In the family circle his father never behaved as though he were Prince of Wales; he would take his sons fishing on the banks of the Thames; and they played cricket in the Cliveden meadows. The Prince was very good at tennis and baseball, and he enjoyed playing with his own children. Lord Bute would join in the games; he was so good that he was a rival to the Prince; and the Princess Augusta would sit watching them with a little group of ladies, applauding when any of the children did well – and also applauding for the Prince and Lord Bute. George noticed that his mother applauded even more enthusiastically for Lord Bute than for the Prince of Wales.

George preferred being at Cliveden rather than Leicester House; as for those rare occasions when he was commanded to wait on the King, he dreaded them. His grandfather was an old ogre – a little red-faced man who shouted and swore at everyone and insisted on everyone’s speaking French or German because he hated England and the English, it seemed. The old man was a rogue and a tyrant. Papa and Mamma hated him, so, of course, George did too.

But even at Cliveden there were lessons to be learned, and now he must attend to this stupid affair of the waterman.

Edward was looking out of the window. Clearly he would not help. So George sighed, and after a great deal of cogitation he came up with the answer.

‘It’s thirty-six,’ he told Edward.

‘Sure?’ asked his brother.

‘I have checked it.’

Edward nodded and wrote down the answer.

George picked up the next problem but at that moment the door opened. Eagerly the boys looked up from their work; but it was not one of their parents nor Uncle Bute. It was their true uncle, the Duke of Cumberland, their father’s younger brother.

Edward was delighted by the diversion, George to see his uncle. They saw little of him, and George presumed it was because he was on the King’s side, which he concluded judiciously, was what one would expect in view of the fact that he was the King’s son.

The Duke of Cumberland was dressed for hunting – a large man inclined to corpulence, at the moment beaming with affection.

‘I was hunting in the district and thought I’d come and see my nephews.’ He embraced George first, then Edward.

Come to see his nephews! thought George. Not his brother or his sister-in-law?

‘Papa and Mamma are here,’ said George.

‘Not in the house,’ replied their uncle. ‘Doubtless in that theatre of theirs with my Lord Bute.’

George detected a certain contempt in Uncle Cumberland’s voice. He hoped Papa would not come in and quarrel with him. He hated quarrels.

‘And here are you boys sitting over your books on a sunny day like this.’

‘It’s a shame,’ agreed Edward.

‘We have to learn our lessons,’ George reminded him primly.

Uncle Cumberland pulled up a chair and sat down heavily. He laughed. ‘What do you learn, eh? What’s that?’ He picked up the waterman problem and scowled at it. ‘Much good that’ll do you.’

‘Mr Scott thinks we should be proficient in mathematics.’

‘Well, I’m not a great mathematician like Mr Scott. I’m only a soldier.’

Edward had leaned his elbows on the table and was propping up his face as he stared intently at his uncle. ‘Mathematics are a bore,’ declared Edward. ‘So are French and German.’

‘Mr Fung does his best to teach us, but we are a trial to him,’ George explained.

‘I like dancing with Mr Ruperti,’ declared Edward.

‘But music is the best of all,’ put in George. ‘It is the only subject at which we seem to make much progress. Mr Desnoyer is pleased with us.’

The Duke sat smiling expansively at his nephews.

‘You boys should be learning to become soldiers, not prancing about with Mr Ruperti and scraping violins.’

‘We play the flute and the harpsichord,’ George explained.

‘You should learn how to command an army; you should study the niceties of strategy. Wouldn’t you like to be a general?’

Edward said he would, but George was silent. He hated the sight of blood and did not care to think of men dying. Dying was not a noble glorious thing; people did not merely fall down dead; they suffered. He hated to think of people’s suffering, and worst of all, himself suffering or inflicting it.

All the same Uncle Cumberland was a fascinating figure and as they rarely saw their relations from the King’s Court a visit like this was an event.

He was a good talker and even made war sound fascinating. He drew his chair up to the table and said he would explain to them what had happened at a certain battle, the result of which had put their family firmly on the throne.

‘For, nephews,’ he said, ‘we came within danger of losing the throne. Your grandfather was ready to fly to Hanover; he had his valuables packed, and with his friends was ready to leave. And the rebels had come as far as Derby.’

‘To Hanover!’ cried Edward. ‘Do you mean, Uncle, that the people would have sent us away?’

‘Aye, sent us packing and put the Stuarts back on the throne. Our enemy the King of France had sent Bonnie Prince Charlie over to drive us away, and they were as far as Derby. Think of that. All the way from Scotland. Here, where are your maps? Now, I’ll show you. This is where the rebels were. It was November. I advanced to Stone, hoping to meet them. They were soon on the retreat.’

His big hands were on the maps; his voice was low and intense; he glorified war himself, and his very single-mindedness fascinated the boys.

‘Now…’ The hand, big, brown, powerful, ranged over the map. ‘I drove’em back here… right to Penrith… right over the border. This had taken time and it was now December. I attempted to cut them off at this point, but there were too many for us. I had good men…’ His face softened. George could believe that he had good men. He would see that they caught his enthusiasm, his passion for war. It was apparent as he talked that this was a man who would know no fear… and no mercy. His eyes glowed; he was reliving that occasion all over again, and George had the impression that he was hoping the Pretender would come back or that someone else would give him an opportunity to save the crown for the House of Hanover.

‘We were all that winter in Scotland,’ he said. ‘Can’t do battle in the winter, boys. It’s cold up there. Spring’s the best time for battle. But there are bigger problems for a commander than battle. Ah yes. How’s he going to feed his men? How’s he going to get them where he wants? That’s the nightmare, boys. The battle… that’s the glory.’

‘Many die…’ began George.

‘Do you know how many they lost at Culloden, boy?’

George shook his head.

‘Good God, and they’re supposed to be educating you! Two thousand rebels! And our losses? You must always set one beside the other. That’s how you calculate the extent of your victory. Three hundred and forty loyal English gentlemen lost their lives at Culloden, boys. But we got two thousand of them. It’ll be long before that scum raise a standard against our King, I can tell you.’

George was silent. ‘What is it, boy?’ demanded his uncle.

‘George doesn’t like people being hurt,’ explained Edward.

That made Uncle Cumberland rock with laughter. ‘So that’s the way they’re bringing you up, is it? Dance with Mr Ruperti! Music with Mr Desnoyer! French and German with Mr Fung! By God, what you boys want is to learn to be men. I’ll teach you a few things about living.’

‘But this is dying,’ interrupted George.

That made Uncle Cumberland laugh louder. In breathless tones he told the story of Culloden and how the bloody battle had gone. Even George was caught up in the excitement, and Cumberland looking from one to the other of the flushed faces was well pleased.

‘I’m going to get Sir Peircy Brett to tell you how he encountered the Elizabeth on the high seas. That’s a story well worth hearing. You’ll learn what it means to defend your country and that’s what you’ll have to do, boy, when you’re King, which will be one day. Now the Elizabeth . . . she was a French ship. She was convoying the small frigate with their Prince Charlie on board and she was carrying the ammunition. Sent by the King of France, boys, to defeat good Englishmen, he hoped. Much chance he had.’

‘When there was a Cumberland to defend us,’ cried Edward, and received a warm look of approval from his uncle.

‘And not only a Cumberland, boy. There are men like Peircy Brett in England too. He was in command of the Lion . . . sixty guns. Elizabeth she was a ship of twenty-four. And Lion sighted Elizabeth and went into the attack.’

‘And sank her?’ cried Edward.

‘Hey, wait a minute, boy. You want it too easy. It was a bloody battle…’ George saw the gleam in Uncle Cumberland’s eyes. ‘What slaughter! It was indeed a bloody battle. Lion was a wreck when it was over. Forty-five killed and one hundred and seven wounded.’

‘But that was our ship.’

‘Yes, you have your losses in battle. But Elizabeth was fit for nothing. She couldn’t go on. She had to limp back where she’d come from… and she was carrying supplies. So… their Bonnie Prince Charlie landed in Scotland, an impoverished adventurer… not the well-equipped young conqueror the King of France sent out. That’s battle, boys. That’s war. We lost Lion, but the purpose was achieved. I can tell you this: the loss of Elizabeth was as important to our victory as Culloden.’

George was thinking of the battle at sea; the shrieks of dying men; the blood… . there would be blood on the decks… on the cold cruel water. No, he did not like it, although he was fascinated.

‘I’ll get Brett to tell you the full story one of these days,’ went on Uncle Cumberland. ‘It’s a tale you boys should know. I’ll take you with me to camp. You, George, should know how to defend your crown. Now…’ He had pulled the map towards him. This was the map of Europe. He was going to tell more stories of battles and blood. This was living, he was thinking; the boys’ education was being neglected; battles were of more importance than hypothetical problems about non-existent watermen.’

He had the map spread out before him when the Prince and Princess of Wales came in accompanied by Lord Bute and Lady Middlesex.

‘Ha, ha, brother,’ cried Uncle Cumberland, getting up and kicking his chair back. ‘And my sister…’ He took Augusta’s hand and kissed it. George, watching, saw that his father was displeased and as his parents were always in agreement, so was his mother.

Cumberland ignored Lord Bute and ran his eyes swiftly over Lady Middlesex. He liked women; in fact, gambling and women were what he enjoyed next to making war; he had never married; and had no desire to; but that had nothing to do with his fondness for the opposite sex. Lady Middlesex he knew was a favourite of Fred’s – a clever woman but too short, too dumpy and her skin was as brown as a walnut; someone had once said she was as yellow as a November morning and by God, they were right. Fred, like his father and grandfather could not be said to choose his mistresses for their beauty.

‘We did not know that you were here,’ said Frederick mildly. He disliked his brother, but was too good-natured to show it. ‘We should have been advised.’

‘I wanted no ceremony. So I slipped into the schoolroom and gave my nephews a lesson.’

‘They look as if they’ve enjoyed it,’ said Lord Bute.

The Duke raised his eyebrows; he was surprised that an attendant should have expressed an opinion. He disliked the fellow in any case. He had heard he had a great influence with the Prince of Wales and that he accompanied them everywhere. The Prince commanded him to attend on the Princess while he enjoyed the company of Lady Archibald Hamilton, Lady Middlesex and Lady Huntingdon. It made a cosy foursome, a little bourgeois community. Frederick liked to live simply at Cliveden. It would have to be different when he ascended the throne, which Cumberland hoped would not be for a long time. Fred as King was a prospect which did not appeal to him.

Augusta was clearly pregnant, so Frederick was doing his duty in spite of the ladies. She looked well content with the arrangement, too. A stupid woman, thought Cumberland; but a docile one. She never raised her voice against Fred. She was very different from their mother. Cumberland was sad, thinking of the Queen’s death. She had doted on him and had done her best to have Fred passed over for him. He was the son both his father and mother would have liked to see mount the throne. But Fred was the eldest, and although his parents had done their best to keep him in Hanover and had not allowed him to come to England until he was twenty-one, he was Prince of Wales, and nothing was allowed to interfere with that.

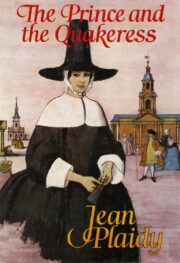

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.