“No,” she says. “It is yours. It is all yours.”

1570, AUGUST,

WINGFIELD MANOR:

MARY

My darling Norfolk, for we are still betrothed to marry, copies to me the playscript of the charade he must act. He has to make a complete submission to his cousin the queen, beg her pardon, assure her that he was entrapped into a betrothal with me under duress and as a fault of his own vanity. The copy that he sends me of his submission, for my approval, is so weepingly guilty, such a bathetic confession of a man unmanned, that I write in the margin that I cannot believe even Elizabeth will swallow it. But, as so often, I misjudge her vanity. She so longs to hear that he never loved me, that he is hers, all hers, that they are all of them, all her men, all of them in love with her, all of them besotted with her poor old painted face, her bewigged head, her wrinkled body, she will believe almost anything—even this mummery.

His groveling makes its own magic. She releases him, not to return to his great house in Norfolk, where they tell me that his tenants would rise up for him in a moment, but to his London palace. He writes to me that he loves this house, that he will improve and embellish it. He will build a new terrace and a tennis court, and I shall walk with him in the gardens when we pay our state visits as King Consort and Queen of Scotland. I know he thinks also of when we will inherit England. He will improve this great house so that it will be our London palace; we will rule England from it.

He writes to me that Roberto Ridolfi is thankfully spared and is to be found in the best houses in London again, knowing everyone, arranging loans, speaking in whispers of my cause. Ridolfi must have nine lives, like a cat. He crosses borders and carries gold and services plots and always escapes scot-free. He is a lucky man, and I like to have a lucky man in my service. He seems to have strolled through the recent troubles, though everyone else ended up in the Tower or exile. He went into hiding during the arrests of the Northern lords, and now, protected by his importance as a banker and his friendship with half the nobles of England, he is at liberty once more. Norfolk writes to me that he cannot like the man, however clever and eager. He fears Ridolfi is boastful and promises more than he can achieve, and that he is the very last visitor my betrothed wants at Howard House, which is almost certainly watched day and night by Cecil’s men.

I reply that we have to use the instruments that come to hand. John Lesley is faithful but not a man of action, and Ridolfi is the one who will travel the courts of Europe seeking allies and drawing the plots together. He may not be likable—personally, I have never even laid eyes on him—but he writes a persuasive letter and he has been tireless in my cause. He meets with all the greatest men of Christendom and goes from one to another and brings them into play.

Now he brings a new plan from Philip of Spain. If these present negotiations to return me to my throne break down again, then there is to be an uprising by all the English lords—not just those of the North. Ridolfi calculates that more than thirty peers are secret Papists—and who should know better than he who has the ear of the Pope? The Pope must have told him how many of Elizabeth’s court are secretly loyal to the old faith. Her situation is worse than I realized if more than thirty of her lords have secret priests hiding in their houses and take Mass! Ridolfi says they only need the word to rise, and King Philip has promised to provide an army and the money to pay them. We could take England within days. This is “the Great Enterprise of England” remade afresh, and though my betrothed does not like the man, he cannot help but be tempted by the plan.

“The Great Enterprise of England,” it makes me want to dance, just to hear it. What could be greater as an enterprise? What could be a more likely target than England? With the Pope and Philip of Spain, with the lords already on my side, we cannot fail. “The Great Enterprise,” “the Great Enterprise,” it has a ring to it which will peal down the centuries. In years to come men will know that it was this that set them free from the heresy of Lutheranism and the rule of a bastard usurper.

But we must move quickly. The same letter from Norfolk tells me the mortifying news that my family, my own family in France, have offered Elizabeth an alliance and a new suitor for her hand. They do not even insist on my release before her wedding. This is to betray me; I am betrayed by my own kin who should protect me. They have offered her Henri d’Anjou, which should be a joke, given that he is a malformed schoolboy and she an old lady, but for some reason, nobody is laughing and everyone is taking it seriously.

Her advisors are all so afraid of Elizabeth dying, and me inheriting, that they would rather marry her to a child and have her die in childbirth, old as she is, old enough to be a grandmother—as long as she leaves them with a Protestant son and heir.

I have to think that this is a cruel joke from my family on Elizabeth’s vanity and lust, but if they are sincere, and if she will go through with it, then they will have a French king on the throne of England, and I will be disinherited by their child. They will have left me in prison to rot and put a rival to me and mine on the English throne.

I am outraged, of course, but I recognize at once the thinking behind this strategy. This stinks of William Cecil. This will be Cecil’s plan: to split my family’s interests from mine, and to make Philip of Spain an enemy of England forever. It is a wicked way to carve up Christendom. Only a heretic like Cecil could have devised it, but only faithless kin like my own husband’s family are so wicked that they should fall in with him.

All this makes me determined that I must be freed before Elizabeth’s misbegotten marriage goes ahead, or if she does not free me, then Philip of Spain’s armada must sail before the betrothal and put me in my rightful place. Also, my own promised husband, Norfolk, must marry me and be crowned King of Scotland before his cousin Elizabeth, eager to clear the way for the French courtiers, throws him back in the Tower. Suddenly, we are all endangered by this new start of Elizabeth, by this new conspiracy of that archplotter Cecil. Altogether, this summer, which seemed so languid and easy, is suddenly filled with threat and urgency.

1570, SEPTEMBER,

CHATSWORTH:

BESS

Abrief visit for the two of them to Wingfield—the cost of the carters alone would be more than her allowance if they ever paid it—and then they are ordered back to Chatsworth for a meeting which will seal her freedom. I let them go to Wingfield without me; perhaps I should attend on her, perhaps I should follow him about like a nervous dog frightened of being left behind, but I am sick to my soul at having to watch my husband with another woman and worrying over what should be mine by right.

At Chatsworth at least I can be myself, with my sister and two of my daughters who are home for a visit. With them I am among people who love me, who laugh at silly familiar jokes, who like my pictures in the gallery, who admire my abbey silver. My daughters love me and hope to become women like me; they don’t despise me for not holding my fork in the French style. At Chatsworth I can walk around my garden and know that I own the land beneath my boots and no one can take it from me. I can look out my bedroom window at my green horizon and feel myself rooted in the country like a common daisy in a meadow.

Our peace is short-lived. The queen is to return and my family will have to move out to accommodate her court and the guests from London. As always, her comfort and convenience must come first, and I have to send my own daughters away. William Cecil himself is coming on a visit with Sir Walter Mildmay and the Queen of Scots’ ambassador, the Bishop of Ross.

If I had any credit with the merchants or any money in the treasure room I would be bursting with pride at the chance to entertain the greatest men of the court, and especially to show Cecil the work I have done on the house. But I have neither, and in order to provide the food for the banquets, the fine wines, the musicians, and the entertainment, I have to mortgage two hundred acres of land and sell some woodland. My steward comes to my business room and we look at each parcel of land, consider its value and if we can spare it. I feel as if I am robbing myself. I have never parted with land before but to make a profit. I feel as if every day the fortune that my dear husband Cavendish and I built up so carefully, with such determination, is squandered on the vanity of one queen who will not stop spending and will repay nothing, and the cruelty of another who now delights in punishing my husband for his disloyalty by letting his debts rise up like a mountain.

When William Cecil arrives with a great entourage, riding a fine horse, I am dressed in my best and at the front of the house to greet him, no shadow of anxiety on my face or in my bearing. But as I show him around and he compliments me on everything I have done to the house, I tell him frankly that I have had to cease all the work, lay off the tradesmen, dismiss the artists, and indeed I have been forced to sell and mortgage land, to pay for the cost of the queen.

“I know it,” he says. “Bess, I promise you, I have been your honest advocate at court. I have spoken to Her Grace as often and as boldly as I dare for you. But she will not pay. All of us, all her servants, are impoverished in her service. Walsingham has to pay his spies with his own coin and she never repays him.”

“But this is a fortune,” I say. “It is not a matter of some bribes for traitors and wages for spies. This is the full cost of running a royal court. Only a country paying taxes and tithes could afford her. If my lord were a lesser man she would have ruined him already. As it is he cannot meet his other debts. He does not even realize how grave is his situation. I have had to mortgage farms to cover his debts; I have had to sell land and enclose common fields; soon he will have to sell his own land, perhaps even one of his family houses. We will lose his family home for this.”

Cecil nods. “Her Grace resents the cost of housing the Scots queen,” he says. “Especially when we decode a letter and find that she has received a huge purse of Spanish gold, or that her family have paid her widow’s allowance and she has paid it out to her own secret people. It is Queen Mary who should be paying you for her keep. She is living scot-free on us while our enemies send her money.”

“You know she never will pay me,” I protest bitterly. “She pleads poverty to my lord, and to me she swears she will never pay for her own prison.”

“I will speak to the queen again.”

“Would it help if I sent her a monthly bill? I can prepare the costs for every month.”

“No, she would hate that even worse than one bigger demand. Bess, there is no possibility that she will fully repay you. We have to face it. She is your debtor and you cannot force her to pay.”

“We will have to sell yet more land then,” I say gloomily. “Pray God you can take the Scots queen off our hands before we are forced to sell Chatsworth.”

“Good God, Bess, is it that bad?”

“I swear to you: we will have to sell one of our great houses,” I say. I feel as if I am telling him that a child will die. “I will lose one of my properties. She will leave us with no choice. Gold drains away in the train of the Scots queen and nothing comes in. I have to raise money from somewhere, and soon all we will have left to sell is my house. Think of me, Master Cecil, think of where I have come from. Think of me as a girl who was born to nothing but debt and has risen as high as the position I now enjoy, and now think of me having to sell the house that I bought and rebuilt and made my own.”

1570, SEPTEMBER,

CHATSWORTH:

MARY

B—

I will not fail now. This is my chance. I will not fail you. You will see me on my throne again and I shall see you at the head of my armies.

M

This is my great chance to seduce Cecil and I prepare as carefully as a general on campaign. I do not greet him as he arrives; I let Bess supervise the dinner and so wait until he has rested from his journey, dined well, drunk a little, and then I plan my entrance to the Chatsworth dining hall.

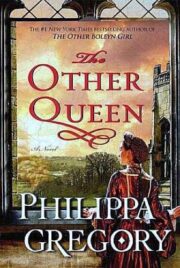

"The other queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The other queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The other queen" друзьям в соцсетях.