Coigny was charming, seeming old to me, being about thirty-eight years old; but his manners were exquisite and I was no longer so stupid as to believe that no one over thirty should come to Court. Then there was the Prince de Ligne, a poet, and the Comte d’Esterhazy, a Hungarian whom I felt justified in seeing because my mother had recommended him. There were also the Baron de Besenval and the Comte d’Adhemar, the Due de Lauzan, and Marquis de La Fayette, who was very young, tall and redheaded and whom I christened Blondinet.

All these people congregated in Gabrielle’s apartments and there I went to them to escape the stifling strain of etiquette in the petits appartements.

It was the Princesse de Lamballe who brought Rose Bertin to my notice.

The Duchesse de Chartres also recommended her. She was a grande couturiere with a shop in Rue Saint-Honore and was considered extremely clever.

As soon as she was brought to me she went into ecstasies about my figure, my colouring, my daintiness and natural elegance. All she needed to make her happy was to dress me. She brought with her some of the most exquisite materials I had ever seen in my life, and draped them around me, scarcely asking permission to do so. In fact she was completely lacking in that respect which I was accustomed to receive and she behaved as though dressmaking was of more importance than the Monarchy. I was not so much a Queen as a perfect model for her creations. She made me a gown which I thought the most elegant I had ever had. I told her so and the next day she had ‘discovered’ another material which was created for me; no one else should have it; if I did not, she would throw it aside. She would make up this material for no one but the Queen of France.

I was amused by her. She never waited in the anterooms but came straight in to my apartments. When one of my attendants referred to her as a dressmaker she was shocked.

I am an artist !’ she retorted.

And she was. She fascinated me with her talk of silks and brocades and colours; she came to me regularly with designs, and sometimes I would make a suggestion. If Madame had not been the Queen of Prance she would have been an artist! Now she must be content to show these masterpieces to the world I’ My clothes were becoming more and more elegant. There was no doubt about that. My sisters-in-law tried to copy me. Rose Berth would laugh secretly in my apartments.

“Have they the figures of Aphrodite? Do they walk as though on a cloud? Have they the grace and the charm of an angel?”

They had not, but they were rich enough to be allowed to make use of Rose Benin’s talents.

Between us she and I set the fashion of the Court. Whenever I entered a room everyone waited breathlessly to see what I was wearing. Then they would go to Rose Benin and beg her to copy it.

She chose her clients with care, she told me. This one was too thin, that one too fat, another completely ungainly.

“What do you think, Madame, a merchant’s wife had the impertinence to call at my establishment yesterday. Would I work for her? The arrogance. Although she was a very rich merchant’s wife, I said, ” I have not time to spare to talk to you, Madame. I have an appointment with Her Majesty”.”

It added a new interest to life; and when the bills came in I scarcely looked at the large figures at the bottom of the paper.

I just scrawled “Payes’ on the bottom.

Rose Benin was very contented with me—and I with her.

Oh, the folly of those days I I refused to see what was going on in the world about me. I did not listen when people talked of France’s uneasy relationship with England which might break into war at any moment. I had completely forgotten the guerre des farines. I danced until three or four in the morning, or played cards, and I was beginning to gamble heavily now.

I had done a great deal to abolish etiquette but I had naturally not been completely successful. When I awakened, one of my attendants would bring to my bed an album in which patterns of my dresses had been fixed. As soon as a new dress arrived this would be fixed into the album. My first task on awaking was to decide what I would wear for the whole of the day, and because of that I must have an account of all my engagements perhaps a reception in the morning, neglige for afternoon, and a sumptuous Benin gown for evening. Another attendant would stand by the bed holding a tray of pins, and when I had made my choice I would stick one of these into the elect. When I had made my choice the album would be taken away, the dresses brought out in readiness for when they would be needed.

The ceremony of getting up was tiresome. I thought longingly of the Trianon and determined to spend as much time there as possible. To awake in my own link room. What joy that was! To leap out of bed and look at my gardens which I was having made to my designs. Perhaps to run out with a robe thrown over my night attire. What fun, what joy to feel the dew on the cool grass with my bare feet. That was one of the joys at the Trianon.

How different from Versailles, where etiquette seemed to suffocate me and rob me of my natural vitality.

One winter’s morning my lever was carried to excess. To dress me I must have a lady of honour on one side and a tire woman on the other; and as if this was not enough my first femme de chambre must be in attendance besides two of the lower servants.

It was a lengthy business and on that cold morning I did not relish this. It was the tire-woman’s duty to put on my petticoat and hand me my gown and the lady of honour’s to perform the more intimate tasks of putting on my under clothes and pouring out the water in which I should wash. But when a Princess of the Royal Family was there, the lady of honour must allow her to give me my linen; and this had to be most scrupulously observed, because there might be occasions when two or three Princesses were present and if one usurped the duty of the other, thereby implying she was of higher rank, this would be a major breach of etiquette.

On this particular day I was undressed waiting for my undergarments to be handed to me and was just about to take them from the maid of honour when the door opened and the Duchesse d’Orleans came in. Seeing what was happening she took off her gloves and, receiving the garment from the maid of honour, handed it to me; but at that moment the Comtesse de Provence appeared.

I sighed deeply, my irritation rising. There was I without my clothes, already delayed by the Duchesse d’Orleans, and now here was my sister-in-law, who would be deeply affronted if anyone but herself put on my clothes. I handed her the garment, folded my hands across my breasts and, with an expression of resignation, waited, grateful for only one thing:

there could not be a lady of higher rank than my sister-in-law to come and repeat this stupid performance.

Marie Josephe, seeing my impatience and that I was cold, did not stop to remove her gloves but put the shift over my head and knocked my cap off while doing so.

I could not contain myself.

“Disgraceful!” I muttered.

“How tiresome!”

Then I laughed to hide my irritation; but I was more determined than ever to put my foot through their silly etiquette. I understood that it was probably necessary on certain state occasions, but to carry it to these lengths was quite ridiculous.

Thus I revelled in bringing Rose Benin into my private apartments where no tradesman had been admitted before. And I spent more and more time at the Trianon.

The really great ceremony of the day was that of dressing my hair.

Naturally I employed the best hairdresser in Paris, which probably meant in the world. Monsieur Leonard was as important a personage in his way as Rose Bertin was in hers. Every morning he drove to Versailles from his establishment in Paris to dress my hair, and people used to come out to watch him in his splendid carriage drawn by six horses. No wonder there was growing discontent about my extravagance. As Rose Bertin invented new fashions for me alone, he invented new hair styles. My high forehead had been a cause of complaint years before, but now styles were worn to suit high foreheads, and hair styles gradually became more and more fantastic.

The hair was stiffened with pomades and made to stand straight up from the head then padded with hair of the same colour; as far up as eighteen inches from the forehead. Monsieur Leonard would then begin his original creation. He would create fruit, birds, even ships and landscape scenes with artificial flowers and ribbons.

My appearance was a constant topic of conversation throughout Versailles and Paris; it was written and joked about, while my extravagances were deplored.

Mercy, of course, was reporting; but my mother did not need him, to learn about this.

She wrote reprovingly:

I cannot refrain from commenting on a subject which many newspapers have brought to my notice. I mean your manner of hairdressing. I gather that from the roots on the forehead it rises as much as three feet and on top of that are feathers and ribbons. “

I replied that the lofty head-dresses were fashionable and that no one in the world thought them in the least strange.

She wrote back:

“I have always held that it is well to be in the fashion but one should never be outre in one’s dress. Surely a good-looking Queen, blessed with charm, has no need of such foolishness. Simplicity of attire enhances these gifts, and is much more suitable to exalted rank. Since as Queen you set the fashion, all the world will follow you when you do these foolish things. But I, who love my little Queen and watch her every footstep, must not hesitate to warn her of her frivolity.”

There was a different tone in my mother’s letters these days. She warned; she did not command; and constantly she was telling me that she advised me through her great love for me.

I should have paid more attention to her; but it was so long since I had seen her, and even her influence was beginning to wane. I no longer trembled at the sight of her handwriting; after all, if she was an Empress, I was the Queen—and the Queen of France. I was a woman now and could act as I pleased. I Continued to consult with Rose Benin; my dress bills were of enormous proportions and my hair styles grew more preposterous each day.

Moreover Artois and his cousin Chartres were encouraging me to gamble. We played faro, at which it was possible to lose a great deal of money. The money which the King gave me to pay my debts each week all seemed to go at the gambling table.

I had no sense of money; all I had to do was scribble “Payez’ on the bills which were presented to me and let my servants deal with the matter.

My husband was too indulgent. I think he understood that driving passion not to be bored, not to stop and think, and blamed himself for it. Always he must have been conscious of the shadow of the scalpel which he could not bring himself to face. He paid my debts and never lectured me; but he did try to curtail the gambling not for me only, but for the whole Court.

But what excited me more than anything more than clothes, gambling, dancing and hair styles were diamonds. How I loved those gorgeous sparkling stones; and they became me as no others did. They were cold yet full of fire; and I was too. I never once allowed a young man to be alone with me; I was frigid, it was said; but beneath the frigidity there was a brilliant fire which like a diamond could flash in certain circumstances.

I had many jewels some I had brought from Austria, and then there was the casket my grandfather had given me for a wedding present but a new jewel could always fascinate me. If the people grumbled at my extravagance, at least the tradespeople were delighted. The Court jewellers, Boehmer and Bassenge, who had come to France from Germany, were as delighted with me as Rose Bertin and Leonard were. They would present their beautifully-set stones to me, looking so delicious in their satin-and-velvet cases that I found them altogether irresistible. When they showed me a pair of diamond bracelets I was fascinated by them and I did not think of the price until I had decided I must have them.

This brought protests from my mother. I hear that you have bought bracelets which have cost two hundred and fifty thousand livres, with the result that you have thrown your finances into disorder and are in debt. This deeply disturbs me, particularly when I con template the future. A Queen degrades herself by decking herself out in this ostentatious manner, and still more so by lack of thrift. I know how extravagant you can be, and I cannot keep quiet about this matter because I love you too well to flatter you. Do not lose through your frivolous behaviour the good name you acquired when you arrived in France. It is well known that the King is not extravagant, so blame will rest on you. I hope I shall not live to see the disaster that will ensue unless you change your ways. ” The warning continued, for news of my gambling debts bad reached her.

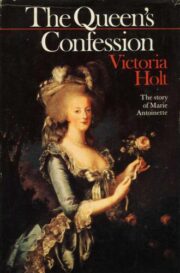

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.