“How could a creature like that have survived in Soviet Russia?” he keeps saying.

Elkin is touched by the fact that Nina is elegant and well-dressed like the young ladies in Moscow before the revolution, and that she doesn’t mangle her Russian with fashionable abbreviations.

“Brains, Mr. Rogov! Brains—that’s the most important thing in a woman! Well, apart from all the rest.”

I try to interrupt his enthusiastic outpourings, but he is unstoppable.

“I don’t mean to say I’m making a play for her,” Elkin says. “I’m no match for her millionaire husband. All the same, a healthy man can’t stop thinking about these things. And don’t come over all ‘holier than thou’ with me! You’re just a hypocrite, whereas I tell it like it is. You know her, don’t you?”

“No,” I say. “And I have no intention of getting to know her.”

“But I saw her go into your apartment that day. Sour grapes, is that it? Easy on the eye, but not so easy to catch?”

I am doing my best to ensure that Nina catches neither my eye nor Kitty’s. I have ordered Afrikan to make a new gate in the fence in the yard behind the house, and now, we go out by this exit. I’ve also asked him to keep the gates locked so that unauthorized people (Nina that is) cannot come in to our stairwell.

I don’t know what she is thinking. Is she bored without her husband perhaps? Is that why she’s decided to play games with me? Or is it Kitty she’s interested in? Maybe she’s waiting for a good moment to take her away?

Galina is also puzzled. She asked me, “Did you know that that woman who visited you is working in Elkin’s store?”

I told her I wasn’t interested in gossip about the neighbors. However, this did nothing to reassure her. In fact, Galina has now begun to suspect me of being “unfaithful” to her. Every day, she asks Kapitolina where I’ve been while Galina was out and listens at the door when I’m on the telephone.

This has been going on for a few weeks now, and I’m living in a permanent state of tension. I pray that Nina will leave me alone, although this request to the heavenly powers seems utterly ridiculous since we never see one another and she doesn’t interfere in my life.

The problem is me. I know Nina is somewhere nearby, and this thought is enough to drive me out of my senses.

What should I do? I can’t leave Elkin’s house any more than I can forbid Nina to come to the Moscow Savannah. The only thing I can do is to ask Galina to take my child when I go out to meetings. At least then, Kitty will not see Nina.

Tata is a bad influence on Kitty, of course, but at least it’s the lesser of two evils.

16. THE RAID

Vadik, the Pioneer leader, promised Tata that if she took an active part in public service, she would be able to join the Pioneers that summer and go on a camping expedition.

Tata had never been anywhere in her life except Moscow and only to places within walking distance of her home. Her mother never gave her any money for the tram.

But a Pioneer camping expedition was a real adventure! The children would pile into an open truck, drive through the streets singing songs, and then set off with their backpacks far away into the unknown—perhaps even as far as the Moscow suburbs.

Tata was already in agonies of joy and suspense.

She registered on a three-person team or troika on a state-wide project to stamp out illiteracy, taking the place of a boy who had recently come down with tuberculosis. The members of the troika were to go around the neighborhood recruiting adults who could not read and write for literacy classes.

The thought of knocking on strangers’ doors terrified Tata, but she told Julia and Inessa, the other members of the troika, that she was shivering from cold rather than fear and embarrassment. It was twenty degrees below outside.

Tata had a warm hat knitted with yarn from an unraveled old sweater, but her coat was a pitiful sight. It had been made from a plush mat decorated with squirrels. These squirrels were the cause of merciless taunting from her classmates.

The troika expedition was a disaster from the start. In the first building they went to, they were met with crude insults. In the next, they were stopped by a fierce dog in the yard. In the third, a maid told them to wait while she went to the store for kerosene, and they sat for two hours on the stairs for nothing. When the maid came back, she was visited by a fireman, and the shameless couple began kissing in front of the children.

Julia dug Tata in the ribs. “Say something!”

“Do you know that in 1920, six hundred and forty-five Russians out of every thousand couldn’t read?” began Tata, stammering. “And now the figure is only four hundred and fifty-six.”

“And do you know when you’re not wanted?” barked the fireman and stamped his foot at the girls.

The troika fled outside.

“It’s all your fault!” Julia said and gave Tata a cuff around the head.

It was getting dark over the boulevard, and the sound of a brass band could be heard from behind the trees. Despite the cold weather, the rink on Chistye Prudy was crowded with skaters.

“What do you think? Shall we keep going?” asked Tata, her teeth chattering.

“She said she wasn’t afraid to go ‘round houses on her own,” said Julia to her friend. “Didn’t she?”

“Yes, she did!” Inessa nodded.

Tata was taken aback. “What do you mean ‘on my own’? Vadik said that the three of us should work as a team.”

“She’s a ‘fraidy cat,’” snorted Inessa scornfully. “When we go camping, she’ll probably start crying for her mommy.”

“I’m not afraid!” Tata protested. “I can go ‘round houses on my own!”

“Well, let’s see you do it then,” taunted Julia. “Do you see that house with the turret? Go and find out if there’s anyone living there who can’t read or write.”

There was nothing for it. Hunching miserably, Tata shuffled toward her doom.

At the gate, Tata was met by a man with a ginger toothbrush mustache.

“I know just the person you need,” he said,\ when Tata told him she was looking for anybody who could not read and write. “Come with me.”

He took her across the yard and shown her the entrance door. “Go up one flight of stairs,” he said. “There’s only one apartment. It’s impossible to miss.”

Tata felt like a terrible fool. Luckily, she had a piece of paper with a speech on it, dictated by Julia. Without it, she would have been unable to say a word.

She reached the apartment, rang the doorbell, and when the door opened, she began to read aloud, unable to look the tenant in the eyes.

“Good afternoon, Comrade Tenant!” she said, struggling to decipher her own scribbles. “We are re-pre-sen-ta-tives from the troika of… oh, well, never mind that now…. What’s your profession?”

She looked up and froze.

“My profession? Journalist,” said Uncle Klim, smiling down at her.

“Can you read and write?” Tata heard herself saying in a small voice.

“Of course not!” came a voice from the staircase. It was the man with the ginger mustache. “Mr. Rogov, I sent this young lady up to you on purpose, so she could teach you to read and do your sums.”

Tata wished the ground would swallow her up.

“I’m sorry,” she said, blushing. “I just wanted to know if anybody here needed help learning the alphabet.”

At that moment, Kitty came rushing out. “Here you are!” she cried delightedly, hugging Tata.

“Won’t you come in?” suggested Uncle Klim.

Mother will hit the roof when she finds out I came to see the Rogovs without permission, though Tata helplessly. Nevertheless, she entered the apartment.

“I’ll just come in for a minute to warm up,” she said.

As soon as she stepped inside, Tata realized that Uncle Klim was no revolutionary; he was a bourgeois. His home was a bastion of materialism—there was a mirror, a grand piano, and pictures of some fancy wenches on the walls. With a father like that, no wonder Kitty had some gaps in her education.

Uncle Klim brought in a samovar from the kitchen.

“Kapitolina isn’t here, so we’ll have to fend for ourselves,” he said. He put down a dish of candy on the table. “Help yourself.”

Tata gasped. Her mother always squirreled away sweets, and only once in a blue moon would she nibble on a toffee, letting Tata have half.

Tata reached out her hand to the dish, but at that moment, she remembered how all the children at school had been urged to eat only the right candies—the ones in ideologically sound wrappers which were called things like “Internationale,” “Republican,” or “Lives of the Peasants Then and Now.”

But all Uncle Klim had were candies, their wrappers decorated with a picture of a girl bobbing a curtsey.

Tata looked at Kitty who had already put a candy in her mouth.

“How many can I have?” she asked, despising herself for her lack of character.

“As many as you like,” Uncle Klim said.

Tata drank some delicious tea, ate candies and cookies, and began to feel that she was developing bourgeois tendencies.

“Let’s see what books you have,” she said, looking at Klim’s bookshelves. “Anna Karenina, poetry… some sentimental rubbish! That’s harmful literature. Self-indulgent drivel.”

Uncle Klim looked at her with unfeigned curiosity. “So, what reading do you consider good for the soul?”

“There’s no such thing as a soul,” snapped Tata. Then she added, not entirely truthfully, “I’m interested in politics, not fiction. At the moment, our class is reading Lenin’s speech to the third Young Communist Congress. I don’t suppose you’ve ever inoculated yourself with the germ of revolution.”

Uncle Klim burst out laughing and said that he would write down that phrase in his notebook; it would be useful for one of his articles. This ought to have pleased Tata; after all, it isn’t every day adults want to make a note of your words. But she had an uneasy feeling the conversation was not going well.

“Come on. I want to show you something!” said Kitty, and, grabbing Tata by the hand, she led her into the other room.

Tata was amazed to see that Kitty had a bedroom to herself, and more toys than Tata had ever seen in her life. Kitty reached under the bed, brought out a colored magazine with a picture of a bourgeois lady on the cover, and settled down on the rug.

“Let’s play. You can be her, and I’ll be her.”

One picture in the magazine showed the beach and some scantily clad girls, the other—a bride and groom at a wedding table laden with cakes.

“Let’s eat all those!” said Kitty, beaming. “Yum-yum!”

Tata decided to take charge. She announced that they would play at a communist wedding.

“I’ll be the secretary of a Young Communist organization, and you can be a worker bride who is getting married to… how about this teddy bear?”

Kitty shook her head. “No, he’s too young for me. We bought him yesterday.”

Tata spent a long time trying to pick out a potential husband: Kitty’s rag horse, a wooden duck on wheels, and a progressive worker from the Liberated Labor factory whose portrait was in the paper. Eventually, Kitty agreed to marry a giraffe painted on her bedroom wall.

Tata read out a report about the new way of life in the Soviet Union and presented the newlyweds with a blanket from the women’s union and a pillow from the factory management.

Uncle Klim knocked at the door. “Tata, I’ve been called out on business urgently. Would you mind staying here with Kitty?”

“Of course not,” she said.

He pulled on his coat. “I’ll be back in a couple of hours. Be good!”

“We will,” promised Tata, a brilliant plan already taking shape in her head.

About thirty journalists were crowded into the press room. They sat around a long table, typewriters at the ready.

“What can it be at this time of night?” muttered Seibert irritably, yawning.

“I expect they’ve signed yet another report on the unbreakable alliance between the USSR and Afghanistan,” replied Klim. He was sure they had all been brought here for nothing, for some story that presented no interest whatsoever to the world’s news agencies.

Still, the journalists allowed themselves to dream of larger-than-life heroes and dangerous villains.

“We really are a bunch of vultures,” said Seibert, looking around at his colleagues. “We feed off battles, plagues, and disasters. The more dead bodies, the happier we are.”

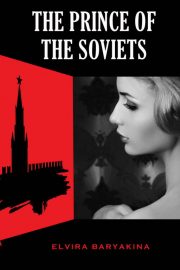

"The Prince of the Soviets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Prince of the Soviets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Prince of the Soviets" друзьям в соцсетях.