‘Clothes are meant to keep the child warm, sister,’ said Uncle Henry, ‘not to adorn her.’

‘Oh yes, brother,’ Mary agreed fervently.

But as Hannah grew a little older she found a great pleasure in beautiful things and when one of the flower-sellers in the market gave her a rose she carried it up to her room and pinned it on her dress. Her great dark eyes seemed to glow more brightly; the pink of the flower toned perfectly with the grey cloth and seemed to bring out the delicate pink in Hannah’s own clear skin.

Uncle Henry cried out in dismay when she came down to dinner wearing the rose.

‘What is that thou art wearing, Hannah?’ he asked, and she thought that the devil must have changed the beautiful flower into a toad or something horrible since that was the only way she could account for Uncle Henry’s horror.

She looked down at it. ‘It… it is a rose… Uncle.’

‘A rose. And what is it doing there?’

‘It is just there… Uncle.’

‘How didst thou come by such a thing?’

She was bewildered. She had been so pleased to be given the rose; she enjoyed its scent; and the contrast of colour it made on her dress; she had felt happy wearing it. And now it seemed she had done a dreadful thing.

‘Old Sally the flower-seller gave it to me.’

‘Thou shouldst not have taken it.’

‘She wished it, Uncle.’

‘The place for flowers is in gardens. God put them there. He did not mean them to be worn for vanity.’

She had flushed and although she was unaware of this, her beauty was startling. It alarmed Uncle Henry as well as her mother. They would have preferred to see her insignificant.

‘Thou art guilty of vanity, niece,’ said Uncle Henry. ‘I think thy mother will agree with me.’

‘Indeed yes, Henry,’ whispered Mary Lightfoot.

‘This is a sin in the eyes of the Lord. Thou wilt go to thy room. Take off that flower. Give it to me… now…’

She felt the tears in her eyes. For a few seconds she hesitated, almost ready to defy him. Then she was aware of her mother’s terror; and she pictured them being turned out of this comfortable house… back to Wapping… the cold, cold room, the smell of boots and shoes… the smell of the river and the vague lightness of hunger. Then with trembling fingers she handed him the rose.

He took it and said to her in a voice that thundered with indignation so that she was reminded of Moses returning from the mountain to find his people worshipping the golden calf: ‘Go to thy room. Pray… pray long and sincerely for God’s help. Thou hast need of it.’

She walked slowly up the stairs. The feeling of sin weighing heavily on her.

In the cold room she knelt and prayed until her knees were sore. Then her mother came in and they prayed together.

When they rose from their knees and Hannah’s mother appeared to think she had gained God’s forgiveness for her wickedness, she ventured to say as though excusing herself: ‘But it was such a pretty rose.’

That gave Mary an opening for one of those lectures which were so much a part of Hannah’s upbringing.

‘Sin often comes in the guise of beauty. That is why it is so easy to fall into temptation.’

When she was alone Hannah would stand at the window and watch the ladies and gentlemen pass through the market on the way to the theatre. They were so beautiful but so sinful, for they wore more adornments than a single rose. Hannah feared it was probably sinful to watch such people. There was so much sin in the world that it seemed one must constantly be on the alert for it. There they were, the ladies in their Sedan chairs, and surely their complexions could not have been naturally so brilliant as they appeared; ornaments flashing in their hair; feathers, diamonds… What a load of sin they must carry on their persons if a simple rose could be so full of iniquity.

But how Hannah loved to watch them! Gentlemen with brocade coats and elegant wigs; footmen running ahead of their chairs to clear the way and while some in the crowd gaped at their magnificence others were too accustomed to the sight to pay much attention, unless it was a person of some note. Then the crowd would cheer or boo, however the mood took them; but they would almost always laugh. There seemed to be such a lot that was gay, amusing, interesting and such fun going on down there. Fun? It was sin. But Hannah was conscious of a quiet rebellion within her. If one sinned in ignorance could one be blamed? She thought not – at least it could not be quite so wicked to sin in ignorance. Therefore how much better it was to remain in ignorance.

She would tell no one of the pleasure she derived from looking down on the noisy excitement of St James’s Market.

Hannah was ten years old when Uncle Henry decided to marry. What consternation there was in the room she shared with her mother. Mary Lightfoot feared the cosy existence might be at an end. Henry was good to them; but what of Henry’s wife?

Five years of living comfortably – at least as comfortably as one could live in such close proximity with sin – had softened them. Mary was disturbed – not that she believed her brother would see her go hungry, he was too good a man for that; but a strange woman in the house would be sure to change something and Mary trembled for the future.

She need not have feared. Aunt Lydia proved a meek and docile wife – a true Quaker, a virtuous woman who would no more have thought of turning out her sister-in-law and her fatherless child than she would of taking a lover.

After the first mild difficulties of settling down Mary and Hannah adjusted themselves to the new régime. Uncle Henry was the head of the house – good but stern, anxious to care for those under his roof – his sister and her child, no less than his wife and his own children. The children began to arrive in due course; George three years after the wedding, Rebecca two years later, Henry two years after that and Hannah two years after Henry. Mary and her daughter Hannah soon found new ways of being useful in the house and Mary realized that their position was yearly becoming more secure. Hannah was nurse to the children; Mary helped her sister-in-law in the house. It proved to be a very satisfactory arrangement.

In spite of having three able-bodied women in the household Henry Wheeler could afford to employ a servant and he took into his household a young woman of Hannah’s age.

They called her Jane, and Jane’s coming made a great deal of difference to Hannah. Jane was not a Quaker; she liked to laugh and enjoy herself; she remarked to Hannah that she could see no harm in that. Neither could she for the life of her see why it should be more sinful to laugh than to look glum. Hannah listened half fearfully. Jane’s attitude to life was everything she had been taught to fear. Yet she did enjoy laughing with Jane when they were making the beds together or taking the children for their airings. Being so much older than her cousins – she was thirteen years older than George the eldest – meant that Hannah had no choice of a friend except Jane. So it was natural that they should be often together.

It was Jane who caught Hannah at the window. She was not in the least shocked; she came to join Hannah and pointed out the elaborate chair which was being carried through the market. Did Hannah know the gentleman who was being carried? Hannah did not know. Oh, but Hannah knew very little of the world because everyone should know the gentleman in the chair. It was Lord Bute himself. And they said that the Princess of Wales was very partial to him. Had Hannah ever heard that? Hannah had not and she thought that must make the gentleman very happy, which set Jane rocking with laughter.

‘It makes them both happy, so they say, Miss Hannah. But whether the Prince is so happy about it… that’s another matter. Not that he would complain, considering…’

Hannah was nonplussed and fascinated. It was interesting to learn from Jane that every household was not run like Henry Wheeler’s, and that there were scandals even in the royal family.

Jane was surprised by the ignorance of Hannah; and enjoyed enlightening her.

So Hannah began to learn something of the world outside a Quaker household and she could not help it if she were fascinated by it, and secretly she longed to be part of it. If Uncle Henry had had a house in the country where they never saw any life other than their own it would have been different; but it was not so. Here they were in the midst of a noisy, bustling, virile world and yet not of it. St James’s Market with its haggling and bargaining was a strange place for a Quaker to live; yet Quakers could be good businessmen and Uncle Henry was undoubtedly that, and if it was unsuitable in some ways it was profitable in others; for as far as trade was concerned it was an ideal spot. In the middle of the Market was the large Market House inside which were the butchers’ shambles and outside were the butchers’ stalls. Market-days were Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays; and on these days the noise of the buyers and sellers filled the house. Then there was The Mitre tavern to which even on those days when there was no market the people flocked in from St Martin-in-the-Fields.

It was not easy to turn one’s eyes away from the busy world when it was on one’s doorstep.

‘It’s no life for a girl, Miss Hannah,’ said Jane mournfully.

Hannah might tell of how Uncle Henry had rescued her and her mother from the dire poverty of Wapping, but Jane still insisted that it was no life for a girl. Better to be a servant-girl than the master’s niece, Jane reckoned. She wouldn’t change places with Miss Hannah. There was a mysterious person to whom she referred as Mr H. who was very interested indeed in Jane. At first Hannah had not believed in his existence; he was a dream figure, something to talk about when they were alone together; but it seemed that he was no phantom. Once when they were out with the children Jane took Hannah down Cockspur Street past Betts the glass-cutters and as they passed a young man slipped out and talked nervously to them.

It turned out that he was Mr H. and he was really ‘far gone’ on Jane.

On the way home Jane said it was a shame that Hannah had not got a beau. Yes, with her looks it was a crying shame.

And when she returned to St James’s Market Hannah surreptitiously looked into the mirror and could not help being pleased with what she saw there. She was a beauty. She only had to look at Jane’s pert and pretty face to know that she had something which the serving-girl lacked; and she felt a little sad to think of passing all her days in her uncle’s house making beds, looking after the children, and growing as old as her mother without ever having been part of the gay and bustling life which went on under her window every day and in particular on Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays.

There was great excitement when the King, the Prince and Princess of Wales and other members of the royal family were going to the theatre, the back door of which was in Market Lane; to reach this, the procession would have to cross the Market; and to see them a crowd would undoubtedly gather, for in view of the strained relations between the King and his elder son, it was rarely that they were all seen together.

Uncle Henry was disturbed. One never could be sure what the crowd would do. What if they became wild. ‘I think,’ he said, ‘we will take the linens out of the window. It will be better so.’

‘If the linens are taken out the children might perhaps sit in the window on our chairs to see the procession pass,’ suggested Lydia.

Uncle Henry considered this, but really he could see no harm in it.

As the children were growing excited at the prospect, Uncle Henry added a little homily about the worldliness of outward pomp and the difference between the shadow and the substance. But he believed they should be there because loyalty to the throne was something the children should be taught; and there were always intolerant people who could work up emotions about those whose opinions were different from their own.

Yes, they should all sit in the window and watch the royal procession to the theatre.

Hannah was delighted with an opportunity to enjoy something without secrecy.

Lydia had placed chairs in the window in place of the bales of linen. Little George and Rebecca were dancing up and down with excitement and Hannah put a finger to her lips to warn them lest their father decide that too much pleasure must indeed be a sin. Young Henry was clutching his mother’s skirts and Hannah’s mother was holding in her arms the newest arrival – Hannah after her cousin. Mary Lightfoot placed the chair for the master of the house and discreetly took her place at the back of the window.

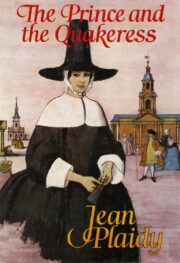

"The Prince and the Quakeress" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince and the Quakeress" друзьям в соцсетях.