But although Axel and I were not alone together we did enjoy many conversations. He made me see his affectionate mother; his father, for whom he had a deep respect and who, he admitted, was a little parsimonious and wondered when his son was going to give up wandering about Europe and settle down to a career. He even told me of Mademoiselle Leyel, a Swedish girl who lived in London and to whom he had been sent to pay court.

“Her vast fortune greatly appealed to my family,” he said gravely.

“And to you?” I asked.

I am not averse to a large fortune “And she is beautiful?”

“She is reckoned so.”

“I am interested in your adventure in London. Tell me more.”

“I was a guest in her parents’ luxurious mansion.”

“That must have been most pleasant.”

No,” he said.

“No. ” But why not? “

“Because I was an unenthusiastic wooer.”

“You surprise me.”

“Surely not. I was pursued by a dream. Something happened to me once years before … in Paris. In the Opera House there.”

I was afraid to speak to him for I was very much aware of my two sisters-in-law silently watching.

“Ah I And did you not ask for her hand?”

“I asked her. It was my father’s wish, and mine to please him.”

“So you are to marry this rich and handsome woman?”

“By no means. She refused me.”

“Refused you?”

“Your Majesty sounds incredulous. She was wise. She sensed my inadequacies.”

I laughed lightheartedly.

“We should not have cared for you to go to London … so soon. You have only just arrived in Paris.”

And so the days passed. Great events were happening to us but I paid no heed to that. It was only later that I gave them a thought.

Throughout the Court the conflict between England and her colonists in America, was being talked of and with great glee, because it delighted all Frenchmen to see their old enemies the English in trouble. Although in Paris English habits were followed slavishly there was an inherent hatred for our neighbours on the other side of the Channel.

Frenchmen could not forget the defeats and humiliations of the Seven Years War and all they had lost through that to the English; and ever since 1775, at the beginning of our reign, we had been applauding the Americans; in fact there were many Frenchmen who believed that France should declare war on England. Some time before, I remember my husband’s telling me that if we declared war on England it was very likely that this might bring a reconciliation between England and her colonies; after all, they were all English and they might well stick together if a foreign power attacked. Louis never wanted war.

“If I went to war,” he said, “I could not do my people all the good I wished.”

Nevertheless when America declared Independence on July 4th 1776 we were delighted and wished the settlers well. I remember three American deputies coming to France at that time; Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane and Arthur Lee. How solemn they were! How Sombre with their suits of cloth and their unpowdered hair. They stood out oddly among our exquisite dandies, but they were received everywhere and were quite the fashion and when the Marquis de La Fayette left for America to support the colonists many Frenchmen followed him. They were pressing the King to declare war, but Louis continued to stand out against it although we sent help secretly to America in the form of arms, ammunition and even money. At this time, however, the battle between our Belle Poule and the British Arethusa occurred, and Louis was reluctantly obliged to declare war against England—at least at sea.

I had listened to what Axel had told me about the American fight for independence; he was a fervent supporter of freedom; and I repeated his arguments to my husband. It was one of those rare occasions when I interested myself in state affairs.

Louis was anxious to please me at this time, and I do believe my voice, added to that of the others, was to some extent instrumental in bringing him to the decision to declare war at sea.

I was wildly enthusiastic for the Americans against the English; but when someone asked my brother Joseph for his opinion, he answered: “I am a Royalist by profession.” Mercy repeated this remark to me; it was a warning, reminding me that I was giving wholehearted support to those who were rebelling against Monarchy. The rights or wrongs of the dispute were neither here nor there. Kings and Queens who believed it was right and proper for subjects to rebel against them in any circumstances—were they taking a risk? It seemed my brother Joseph thought so; and he was more experienced than I. The weather during that summer was very hot and I began to feel my pregnancy. Unable to take much exercise I liked to sit on the terrace in the cool of evening often by the light of the moon or in starlight.

We had had the terrace illuminated with fairy lights and an orchestra played every night in the orangerie. The public were allowed to walk about freely in the gardens and they made full use of this-particularly during the warm summer evenings.

I and my sisters-in-law would sit on the terrace together and for these occasions we always wore simple white gowns perhaps of muslin and cambric and big straw hats with light veils over them to shield our faces. Thus we were often unrecognised and now and then people would sit beside us and talk to us without knowing who we were.

This of course resulted now and then in unpleasant incidents A young man came and sat beside me once in the gloom and made advances. I had spoken to him without realising his intentions and had to get up and walk abruptly away for he had made it clear that he knew he was speaking to the Queen.

Such incidents were extremely unpleasant, particularly as my sisters-in-law were nearby and would probably report, perhaps to the aunts, who now criticised everything I did and made much of every little happening, or to the Sardinian Ambassador, who would be pleased to embellish the story and spread it abroad. It was sure to be said that I encouraged amorous strangers. They were making up the most scandalous stories about me now; in fact it seemed to be a favourite pastime.

I decided as the autumn came that I would retire more and more from the public. I had every reason for doing so. So I kept more and more to my own apartments surrounded only by my most intimate friends like my dearest Madame de Polignac, the Princess de Lamballe and the Princesse Elisabeth, who as she grew older was becoming more and more close to me.

Axel de Fersen was frequently at my gatherings; we sang, played music and talked. They were very pleasant days. As for my husband, he was in a state of constant anxiety and I would laugh at him, for ten times a day he would come to my apartments to ask anxiously how I was feeling; and when he was not asking me he was summoning the doctors and accoucheurs demanding to know that everything was as it should be.

The ordeal of birth! It stays with me now. For any woman, giving birth to her first child is a frightening, though, I admit, exalting, experience. But with a Queen it is all that and a public spectacle at the same time. I might be giving birth to the heir of France, and therefore all France had a right to see me do it.

The town of Versailles was full of sightseers. It had been impossible to get a room anywhere since the first week of December. Prices shot up. Well what could one expect? They were all determined to see me give birth to my child.

It was a cold December day the 18th, I remember well when my pains started. Immediately all the bells of the town started to ring to let everyone know that I was in labour. The Princesse de Lamballe and my ladies-in-waiting hurried to my bedchamber; my husband came in some consternation. Our marriage had been such a topic of conversation for so many years that he feared there would be even greater interest than there usually was over a royal birth. He himself fastened the great tapestry screens about my bed with cords.

“So,” he said, ‘that they should not be easily overthrown. ” How right he was to take this action! When he had done this he dispatched guardsmen to Paris and Saint-Cloud to summon all the Princes of the Blood Royal, who, tradition demanded, should be present at the birth.

No sooner had the Princes arrived than the spectators stormed the chateau and many of them forced their way into the bedchamber. An effort, I gather, was made to prevent too many entering the room, but there were at least fifty people all determined to see a Queen in labour.

My pains were growing more and more frequent. I tried to console myself; this was the moment for which I had longed all my life; this was becoming a mother.

I had arranged with the Princesse de Lamballe that she should let me know, without speaking, the sex of my child, and I was aware of her close to my bed during the agonising hours that followed. The heat was tremendous for the windows had been caulked up to keep out the cold night air; but we had not bargained for such a crowded lying-in chamber. Packed close together so that there was no room for anyone to pass between them, some standing on benches to get a better view, leaning heavily against the tapestry screens so that, but for my husband’s foresight in using those thick cords, they would have collapsed on to the bed, the spectators whispered together. I felt I could not breathe;

I was grappling not only with the ordeal of birth but with the fight for breath. The smell of vinegar and essences mingled with that of sweating bodies and the heat was unbearable.

All through the night I fought to give birth to my child . and for my life; and at half past eleven on the morning of December 19th my child was born.

I lay back exhausted; but I must know whether the child was a boy. I looked at the Princesse; she was near the bed; she shook her head, in the arranged signal.

A girl! I felt a sick disappointment . and then . I was fighting for my breath.

I was aware of faces about me . a sea of faces . those of the Princesse de Lamballe, the accoucheur, the King.

Someone shouted: “My God, give her air. For God’s sake move away ..and give her air. “

Then I fell into unconsciousness.

I heard from Madame Campan afterwards what happened. None of the women could force their way through the crowds to bring the hot water. Air was absolutely necessary, for all the doctors agreed I was on the point of death by suffocation.

“Clear the room!” shouted the accoucheur. But the people refused to move. They had come to see the show and it was not yet over.

“Open the windows! For God’s sake open the windows!”

But the windows had been pasted all round with strips of paper and it would take hours to remove it that they might be opened.

There were moments in my husband’s life when he was indeed a King among men, and this was one of them. He pushed his way through the crowd and with a strength which no one would have thought possible in one man, he wrenched open the windows and the cold fresh air rushed into the room.

The accoucheur told the surgeon that I must be bled immediately, without hot water since it was unobtainable, and an incision was immediately made in my foot. Madame Cam-pan told me afterwards that as the blood streamed forth I opened my eyes and they all knew that my life had been saved.

Poor Lamballe fainted—as might have been expected-and had to be carried out; the King ordered that the room be cleared of all spectators, but even then some of them refused to go and the valets de chambres and the pages had to drag them out by their collars.

But I was alive, I had given birth to a child—albeit a daughter.

When I was conscious of what was going on I was aware of the bandage about my foot, and I asked why it was there.

The King came to my bedside and told me what had happened. Everyone seemed to be weeping and embracing each other.

“They are rejoicing,” he told me, ‘because you have recovered. We feared . “

But he could not go on. After a pause he said: “It shall never happen again. I swear it.”

The child . ” I said.

And the King nodded. The child was brought to me and laid in my arms;

and from the moment I saw her, I loved her and I would not have had her different in any way.

My happiness was complete.

“Poor little one,” I said, ‘you may not be what we wished for, but you are not on that account less dear to me. A son would have been rather the property of the State; you shall be mine. You shall have my undivided care, shall share all my happiness and console me in my troubles. “

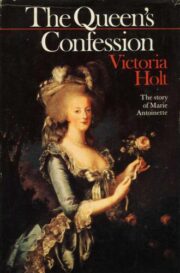

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.