“Even so, retain your friendship with him, as I will,” I write cautiously to Henry in reply. “Cecil plays a long game and the queen loves those who protected her as princess.”

My whole household is to move to my husband’s great palace at Wingfield with the Scots queen, and she is radiant at the chance of getting away from Tutbury. Nothing is too much trouble for her: she arranges her own household’s packing into wagons; her own goods, clothes, and jewels are ready to go at dawn. Her pet birds are in their boxes; she swears her dog will sit on anyone’s saddlebow. She will ride ahead with my husband, the earl; as usual, I am to follow with the household goods. I shall trail behind them like their servant. I shall ride in the mud churned up by the hooves of their horses.

It is a beautiful morning when they set off, and the spring birds are singing, larks rising into the warm air as they go over the moor. It starts to rain by the time I have the baggage train packed and ready to go and I pull my hood up over my head, mount my horse, and lead the way out of the yard and down the muddy hill.

We go painfully slow. My husband the earl and the queen can canter on the grassy verges, and he knows the bridleways and shortcuts through woods and leads her splashing through streams. They will have a pleasant journey through the country with half a dozen companions. They will gallop on the high moors and then drop down to the shaded paths beside the rivers where the trees make an avenue of green. But I, fretting about the wagons and the household goods, have to go as slowly as the heaviest cart can lumber along the muddy lanes. When we lose a wheel, we all halt for several hours in the rain to make repairs; when a horse goes lame, we have to stop and take it from the shafts, and hire another at the next village. It is hard labor and I might begrudge it if I had been born and raised as a lady. But I was not born a lady; I was born and raised as a working woman and I still take great joy in doing hard work, and doing it well. I don’t pretend to be a lady of leisure. I have worked for my fortune and I take a pride in it. I am the first woman in my family to rise from poverty by my own efforts; actually I am the first woman in Derbyshire to own great property in my own right. I am the first woman that I know to use my own judgment to make and keep a fortune. This is why I love the England of Elizabeth: because a woman like me, born as low as me, can make and keep my own fortune.

The last few miles of the journey to Wingfield follow the course of the river. It is evening by the time we get there and at least the rain has lifted. I am wet through, but at any rate I can put back my hood and look around me at the most beautiful approach to my lord’s favorite house. We ride along the floor of the valley, with moorhen scuttering away into the water of the river and lapwing calling in the evening sky, then we round the corner and see, across the water meadows, the beautiful palace of Wingfield, rising above the trees, like a heavenly kingdom. The marshes lie beneath it with mist coiling off the waters; I can hear the croaking of frogs and the booming of the bittern. Above the water is a thick belt of trees, the ash coming green at last, the willows whispering in thick clumps. A throstle thrush sings, its warble sharp against the dusk, and there is a whisper of white like a ghost as a barn owl sweeps past us.

This is a Talbot property, belonging to my husband, inherited from his family, and I never see it without thinking how well I have married: that this palace should be one of the great houses that I may count as my home. It is a cathedral, it is an etching of stone against sky. The high arched windows are traceries of white stone, the turrets ethereal against the evening sky, the woods like billowing clouds of fresh green below it, and the rooks are cawing and settling for the night as we ride up the muddy track towards the house and they throw open the great gates.

I had sent half my household ahead of us to prepare, so that when the queen and my husband the earl rode in together, hours earlier, they arrived in afternoon sunshine and to a band of musicians. When they entered the great hall there were two huge fires either end of the room to warm them, and the servants and the tenantry lined up, bowing. By the time I arrive, at dusk, with the rest of the household furniture, the valuables, and the portraits, gold vessels, and other treasures, they are already at dinner. I go in to find them seated in the great hall, just the two of them at the high table, she in my husband’s place, her cloth of estate over her throne, thirty-two dishes before her, my husband seated on an inferior chair just below her, serving her from a great silver tureen, collected from an abbey, with the abbot’s own golden ladle.

They do not even see me when I enter at the back of the hall, and I am about to join them, when something makes me hesitate. The dirt from the road is in my hair and on my face, my clothes are damp, I am muddy from my boots to my knees, and I smell of horse sweat. I hesitate, and when my husband the earl looks up from his dinner I wave and point towards the great stairs to our bedchamber, as if I am not hungry.

She looks so fresh and so young, so pampered in her black velvet and white linen, that I cannot bring myself to join them at the dining table. She has had time to wash and change her clothes; her dark hair is like a swallow’s wing, sleek and tucked up under her white hood. Her face, pale and smooth, is as beautiful as a portrait as she looks down the hall and raises her white hand to me and smiles her seductive smile. For the first time in my life, for the first time ever, I feel untidy; worse, I feel…old. I have never felt this before. All through my life, through the courtships of four husbands, I have always been a young bride, younger than most of their household. I have always been the pretty young woman, skilled in household arts, clever at managing the people who work for me, neat in my dress, smart in my clothes, remarkable for wisdom beyond my years, a young woman with all her life before her.

But tonight, for the first time ever, I realize that I am not a young woman anymore. Here, in my own house, in my own great hall, where I should be most at ease in my comfort and my pride, I see that I have become an older woman. No, actually not even that. I am not an older woman: I am an old woman, an old woman of forty-one years. I am past childbearing; I have risen as high as I am likely to go; my fortunes are at their peak; my looks can now only decline. I am without a future, a woman whose days are mostly done. And Mary Queen of Scots, one of the most beautiful women in the world, young enough to be my daughter, a princess by birth, a queen ordained, is sitting at dinner, dining alone with my husband, at my own table, and he is leaning towards her, close, closer, and his eyes are on her mouth and she is smiling at him.

1569, MAY,

WINGFIELD MANOR:

GEORGE

Iam waiting with the horses in the great courtyard of the manor when the doors of the hall open, and she comes out, dressed for riding in a gown of golden velvet. I am not a man who notices such things, but I suppose she has a new gown, or a new bonnet, or something of that nature. What I do see is that in the pale sunshine of a beautiful morning she is somehow gilded. The beautiful courtyard is like a jewel box around something rare and precious, and I find myself smiling at her, grinning, I fear, like a fool.

She steps lightly down the stone stairs in her little red leather riding boots and comes to me confidently, holding out her hand in greeting. Always before, I have kissed her hand and lifted her into the saddle without thinking about it, as any courtier would do for his queen. But today I feel suddenly clumsy, my feet seem too big, I am afraid the horse will move away as I lift her, I even think I may hold her too tightly or awkwardly. She has such a tiny waist, she is no weight at all, but she is tall, the top of her head comes to my face. I can smell the light perfume of her hair under her golden velvet bonnet. For no reason I feel I am growing hot, blushing like a boy.

She looks at me attentively. “Shrewsbury?” she asks. She says it “Chowsbewwy?” and I hear myself laugh from sheer delight at the fact that still she cannot pronounce my name.

At once her face lights up with reflected laughter. “I still cannot say it?” she asks. “This is still not right?”

“Shrewsbury,” I say. “Shrewsbury.”

Her lips shape to make the name as if she were offering me a kiss. “Showsbewy,” she says and then she laughs. “I cannot say it. Shall I call you something else?”

“Call me Chowsbewwy,” I say. “You are the only person ever to call me that.”

She stands before me and I cup my hands for her booted foot. She takes a grip of the horse’s mane, and I lift her, easily, into the saddle. She rides unlike any woman I have ever known before: French-style, astride. When my Bess first saw it, and the manilla pantaloons she wears under her riding habit, my wife swore that there would be a riot if she went out like that. It is so indecent.

“The Queen of France herself, Catherine de Medici, rides like this, and every princess of France. Are you telling me that she and all of us are wrong?” Queen Mary demanded, and Bess blushed scarlet to her ears and begged pardon and said that she was sorry but it was odd to English eyes, and would the queen not ride pillion, behind a groom, if she did not want to go sidesaddle?

“This way, I can ride as fast as a man,” Queen Mary said, and that was the end to it, despite Bess’s murmur that it was no advantage to us if she could outride every one of her guards.

From that day she has been riding on her own saddle, astride like a boy, with her gown sweeping down on either side of the horse. She rides, as she warned Bess, as fast as a man, and some days it is all I can do to keep up with her.

I make sure that her little heeled leather boot is safe in the stirrup, and for a second I hold her foot in my hand. She has such a small, high-arched foot, when I hold it I can feel an odd tenderness towards her. “Safe?” I ask. She rides a powerful horse; I am always afraid it will be too much for her.

“Safe,” she replies. “Come, my lord.”

I swing into the saddle myself and I nod to the guards. Even now, even with the plans for her return to Scotland in the making, her wedding planned to Norfolk, her triumph coming at any day now, I am ordered to surround her with guards. It is ridiculous that a queen of her importance, a guest in her cousin’s country, should be so insulted by twenty men around her whenever she wants to ride out. She is a queen, for heaven’s sake; she has given her word. Not to trust her is to insult her. I am ashamed to do it. Cecil’s orders, of course. He does not understand what it means when a queen gives her word of honor. The man is a fool and he makes me a fool with him.

We clatter down the hill, under the swooping boughs of trees, and then we turn away to ride alongside the river through the woods. The ground rises up before us and we come out of the trees when I see a party of horsemen coming towards us. There are about twenty of them, all men, and I pull up my horse and look back at the way we have come and wonder if we can outride them back to home, or if they would dare to fire on us.

“Close up,” I call sharply to the guards. I feel for my sword but of course I am not wearing one, and I curse myself for being overconfident in these dangerous times.

She glances up at me, the color in her cheeks, her smile steady. She has no fear, this woman. “Who are these?” she asks, as if it is a matter of interest and not hazard. “We can’t win a fight, I don’t think, but we could outride them.”

I squint to see the fluttering standards and then I laugh with relief. “Oh, it is Percy, my lord Northumberland, my dearest friend, and his kin, my lord Westmorland, and their men. For a moment I thought that we were in trouble!”

“Oh, well met!” Percy bellows as he rides towards us. “A lucky chance. We were coming to visit you at Wingfield.” He sweeps his hat from his head. “Your Grace,” he says bowing to her. “An honor. A great honor, an unexpected honor.”

I have been told nothing of this visit, and Cecil has not told me what to do if I have noble visitors. I hesitate, but these have been my friends and my kin for all my life; I can hardly make them strangers at my very door. The habit of hospitality is too strong in me to do anything but greet them with pleasure. My family have been Northern lords for generations; all of us always keep open house and a good table for strangers as well as friends. To do anything else would be to behave like a penny-pinching merchant, like a man too mean to have a great house and a great entourage. Besides, I like Percy, I am delighted to see him.

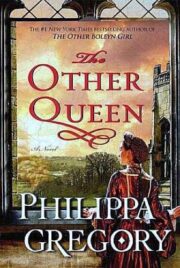

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.