her death.

Nonetheless, in the interest of thoroughness, there were a few terse sentences stating that after being implicated in the Cadoudal affair of 1804, Jaouen had relocated to England, where he had remarried, the daughter of the artist Michel de Griscogne and the poetess Chiara de Veneti.

Poor Laura. Even in death she was still Michel and Chiara de Griscogne’s little girl. From an art historian’s view, however, that was the interesting thing about her. There was even a little round illustration set into the bottom of the page showing one of her father’s sculptures, now in the Bode-Museum in Berlin.

Jaouen and his second wife had moved in 1805 to America, where they remained until Jaouen’s death in 1838. Taking advantage of the French-speaking community in New Orleans, Jaouen established a law practice there and eventually became a Louisiana state court judge.

On the facing page, the curator had placed the drawing of a cherubic-looking Gabrielle and the infant Pierre-André. The baby in the picture, Pierre-André Jaouen, the editor pompously informed us, had gone on to become one of the leading naturalists of his day, known for his fine botanical drawings of the foliage of the American South. A colleague of Audubon, they had collaborated on several projects.

Hadn’t there been rumors at one point that Audubon was really the lost Dauphin?

I filed that away for later speculation and went on reading. Gabrielle Jaouen had gone on to become a noted diarist, an advocate for the abolition of slavery and, very late in life, a noisy proponent of the rights of women. She had died in her home in New York in 1893 at the age of ninety-five, leaving behind five husbands, twenty-odd great-grandchildren, and a vast pile of tracts and memoirs.

I wondered what Laura had thought of it all and whether she and Jaouen had had any children of their own. There were fairly easy ways to find out—including tracking down the memoirs of Gabrielle Jaouen de Montfort Adams Morris Belmont van Antwerp—but it was well out of the purview of my current research.

I came up for air about a block from the Prefecture, on the doorstep of a small patisserie. “Thanks,” I said, rubbing my eyes at the transition from the shiny page to less shiny reality. “This is perfect.”

“The book or the café?”

I could smell coffee in the air. There was a long glass case in front of me, displaying an impressive array of pastries, including—yes!—three large marzipan pigs.

“Both,” I said, closing the book and stuffing it into my bag, along with my notebooks, my travel umbrella, a bottle of extra-strength Tylenol, and a plastic thing of tissues that had exploded their plastic. “Did you go back to the Cognacq-Jay?”

Colin signaled to the waitress, who detached herself from her conversation at the back of the bar. “Deux café crèmes,” he instructed.

“Et deux cochons!” I chimed in. I pointed at the glass. “Ceux-là? Les cochons de marzipan? Merci.”

Colin gave me a squeeze. “You found your pigs.”

“One is for you,” I generously informed him. “What did you do today?”

Did you speak to your sister? I wanted to ask, but didn’t. Did you call your solicitor? Did you hire a hit man to take care of your stepfather and/or Mike Rock, aka Micah Stone?

“This and that,” said Colin. We settled ourselves at a rickety table towards the back of the restaurant. “The film crew is scheduled for next month. Fancy coming to stay?”

“As your buffer zone?”

“As my interpreter. Your friend Melinda will be with them.”

“Classmate,” I corrected. A blackboard behind us advertised a dinner prix fixe. It looked rather good. My stomach rumbled again. I smiled gratefully as the waitress put our coffees and a plate with two marzipan-covered pigs down in front of us. “What about Serena?”

Colin’s expression didn’t change. “She won’t be there.”

There was something in the way he said it that effectively cut off future questions. I inched one of the pigs closer to me, idly breaking off its curly marzipan tail, turning it into a little blob of marzipan goo between my fingers.

As much as I hated to admit it, I couldn’t entirely blame Serena for what she had done. It wasn’t just the lure of a partnership in the gallery—that bit I still found vaguely scuzzy. What I could sympathize with was her need to emancipate herself from the protective affection of her one-and-only sibling. It was sweet, but it was also limiting. The way she had chosen was a crummy way to go about bit, but these things are never pretty. Anyone who has ever faced off against a parent knows that.

Serena wanted to live her own life? She had my blessing. But in doing so, she had hurt Colin. She wasn’t my concern; he was. He needed cheering up.

“Look at it this way,” I said encouragingly, leaning my elbows on the table. “Having the film crews there could be kind of entertaining.”

“Like a pleasant interlude on the rack,” said Colin glumly.

“Can I get a side of thumbscrews with that?” Okay, so it wasn’t much of a smile, but I still got a smile. I took a big gulp of my coffee. “View it more as your own personal slapstick comedy opportunity. Shakespeare? To rap music? It’s bound to be absurd. And you can make them pay through the nose if they damage anything.”

Colin perked up at that. “They will, won’t they? I’m not letting them into the library, though.”

I made a fake laughing noise—part chortle, part evil chuckle. “Don’t worry. I’ll see to that.” Micah Stone and his crew were getting anywhere near those manuscripts over my dead body. They were mine, all mine.

Well, maybe not exactly mine, but I was the one with the use of them at the moment.

Colin lifted his coffee cup to me. “All for one?”

I clinked my cup against his, sloshing foam. “And one for all.”

One for both? There were only two of us, after all. Two. As my childhood Sesame Street record had informed me, it was a much better number than one.

What would have happened if Colin hadn’t had a girlfriend with him this weekend, or any girlfriend at all? I didn’t like to think of how alone he would have been. I supposed he did still have his great-aunt, but that wasn’t the same. In multiple ways.

“I nearly forgot.” Colin drew something out of the pocket of his Barbour jacket. It was one of those incredibly deep pockets, designed to hold ammunition and small animal carcasses. Or, in this case, a slim, red-bound book. “We forgot this at the gallery last night.”

The cover looked very red against the green Formica tabletop. So that meant he had spoken to one of them. Who was the most likely to have picked up the book? My money was on Serena.

“That was stupid of me,” I said. “I would have hated to have lost it. Did Serena find it?”

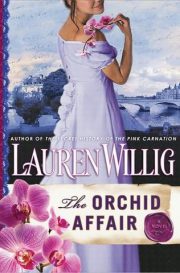

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.