“Nina,” Oscar cried, “I’m such a damn fool! The Bolsheviks won’t listen to anything I say anymore. As long as Trotsky was in charge, I could do what I liked, but now, they’re accusing me of taking currency out of the country illegally. And that was the deal in the first place!”

Nina’s heart sank. “But what about my exit papers? You told me you’d have no trouble getting hold of them for me.”

“There’s only one way I can take you out of the country,” said Oscar, looking mournfully at Nina. “You’ll have to marry me and sign a document giving me power of attorney. Then I can go to an American embassy somewhere in Europe on your behalf.”

Nina felt out of her depth. “But I can’t do that! I don’t have any papers.”

“We can sort out a Soviet passport for you,” Oscar promised. “I’ve arranged it already. The most important thing is to get an American visa and permission to leave the country from the OGPU.”

Nina asked Oscar to give her time to think.

In theory, she told herself, it would not be Nina Kupina who was getting married, but “Baroness Bremer.” And the marriage would not harm Shilo as it would not be legally binding for her. As for Klim, he would never find out. In any case, what was the point of tormenting herself over a marriage of convenience when she had already betrayed her real husband, and it was too late to do anything about it?

I’ll go back to Shanghai and start life afresh, Nina decided.

The next morning, she agreed to marry Reich and to sign over power of attorney to him.

It turned out that Klim had already left China for Moscow by the time Nina sent her telegrams, and that was why he had never answered any of them.

She could only imagine what he thought of her now. Klim could have forgiven her for just about anything—but not a marriage of convenience to another man.

After he had driven off, Nina had run back onto the platform to ask Oscar where he had met Klim, but Oscar did not remember.

“Take care!” he said, planting a kiss on Nina’s lips. “I’ll write to you soon.”

Nina returned to the deserted house on Petrovsky Lane and sank feebly onto the bench that stood in the hall by the front door.

What should she do now? How could she find Klim? Her head felt as if it was filled with wet sand.

She heard the flick of a light switch, and Theresa appeared at the top of the stairs.

“Oh, so you’re back already!” she said. “After you left, there was a call for Mr. Reich from Mr. Klim Rogov.”

Nina jumped to her feet. “Did he leave his number?”

Theresa went to where the telephone hung on the wall and picked up a large address book from the shelf beside it.

“Here you are, ma’am. Last time Mr. Rogov rang, he left his address and his telephone number.”

Her head spinning, Nina stared down at Theresa’s penciled scrawl. Klim lived in Chistye Prudy, only a fifteen minute drive away.

Nina took a cab to the building that housed the Moscow Savannah bookstore. She entered the small, inviting courtyard and mounted the porch, but seeing her shadow on the door, she froze.

Everything she was wearing, from her cloche hat to her extravagant fur coat, had been bought with Oscar’s money, and every bit of it was evidence of her crime. How could she appear before Klim in all this shameful finery?

Just then, the door flew open, and a red-haired man in an unbuttoned coat came out onto the porch.

“Is that you, Mrs. Reich?” he cried out delightedly. “Have you come to see me? Or is it Klim you’re after?”

“Have we met before?” asked Nina frowning.

“Of course. I’m Elkin. Don’t you remember me? I came to see your husband to discuss selling a car.”

Nina had no memory of Elkin. Oscar had always had a constant stream of visitors.

“I used to have a garage,” explained Elkin, “but I’ve packed it in now. I’m selling off all my stock.”

He reached into his pocket and fished out a torn visiting card. “Here’s my name and telephone number. Please, remember me to your husband!”

Nina nodded. “He’s abroad at the moment, but I’ll tell him when he comes back.”

She walked quickly past Elkin and made her way up the stairs to the story above.

There was a small landing, a round window, and a smart door with a brass handle in the shape of a comical giraffe.

Nina crossed herself quickly as if she were about to jump into a hole in the ice and pushed the doorbell.

After a few agonizing minutes, Klim appeared at the door. He was wearing a white shirt with the collar unbuttoned, a dark gray waistcoat, and trousers of the same color. His hair was shorter than Nina remembered it.

“Hello,” she said in a weak voice. “May I come in?”

Klim looked at her for a long time. “What do you want?”

“I want to talk.”

The door below banged shut, and they heard Elkin’s voice downstairs. “Please, don’t forget about my car!”

“Come in then,” Klim said shortly. Clearly, he did not want to start a domestic argument in front of his neighbor.

Nina took off her fur coat and began to unlace her overshoes. Klim made no move to help or show her where to hang her coat.

“Where’s our daughter?” she asked.

“Kitty’s not here.”

Nina followed Klim into a living room with colored glass in the windows. He showed her to the divan and sat down on the windowsill as far away from her as possible. He looked at her with cold surprise as if to say “How on earth did you find the cheek to show your face here?”

“I sent you quite a few telegrams,” Nina said. “I waited and waited for you to reply, but it seems you were right here in Moscow all the time.”

“If I’m not mistaken, we separated a year ago,” said Klim. “To tell you the truth, I have no desire to go raking around in the past. You have your life now, and I have mine.”

Nina felt herself grow cold. “But you followed me to Moscow—”

“I think you should leave now,” Klim interrupted.

“Won’t you at least listen to my side of the story? I’m not going anywhere until I’ve spoken to you!”

“If you won’t leave, I will.” Klim got to his feet. “When you get tired of talking to the wall, you can close the door after you.”

Klim left so quickly that Nina had no time to do anything to stop him. She stood in the middle of the room, crushed and miserable.

The day was coming to an end. The windows in Klim’s living room shone like the stained glass windows in a church, but the bronze giraffe heads that decorated the curious branched light-fitting had the look of malevolent imps in the half-light.

Nina walked around the apartment, scrutinizing every last detail. In the typewriter on Klim’s desk, there was an unfinished article in English, and files of newspapers, directories, and piles of telegraph forms were scattered everywhere. It looked as though Klim had found work in Moscow.

Clearly, he had plenty of friends. There was a globe in the corner of the room covered in signatures and good luck messages. And it seemed he had plenty of money too to judge by the freshly upholstered furniture and the expensive china in the cabinet.

Here and there, Nina came across some item Klim had brought to Moscow from Shanghai: the fountain pen she had bought for him in the Wing On department store, a pair of cuff links in the shape of scarab beetles, and a shirt with his initials embroidered on the cuffs. Looking at these things, she felt her heart turn over. Once, they had been as good as hers, but now, she did not even have the right to touch them.

She went into Kitty’s bedroom, and tears came into her eyes. Kitty must have grown a lot, judging by her new dresses and stockings. Her drawings hung all over the walls, and there were toy horses and giraffes strewn across the rug.

Kitty probably doesn’t even remember me, Nina thought bitterly. Little children have short memories after all.

There were two pairs of women’s shoes in the hall, but they were different sizes and clearly belonged to two different women. One was a pair of homemade felt sleepers, the other a pair of elegant leather shoes.

Nina rushed into the bathroom but was relieved to find only two toothbrushes there, one large and one small. There were no women’s clothes in the closets, but Nina found a nail file and a hairpin on the floor. It seemed unlikely that these things belonged to a servant who occupied the little room off the kitchen.

But there was another woman coming to see Klim regularly—she even kept a pair of indoor shoes there to wear around the house.

Nina sat down and buried her face in her hands. What if Klim had met somebody else?

It couldn’t be true, she thought. If so, he would never have been so angry or adopted such a hostile manner with her. Instead, he would have asked her how she was and probably even offered to help her in some way.

“Klim will calm down,” Nina said to herself, “and when he comes back, we’ll sit down and discuss everything like adults.”

Night fell, but he did not come. For minutes at a time, Nina would sit motionless in the armchair before jumping up and pacing the room, unable to bear it anymore. Why didn’t he come back? Where was Kitty? And where was the servant girl? If only someone would come!

Evidently, Klim had decided to spend the night somewhere else.

Nina found a blanket and a pillow, turned off the light, and lay down on the divan in the living room. Not long ago, Klim himself had slept there, and perhaps not only that.

At last, she heard the key turn slowly in the door. Her whole body stiffened, and she strained her ears to catch the slightest sound. The blanket fell to the floor, but Nina did not dare pick it up.

The door creaked, and she heard the sound of cautious footsteps.

“How about a nightcap?” she heard Elkin’s voice from the landing. “Do you have any of that brandy left?”

“Go to bed, for God’s sake, man!” she heard Klim say. “You’re drunk.”

“I’m no more drunk than you are, my dear fellow!”

Apparently, Klim had been sitting with his neighbor downstairs, waiting for Nina to leave.

All was quiet out in the hall. Then at last, Klim came into the living room, bent over, and ripped the telephone cord out of the wall. Then he stood for a long time without saying a word, gazing at Nina.

A minute passed; two minutes; three. Nina was afraid to breathe.

Klim picked up the blanket that had fallen to the floor and carefully put it over her.

Feeling a pang of overwhelming tenderness, Nina touched his hand, but Klim grabbed her wrist and squeezed it so hard that she screamed in pain. “What are you doing? Let me go!”

His fingers continued to press on her wrist as if he wanted to break it.

“Stop!” she cried. “You’re hurting me!”

He flung down her hand and left the room. Nina heard the door of Kitty’s bedroom slam shut.

She ran out into the dark corridor and felt her way along the walls to the other room.

“Please, open up!”

There was no reply.

Nina hammered at the door panel with all her strength. “We need to talk! Klim, open up! I won’t leave till you’ve heard what I have to say.”

“Stop making a scene!” she heard Klim snap. “It’s three o’clock in the morning.”

“You can’t hide from me forever!”

At last, the door opened, the light switch clicked, and a flood of bright light dazzled Nina for a moment.

Klim stood staring at her with icy rage. “Do you realize I have to go to work tomorrow? I didn’t ask you to come here and have a fit of hysterics.”

“But I didn’t—”

“Go to bed now, or I’ll put you out of the house! Good night.”

The door slammed again.

Nina’s head was throbbing from all the tears she had cried.

He’s just drunk, she told herself. He doesn’t want to hear anything just now. But I’ll explain. Tomorrow, I’ll tell him everything.

Nina managed to drift into a light sleep just before dawn. She dreamed that she was trying to cross a deep river in a small rowing boat full of holes. But with every stroke of the oars, the boat sank deeper in the water. She was in some silent, misty, deserted place, and she knew she would never reach the other side.

Nina woke from a loud rattling sound as if somebody had dropped something in the kitchen. Apparently, Klim was already up.

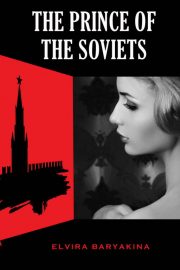

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.