He picked up a copy - there were three - and the Archbishop of York took another.

He mounted his horse and with his small company about him, he rode to Winchester. He despised himself. He had gone too far along the road to placating the King. He should never have taken the oath in public; he should never have agreed to it in private. He should have led his weaker brethren. He should have defied the King, inviting death. What mattered it if he were done to death? All that mattered was that he should be faithful to God and the Church.

He could hear the members of his suite discussing the Constitution.

‘What could he have done?’ asked one. ‘If he had defied the King more openly it would have been the end for us all.’

‘Yet has he not endangered the liberties of the Church?’ asked another.

His standard-bearer, a Welshman of an impetuous nature, cried out suddenly, ‘Iniquity rages through the land. No one is safe who loves the truth. Now that the chief has fallen, who will stand?’

‘To whom do you refer?’ asked Thomas.

‘To you,’ answered the Welshman. ‘You, my lord, who have betrayed your conscience and your fame and the Church. You have acted in a manner which is hateful to God and against justice. You have joined with the ministers of Satan to overthrow the Church.’

‘Oh God of Heaven, you are right,’ cried Thomas. ‘I have brought the Church into slavery. I came not from the cloister but from the Court, not from the school of Christ but from Caesar’s service. I have been proud and vain. I have been foolish. I see that I have been deserted by God and am only fit to be cast out of the Holy See.’

His Archdeacon rode up beside him.

‘My lord,’ he said, ‘if you have fallen low, rise up bravely. Be cautious and strong and the Lord will help you. Did He not make David great and was he not an adulterer and a murderer? Did not Peter deny Him thrice and was he not the founder of His Church? You have been Saul and now you are Paul. You know what you must do. The Lord will help you do it.’

‘You are right, my friend,’ said Thomas. ‘I will start again. God will be beside me and never again will I fall so low. I will die for the Church if need be.’

There seemed to be only one thing Thomas could do. He must see the Pope. He must tell him everything that had happened and ask what he must do next. The King’s edict was that no one should leave the country without his consent. Even so he must get away. The King had ignored him but he would not continue to do so. Thomas knew that Henry was trying to shift the power from Canterbury to York for he was aware that in Roger there was a man of immense ambition as well as an enemy of Thomas Becket.

Thomas disguised himself as a wandering monk and with a few members of his suite rode to Romney where he had arranged that a boat should be waiting for him.

He reached the coast without mishap but so violent a wind had blown up that he was forced to abandon the project.

He could not remain at Romney but must return to Canterbury, and this he did. But he intended to try again in a clement season, and one day when the weather was mild he set out again.

His servants, believing that he had now reached France, were afraid to stay in his palace and with the exception of one cleric and his boy servant, they left.

They talked awhile of the sad fate of the Archbishop and how the man, who many had said had ruled the King, for when he was Chancellor the King had loved him dearly, was now fallen so low, the lower for having risen so high.

‘Ah, my boy, it is a lesson to us all,’ said the cleric. ‘Now go and make sure the doors are shut and bolted that we may sleep safely this night. In the morning we must depart, for it will not be long before the King’s men arrive. They will take away all the worldly goods of the Archbishop for the King would despoil him not only of his office but of his goods as well.’

The boy took a lantern and went to do his master’s bidding, and as he came into the courtyard in order to close the outer door he saw a figure slumped against the wall. He held the lantern high and peered. Then he let out a shriek and ran to his master.

‘I have seen a ghost,’ he cried. ‘The Archbishop is dead and has come to haunt the place.’

The cleric took the lantern and went to see for himself.

He found no ghost but Thomas himself.

‘My lord,’ he said, ‘you are back then?’

‘The sailors who were to take the boat across to France recognised me,’ said Thomas. ‘They would not sail, so fearful were they of the King’s wrath. I see that God does not wish me to escape.’

If this were so then he must try other methods. It occurred to him that if he could see Henry, if he could talk reasonably, if he could remind him of their past friendship they might yet come to an understanding.

He asked for a meeting and somewhat to his surprise the King, who was at Woodstock, agreed to see him.

Henry was in a mellow mood. He had spent a few days in the company of Rosamund and their two children, and these sojourns always had a softening effect on him.

When Henry saw Thomas he noticed how wan he had become.

‘You’ve aged,’ he said. ‘You are not the merry reveller you once were.’

‘Nor are you, my lord King, the friend who joined in our fun.’

‘We have had our differences,’ answered Henry, ‘and alas they persist. Why did you attempt to leave the country? Is there not room here for us both?’

Thomas looked at the King sadly, but Henry would not meet his gaze.

The King went on: ‘Why have you asked for this audience? What have you to say to me?’

‘I had hoped, my lord, that you might have something to say to me.’

‘There is much I would say to you, but first there is one thing that you must say to me. Have you come to your senses, Becket?’

‘If you mean by that have I come to sign and seal the Constitution I can only say nay.’

‘Then go,’ cried the King. ‘There is nothing else I want to hear from you.’

‘I had hoped for the sake of the past …’

‘By God’s eyes, man, will you obey my orders or will you not? Go! Get from my sight. I will hear one thing from you and one only.’

Thomas came sorrowing away.

The Queen had followed the conflict between Becket and Henry with some interest. It amused her to recall how great their friendship had been and how there was a time when Henry preferred that man’s company to anyone else’s. It was strange to think that she had been jealous of Becket. Who would be jealous of him now? Poor broken old man. If she were not so pleased by his downfall she could be sorry for him.

She was forty-two years of age now - still a beautiful woman, still able to attract men, or so her troubadours implied. They still sang songs to her and she did not feel that they flattered her overmuch.

Since her marriage with Henry she had not wanted any other man, which was strange when she considered how he angered her; but then perhaps it was because he did anger her that she found his company so stimulating.

Now when they talked together of Becket, she did not say to him as his mother had done, ‘I told you so.’ She let him pour out his disappointment in that man and fed his anger against him. It brought them nearer together.

She often wondered how many mistresses he had scattered about the country. As long as there were several of them it was not really important. The only thing she would not tolerate was if there was one who specially took his fancy.

But no! She was sure this was not so. And the fact that she could talk to him of the exigencies of Thomas Becket certainly brought them closer together.

They were passionate lovers at this time, almost as they had been in the early days of their marriage. It was intriguing that his hatred of Becket was driving him into her bed.

He would lie awake sometimes and talk about him. He would tell her little incidents from the past which she had never heard before. How he had often tried to tempt Becket to indiscretions with women and never succeeded.

‘You didn’t try hard enough,’ she told him.

‘But I did. I even sought to trap him. But not he. I don’t believe he ever slept with a woman in his life.’

‘What sort of a man is he?’

‘Oh, manly enough. He can ride and hawk with the best. He is skilled in all the arts of chivalry.’

‘And where could a rustic learn such things?’

‘He was always an appealing fellow. Some knight taught him these things when he was quite a boy.’

‘He is a schemer. He wormed his way into Theobald’s good graces. I believe the Archbishop of York could tell you some stories.’

‘I never liked that fellow. Though he’d be loyal to me rather than to Thomas. He’s ambitious. I thought Thomas was, but he’s changed.’

‘You should not allow him to flout you.’

‘He is Archbishop of Canterbury. He would have to resign of his own volition.’

‘You should make it impossible for him to cling to office.’

‘How so?’

‘Is it beyond your powers? You know a good deal of how he lived when he was constantly in your company. There must have been something you could bring against him.’

The King’s eyes shone. ‘I will do it,’ he said. ‘I will find something from Roger of York, and John the Marshall will surely contrive something.’

‘Then do this, for I do assure you that that man is determined to plague you and while he is Archbishop of Canterbury you will not be true King of England. Could you bear now to hear of something other than the affairs of your Thomas Becket? Then listen to me. I am pregnant again.’

The King expressed his pleasure. He would welcome an addition to the nursery. A girl or a boy. He would not mind which.

All the same his mind was still on Thomas Becket.

As Eleanor said, it was easy. John the Marshall some time before had claimed the manor of Pagham which was on one of the archiepiscopal estates. The case which had been tried in the Archbishop’s court had been decided in Thomas’s favour. Now he could have the case re-tried in the King’s court and accordingly a summons to attend was sent to the Archbishop.

After his meeting with the King, Thomas had grown so sick at heart that he had become ill and had had to take to his bed. He was therefore unable to obey the summons and sent four of his knights to the court in his place.

This gave John the Marshall a chance. To ignore a summons to court showed a contempt of it and this was a crime.

Thomas was ordered to appear before a council at Northampton to answer the accusation. When he approached Northampton a rider met him with the news that the lodgings which were always at his disposal in that town had been given by the King to another member of the council; he must therefore find his own shelter.

Thomas saw then that the King was determined to humiliate him, but fortunately he could go to the Saint Andrew’s Monastery. Still hoping to bring about a reconciliation, Thomas went to the castle to pay his respects to the King. Henry was at Mass when he arrived and Thomas was obliged to wait in the ante-room for the service to be over. When it was, Henry emerged, and as Thomas went forward ready to kiss his hand, if it were extended to him for this purpose, the King walked past him as though he did not see him.

This was indeed the end, thought Thomas. The King would neither receive nor listen to him. He was clearly bent on his destruction, and if Thomas would preserve his life he must get out of the country.

When the Council sat, Thomas was called to account for having held the King’s court in contempt. He explained that he had been ill and had sent his knights to stand in for him. This was not accepted and a fine of PS500 was imposed.

Then came another list of charges. PS300 was demanded for it was said he had received this as the warden of the castles of Berkhamstead and Eye. Thomas replied that he had spent this and more in repairs to the King’s palace of the Tower of London and far from having profited from any money he had received, he had spent far more in the King’s service.

Thomas’s heart was heavy for he saw that the King was determined to ruin him. He had cast back in his mind to the days of their friendship when the King had given him money that he might live in a manner similar to his own. Now he demanded that this money should be paid back. Moreover Thomas had received revenues from several bishoprics and abbeys and the sum mentioned was some 40,000 marks.

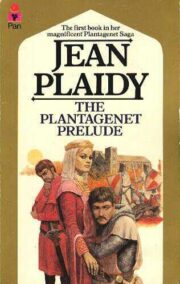

"The Plantagenet Prelude" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Plantagenet Prelude" друзьям в соцсетях.