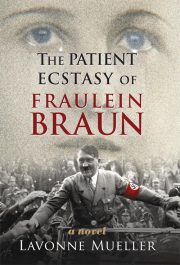

Lavonne Mueller

THE PATIENT ECSTASY OF FRÄULEIN BRAUN

A NOVEL

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.”

“The world that comes after the Führer and national socialism is not any longer worth living… therefore I took the children with me.”

“The more we do to you, the less you seem to believe we are doing it.”

1

THE BUNKER IS PART OF MY BEING. Out of love for him, I greedily seize this underground as mine. Through all its systems of vitality and power, the Bunker is a pulse, a throbbing that I know is His heart.

When I saw my first rat, I didn’t scream. Adi warned me there would be rats. It’s normal for them to hunker in with us. But I thought I’d only see one at night. This was early morning and it was brown, though I expected black. Chewing through the concrete with tiny hard incisors, its skeleton conveniently collapsed so it could worm inside a two-inch hole. I was fascinated and determined not to be afraid like Magda and the children who yell and have Papa Josef and his orderly run all over shooting at the beasts. No, I don’t scream for help. I observe them. That first time, I waited. The rat stood in front of its hole, his head angled to one side as if casually looking at me. He was after food, and I made certain from the very beginning that I would never have a crumb in my room. Eliminating food is the only way to control them. Because of the Goebbels’ children, we’re reluctant to put down poison traps. So this brown demon went back and forth in front of his hole, pacing. Another one came out and paced with him. Then a third. Goebbels’ war films have rats running across the screen for several minutes, then the rats gradually turn into Jews. But looking closely at these creatures, I could only find the sinister eyes of Bormann as he goes topside to find abandoned furniture and jewelry for his wife, Gerda.

Goebbels tried to lessen his children’s fear of rats by taping a dead one stained with its own blood in a picture book. But that didn’t stop their screaming, and the “rat book” was thrown away.

Rommel told Adi about desert rats, huge creatures that banged their tails on the sand to attract the female.

Often the bomb shuddering walls keep the vermin in their hole though Adi tells me rats can mate up to 20 times a day. I try not to think of rodents enjoying themselves and making thousands of awful babies.

I have learned to live with secretive rats. Most of the time, they’re no bother. Their chewing at night is not as bad as the screech-bombs above with their high piercing scream. My concern now is to make my home as pretty as possible.

I must set down every moment I’ve been with him. I once read that to destroy a man you have to destroy his past. I won’t let that happen to Adi. I will record everything, writing without vanity… only the truth and from my own experience. Because I can’t keep it in. I’ll mark him with sentences that are without prejudice and guile. Here in this memoir, my Adi will always be loved and never forgotten.

April 1945—The Führerbunker. The first time we were intimate, I knew it would be different. You have to expect that with a genius. But my sister, Gretl, says there’s just so many ways the “manhood” can be used—even with a genius. My sister is wrong.

Dr. Morell, blond and wearing a long white coat reaching down to his highly polished boots, positioned me in great modesty with sheets draped around my thighs and stomach so that only my pubes were visible. Pursing his very thin lips and clicking his iron-studded heels together, he inserted the exercise-bar in my womb without even removing the silver Goethe ring on his right hand. I didn’t startle as the thoughtful doctor had heated the bar beforehand in hot towels. I was told to clench… release. Clench… release. Already I was longing, with the flexible metal inside me, longing for the man who is the steel and chrome of Germany itself.

Dr. Morell calls the device he invented V-Volk. Vaginal Volk. It’s a yielding little rod for developing muscles to make me a superior German woman internally. There’s no question, the doctor tells me, that I’m superior on the outside. “You’re the daughter I never had,” he says as he pats my thigh. (It was nearly a year before I knew he already had a daughter.)

My loving Führer is masterful. I lie flat on the bed, knees bent, my lower body tilting upwards. Lubricating the 7-inch Krupp steel V-V with warm butter, he inserts it slowly and gently. I clench my pelvis muscles around it as Dr. Morell taught me to do. My sweet Führer chants: “Pull. It creates resistance. Pull. Work your muscles. Work.” He places an egg timer on top of the headboard. The V-Volk slips… slides ever so slightly. I’m in training. He breathes heavily. Not like a common man. No. His heavy breathing is lyrical for my beloved’s body is so finely tuned that his enormous capillaries must gather around his blood cells one at a time—careful to be unique even there.

Lying stiffly next to me, he talks about the perfect copulation he saw on the battlefield. Two seriously wounded men lay one on top of the other (he pulls me over him). The bottom man was a German soldier, the top one a French soldier. Both men were in great pain, their blood dripping to the ground. There were cries of agony, the German calling to the Frenchman on top, the Frenchman to the German on the bottom. Back and forth, (we rock), death rattling calls of utmost tenderness—enemy to enemy. Pain gripped each soldier with equal force. They were embraced in misery. (Suddenly, my lover’s voice now becomes high pitched and excited, his glorious part swelling). The German on the bottom began to slowly shift his arm toward something. His sleeve was drenched in sparkling red blood as he moved his arm inch by inch. The German finally stretched his fingers to reach a hand grenade to pull the pin—to end the pain for himself and his suffering enemy on top. Both exploded in shiny dark plugs of dust, varnishing in the air (as my love snakes his hand inside me and is soon released).

“My precious little grenade,” he moans.

For nearly an hour, we lie still, silent, thinking only of this love story, letting the memory of those two soldiers rub against our senses until I caress the frill of skin around his manhood and he shoves against the metal of the V-Volk, the tip of his hot full member ramming the Volk inside me. The phonograph plays and he adjusts his peak to Wagner’s climax. Even though his gift doesn’t touch me, I still feel a glorious blend of man, steel and music—a triumphant ménage a trois—as he explodes, dripping down my thighs like goat cheese brie, ripe and silty. Then he wipes his “genius” with a clean handkerchief he keeps by his bedside and later burns in a metal tray as there is the danger someone will use his specimen to create another Führer.

“You always make my badge live again,” he rumbles sweetly.

“No badge is less dead than yours. I love you,” I say softly.

“What would you like me to give you?”

“Three words: I… love… you.”

“Evchen, I’m wedded to Germany. You know that.”

“Is there no love left for me?”

“My little grenade, you are very special. Now, what can I give you?”

“A pink flamingo.”

“I’ll have one sent to the Berlin Zoo.”

“I want one on a scarf.”

“Done!” Instead of an SS salute with outstretched hand, he gives me a tender military salute from his forehead to mine that’s as soft and caressing as a love pat.

I’m not physically satisfied after these love sessions. It’s enough to see his neck relax and his shoulders go limp. Afterward, he slowly puts on his Schnurrbartbinde—the little bandage he wears at night to keep his mustache flat and straight. I can’t sleep because of passion cramps, but I’d never let him know he’s caused me pain.

After all these years we’ve been together, there are still only V-Volk nights. Even here in the Bunker. Though he doesn’t permit himself the full measure, the desire to do so is a great comfort to me. But I’m waiting patiently for that time soon when I’ll finally have all of Him.

When we first met, I was young and naïve and had no idea how important he was. He was introduced to me as Herr Wolf, an alias used during his early years. I knew he was considered up and coming in the government, but so were a lot of men who asked me out when I was working at Herr Hoffmann’s photo shop at 42 Wiedenmeyerstrasse in Munich. Herr Wolf would stop by now and then to buy film and look at the new cameras. Many books were behind glass along the store’s back wall and that’s where he told me most books belong—behind glass. I said that when I was bored and there were no customers, I would read the titles of the many volumes out loud to pass the time. I couldn’t know then that he was an author himself as he didn’t look like a man who ever hunched over stacks of papers but was someone with a certain upright vitality.

He would often talk to Albrecht, the parakeet in a cage by the door. When I asked him why he didn’t take a picture of Albrecht, he said: “Why photograph what is already alive.”

“Does that mean you would never photograph a woman… such as me, Herr Wolf?”

He smiled and said cryptically: “Perhaps if you were a building.”

“That sounds very Art deco,” I offered, proud to be able to spar with him. I took one of the empty boxes from behind the counter. One slat was gone from the side giving the appearance—if one had an imagination—of an open window. I pushed my head against the opening like a human frame and waved at him. “Now will you photograph me?”

He answered with a quizzing stare, his mustache slightly twitching upward, a mustache so perfectly even that one side was exactly the same thickness as the other side. But I could tell he was amused.

Just then Hoffmann arrived and quickly grabbed a camera to take a delightful picture. But Herr Wolf roughly snatched the camera from Hoffmann, yanked away the box that still covered my head and shouted: “I don’t allow impromptu shots.” Later, as the Führer, when he was continually photographed, he would carefully stage each and every pose and forbid any picture when he wore his reading glasses. “A photograph is a reflection with a past,” he announced preferring the colored postcards of himself painted by the famous W. Willrich.

Though his pale blue eyes were fetching, I didn’t find Herr Wolf particularly mysterious or superhuman. He seemed very ordinary except for an Austrian charm in regards to our parakeet bringing his rain cape to hang around the sides of the cage so that Albrecht wouldn’t get chilled. Telling Herr Hoffmann never to buy Albrecht a wife, he explained that a parakeet would ignore people and concentrate on his mate.

We had a fish bowl on the counter and when one of them gave birth, I delivered the baby to Hoffmann’s eight-year-old niece, Hertha, for her birthday. When Herr Wolf found out, he was angry saying it was wrong to separate a mother from her child. I had to put the baby fish back in the bowl, and poor Hertha went without a gift.

Herr Wolf would often talk to Hoffmann about Arnold Fanck who experimented with lenses, camera speeds, and film stocks. They considered him a great artist who used high-contrast images and backlighting and even went so far as to put cameras to his skis for daring downhill-racer shots. But I thought Fanck was rather silly as his pictures didn’t look normal.

For many days Herr Wolf deliberated over buying either a Minox or the new Leica II. Hoffmann talked endlessly about the importance of the Leica’s trigger operated shutter, flat range finder top, and lens with click locking apertures. One Saturday, Herr Wolf finally bought the Leica II realizing, he said, that a superior camera would free him from any prison-hours of idleness. Afterward he walked directly over to me as I was changing Albrecht’s water and said earnestly in his soft Austrian accent: “Do you enjoy watching elegant and important people?” At first I was a little annoyed because I did get to see certain famous persons who came by the shop to talk with Herr Hoffmann who himself is prominent and happens to be an outstanding photographer. And I had often attended quaint parties in Schwabing, Munich’s Latin Quarter. I like to be where the songs are sung. I didn’t consider myself a stupid country girl, even back then. But my mother always told me: “One can eat with a knife and fork and still lack gentlemanly common sense.”

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.