They had reached the walled city of Vitry.

There was little defence offered and in a short time the King’s men were in the streets killing, pillaging, shedding the blood of its inhabitants. The old and the maimed and the women and the children ran screaming before the soldiers and barricaded themselves into the wooden church.

‘Enough, enough,’ cried Louis. But his command was not heeded.

His followers had come to pillage and murder and they could not be restrained. There then occurred a terrible incident which was to haunt the King for the rest of his days.

Inside the church the children clung to their mothers, and mothers begged for the safety of their little ones. The King’s men knew no pity. They did not attempt to break into the church. They merely set it on fire.

As the flames enveloped it and the thick black smoke filled the air the cries of the innocent could be heard calling curses on their murderers and screaming for mercy.

‘Have done. Have done,’ pleaded Louis but they would not listen to him. In any case it was too late. In that burning church were thirteen hundred innocent people and they were all burned to death.

In his tent Louis lay staring blankly before him. Eleonore lay beside him.

‘I can hear their screaming,’ he said.

She answered: ‘There is no sound now. They are all dead.’

‘All dead!’ he cried. ‘Those innocent people. Holy Mother of God help me! I shall never be able to escape from the sound of their cries.’

‘They should have denounced their lord. They should have sworn allegiance to you.’

‘They were innocent people. What did they know of our quarrel?’

‘You must try to sleep.’

‘To sleep. If I do, I dream. I can smell the smoke. I shall never be free of it. How the wood crackled!’

‘It was old and dry,’ she said.

‘And little children … They called curses on us. Imagine a mother … with her little ones.’

‘It is war,’ said Eleonore. ‘It is not wise to brood on these things.’

But Louis could not stop brooding.

He could not go on, he declared.

‘To give in now would be victory for Theobald,’ Eleonore reminded him.

‘I can’t help it,’ cried Louis. ‘I am sick of war and killing.’

‘You should never have been a king.’

‘You speak truth. My heart is in the Church.’

‘Which is no place for a king’s heart to be.’

‘Sometimes I think I should have refused to take the crown.’

‘How could you, the King’s son, have done that?’

‘Sometimes I think God is not pleased with me. We have been six years married and have no child.’

‘It is a long time to wait,’ agreed Eleonore.

‘Is there something we have done … or not done? Have I displeased God in some way?’ The King shivered. ‘I feel in my heart that whatever we did before the burning of Vitry was nothing compared with that great sin.’

‘Stop thinking of it.’

‘I can’t, I can’t,’ moaned the King.

She knew that he would be useless to command an army in his present state.

‘We should return to Paris,’ she said.

He was eager to agree. ‘Yes,’ he answered. ‘Disband the army. Go back. Call off the war.’

‘That would be folly. The army will stay here. We shall return. State duties call you to Paris. There you will rest and forget Vitry. You will learn that it is what must be expected in war.’

The war continued. Louis was heartily sick of it but Eleonore would not allow Theobald to have the chance to say the King had been forced to retire from the field.

The King’s ministers begged him to consider what good there was in continuing. Louis would have agreed but he dared not face Eleonore’s wrath.

He could not understand his feeling for her. It was as though he were under a spell. Whatever he might promise to do, when she showed her contempt for his weakness he always gave way to her.

The Abbot of Clairvaux, who had prophesied the death of Louis’s brother Philippe, had become known as a worker of miracles. He had ranged himself against Louis and Eleonore, and came to the court to ask the King to agree to a peace.

Eleonore would not hear of this.

She faced the Abbot and explained to him that to agree to a peace would be to dishonour her own sister, and although this was but one of the causes which had made it necessary for Louis to make war, it was a very important one.

‘Such a war,’ the Abbot told her, ‘is displeasing to God. Has that not been made clear? God has turned his face from your endeavours. The King suffers deep remorse. He has done so since the burning of Vitry.’

‘And before that,’ said Eleonore bitterly. ‘He has rendered me childless. You, who are said to have the power to make miracles, could perhaps work this one for me if you would.’

The Abbot was thoughtful.

‘Whether you should have the blessing of a child is in the hands of God.’

‘So is all that happens. Yet you have worked miracles, they say. Why do you not work one now?’

‘I could do nothing in this matter.’

‘You mean you will not help me?’

‘If you had a child you would doubtless change your life. Perhaps you need a child.’

‘I need a child,’ said Eleonore. ‘Not only because my son will be the heir to France, but because I long for a child of my own.’

The Abbot nodded.

She caught his arm. ‘You will do this for me?’

‘My lady, I cannot. It is in the hands of God.’

‘If I persuaded the King to stop the war, to call a truce …’

‘If you did that it might be that God would be more ready to listen to your prayers.’

‘I would do anything to get a child.’

‘Then pray with me, but first humble yourself before God. You cannot do that with the sin of war upon you.’

‘If there was peace you would work the miracle?’

‘If there were peace I should be able to ask God to grant your request.’

‘I will speak to the King,’ she said.

She did and the result was that there was peace between Theobald and Louis.

To Eleonore’s great joy she was pregnant. She was sure that Bernard had worked the miracle. All these years and no sign of a child, and now the union would be fruitful.

She had softened a little. She was planning for the child as a humble mother might have done. The songs she sang were of a different nature.

The members of the court marvelled.

In due course the child was born. A girl.

She was not disappointed. Like all rulers Louis had hoped for a son; yet, she demanded of her ladies, why should there be this overwhelming adoration of the male? ‘I was my father’s heiress although I was a woman,’ she reminded them. ‘Why should the King and I be sad because we have a daughter?’

The Salic law prevailed in France. This meant that no woman could rule. The crown would go to the next male heir. This law was all against Eleonore’s principles and she promised herself that she would not allow it to persist. Her daughter was but a baby yet and there was time enough to think of her future.

She was christened Marie and for more than a year after her birth Eleonore was content to play the devoted mother.

Life had become monotonous. Little Marie was past two years old. Eleonore was devoted to her but naturally the child was often in the company of her nurses. Eleonore continued to hold court. The songs had become more voluptuous again; they stressed the sorrows of unrequited passion and the joys of shared love.

Petronelle was her constant companion; Eleonore watched with smouldering eyes her sister and her husband together. What a passionate affair that had been! Something, sighed Eleonore, which was denied me.

She had at first been fond of Louis. He had been so overcome at the sight of her and was so devoted to her that she had developed quite an affection for him. It was not in her passionate nature to be contented with that. Louis might be her slave and it pleased her that he should be, but his piety bored her, and what was hardest of all to endure was his remorse.

He took a great interest in the Church and was constantly taking part in some ritual. He would return from such occasions glowing with satisfaction but it would not be long before he was sunk in melancholy.

He could not forget the sound of crackling flames and the screams of the aged and innocent as they had burned to death. The town itself had now become known as Vitry-the-Burned.

He would pace up and down their bedchamber while Eleonore watched him from their bed.

She knew that he would not be seeing her, seductively inviting with her long hair loose about her naked shoulders as she might be. He would be seeing the pitiless faces of men intent on murder; and when she spoke to him he would hear instead those cries for mercy.

How many times had she told him: ‘It was an act of war and best forgotten.’

And he declared: ‘To my dying day I shall never forget. Remember, Eleonore, all that was done was done in my name.’

‘You did your best to stop it. They heeded you not.’ Her lips curled. What a weakling he was! His men intent on murder did not obey him! And he permitted this.

He should have been a monk.

She was weary of him. She wished they had married her to a man.

Yet he was the King of France and marriage to him made her a queen. But she was also Eleonore of Aquitaine. She was never going to forget that.

So she listened to him wandering on in his maudlin way and she knew that she would not go on for ever living as she was at this time. Her adventurous spirits were in revolt.

She had made a brilliant marriage; she was a mother. But for her that was not enough. She was reaching for adventure.

The opportunity came from an unexpected quarter.

For many years men had sought to expiate their sins by making pilgrimages to Jerusalem. They had believed that by undertaking an arduous journey, which often resulted in death, they showed their complete acceptance of the Christian faith and their desire for repentance. They believed that in this way they could be forgiven a life of wickedness. There had been many examples of men who had undertaken this pilgrimage. Robert the Magnificent, father of William the Conqueror, had been one. He had died during the journey leaving his son but a child, unprotected from his enemies, but it was believed that he had expiated a lifetime’s sins by this gesture.

But while it was considered a Christian act to make a pilgrimage, how much greater grace could be won by taking part in a Holy War to drive the infidel from Jerusalem.

Ever since the seventh century Jerusalem had been in the possession of the Mussulmans, khalifs of Egypt or Persia. There was conflict between Christianity and Islamism, and at the beginning of the eleventh century the persecution of Christians in the Holy Land was at its most intense. All Christians living in Jerusalem were commanded to wear a wooden cross about their necks. As these weighed five pounds they were a considerable encumbrance. Christians were not allowed to ride on horses; they might only travel on mules and asses. For the smallest disobedience they were put to death often in the cruellest manner. Their leader had suffered crucifixion; therefore that seemed a suitable punishment for those who followed him.

Pilgrims who made the journey to and from Jerusalem came back with stories of the terrible degradation that Christians were being made to suffer. Indignation came to a head when a certain French monk returned from a visit to Jerusalem. He became known as Peter the Hermit. Of small stature and almost fragile frame, his glowing spirit of determination was apparent to all who beheld him. It was his mission, he believed, to bring the Holy City into Christian hands. He travelled all over Europe, barefooted, clad in an old woollen tunic and serge cloak; living on what he could find by the wayside and what was given him; and he roused the indignation of the whole of Europe over the need to free Jerusalem from the infidel.

It happened that in the year 1095 Pope Urban II was at Clermont in Auvergne presiding over a gathering of archbishops, bishops, abbots and other members of the clergy. People from all over Europe had come to hear him speak; Urban had been very impressed by the mission which Peter the Hermit had been carrying out and asked him to come to him. On the steps of the church, in the presence of the Pope, Peter told the assembly of the fate meted out to Christians in the Holy Land by the ruthless infidels who were eager to eliminate Christianity.

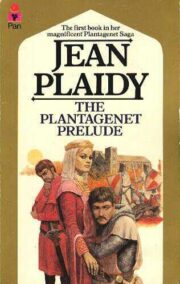

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.