It became clear soon that he was quite unaccustomed to living in palaces, and although our Schonbrunn and Hofburg would not compare with Versailles, or the other chateaux and palaces of France, he betrayed quite clearly that it was very grand in his eyes. He had been brought up in a village where his father had been a doctor and his brother an accoucheur; he himself had become a priest and would never have reached his present position but for the patronage of the Archbishop.

Aware of this desire to please not only my mother but me, I was quite content to study with the Abbe. We read together and studied for an hour each day which he said was enough because he knew that was all I could endure without becoming bored and irritated. Much later when I talked about those days with Madame Campan, who by then was more than first lady of the bedchamber and had become a friend, she pointed out the harm Vermond had done. But she disliked him and she thought he had a share of the blame for every thing that happened to us. Instead of reading together in our lighthearted way, and his allowing me to break off and give imitations of various people of the Court of whom some remark would remind me, I should have been given a thorough grounding not only in French literature but in the manners and customs of that land. I should, she said, have been made ready for the Court of which I was to be a part. I should have been made to study throughout the day if necessary (no matter how unpopular that made Monsieur Vermond); I should have been taught something of French history and of the people of France; I should have learned something about the rumbling dissatisfaction which long before I went there was making itself felt.

But dear Campan was a natural bos bleu and she hated Vermond and loved me; moreover, she was desperately anxious for me at that time.

So although I had to substitute a priest for my actors, the exchange was not so bad after all; and the daily hour with Vermond went pleasantly enough.

But I was not left alone. My appearance was under continual discussion. Why? I wondered, thinking of Joseph’s wife with the dumpy figure and the red spots. I had a good complexion, fine and delicately coloured; my hair was abundant; some said it was golden, some russet, some red. Blonde cendre, the French were to call it; and in the shops of Paris they would display gold-coloured silk and call it chevetix de la Reme. But my high forehead caused a great deal of consternation. My mother was disturbed because Prince Starhemburg, our ambassador in France, reported:

“This trifling imperfection might appear considerable at a time when high foreheads are no longer in fashion.”

I would sit before the mirror contemplating this offending forehead which I had not before noticed was different from other people’s; and very soon Monsieur Larsenneur arrived from Paris. He clucked over my hair, frowned at my fore head and went to work. He tried all sorts of styles and eventually decided that if my hair were dressed in a high pile straight up from my forehead, the latter would appear to be low in comparison with the hair. So it was pulled so tightly that it hurt, and was held in place by false hair, my own colour. To my disgust I was obliged to wear it like that, and as soon as Monsieur Larsenneur had gone I used to loosen the pins. Some of my mother’s courtiers thought it unbecoming, but old Baron Neny said that when I reached Versailles all the ladies would dress their hair ‘a la Dauphine’. Remarks like that always gave me an uneasy twinge because they implied that the great change was coming nearer and nearer; and I was trying hard to forget this in all the excitement of new hairstyles and dancing steps, and luring Abbe Vermond from the book we were reading to give imitations of people at Court.

My teeth gave cause for concern too, because they were uneven. A dentist was sent from France and he looked at them and frowned, as Monsieur Larsenneur had over my hair. He was always pushing my teeth about but I don’t think he made much difference and eventually he gave up. They were a little prominent, which, as they said, made my lower lip look ‘disdainful,” I tried smiling, which, although it exposed the uneven teeth, did abolish the disdain.

I had to wear stays, which I hated, and to grow accustomed to high heels, which prevented my running about the gardens with my dogs. When I thought of leaving the dogs I would burst into tears and the Abbe would comfort me by saying that when I was Dauphine I should have as many French dogs as I desired.

As my fourteenth birthday approached my mother decided that there should be a fete over which I should preside. The whole Court was going to attend, and it was to be a test to discover whether I was capable of being the centre of such an occasion.

This did not greatly alarm me. It was lessons which I could not endure. So without a qualm I received the guests and danced as Noverre had taught me. I knew I was a success, because even Kaunitz, who had come solely to watch me and not to be entertained, said so. My mother told me afterwards that he had remarked: “The Archduchess will do well in spite of her childishness, providing no one spoils her.”

The words my mother emphasised were childishness and spoils. I must grow up quickly, she insisted. I must not believe that everyone would do as I wished merely because I smiled.

The time was passing. In two months, providing all the arrangements had been made and all the disagreements between the French and the Austrians settled, I was to leave for France. My mother was deeply disturbed. I was so unprepared, she said. I was summoned to her salon and told that I should sleep in her bedroom so that she could find spare moments now and then to give me her attention. I was far more horrified by this immediate prospect than by the all-important one of starting a new life in a new country which was an indication of my character.

I still remember nostalgically now those days and nights of utter discomfort and apprehension. The big state bedroom was icy; all windows were wide open to let in the fresh air; the snow fluttered into the room, but that was not so bad as the bitter wind. We were all supposed to have our windows open but in my room I would persuade my servants to close them. They were willing enough as long as they were opened again before it could be discovered that they had been shut. But there was no such comfort in my mother’s bedroom.

The only warm place was in bed; and sometimes I would pretend to be asleep when she stood over me, pulling the clothes from my face, and it was all I could do to stop myself wincing from the icy draught.

With cold fingers she would move the hair out of my eyes, and she would kiss me very tenderly so that I almost forgot I was pretending to be asleep and would want to jump up and throw my aims about her neck.

Only now can I understand how anxious she was for me. I believe I became her favourite daughter not only because I had been my father’s, but because I was small, naive, impossible to educate, and . vulnerable. I realised later that she was continually asking herself what would become of me. I thank God that she did not live long enough to find out.

I could not always pretend to be asleep, and there were long dialogues, or rather monologues, in which I was instructed what I must do. I remember one of them.

“Don’t be too curious. This is a matter on which I am very concerned for you. Avoid familiarities with subordinates. “

“Yes, Mamma. “

“Monsieur and Madame de Noailles have been chosen by the King of France to be your guardians. You will always ask them if you are in any doubt as to what you should do. Insist that they warn you of what you should know. And don’t be ashamed to ask for advice. “

“No, Mamma. “

“Do nothing without consulting those in authority first. ” I found my thoughts straying. Monsieur and Madame de Noailles. What were they like? I started building up incongruous images in my mind which would make me want to smile. My mother saw the smile and was half exasperated, half tender. She took me in her arms and held me against her.

“Oh, my darling child, what will become of you? ” It would all be so different there, she said. There was a vast difference between the French and the Austrians. The French believed that everyone who was not French was a barbarian.

“You must be as a Frenchwoman, for you will be a Frenchwoman. You will be the Dauphine of Prance and in time Queen. But do not show eagerness for that. The King would detect it and naturally be displeased.”

She said nothing about the Dauphin who was to be my husband, so I did not think of him either. It was all the King, the Due de Choiseui, the Marquis de Durfort, Prince Starhem burg and the Comte de Mercy-Argenteau all those important men who had taken their minds from state affairs to think about Me. But then I had become a matter of state the most important they had ever had to deal with. It was so incongruous that I wanted to laugh at it.

At the beginning of every month,” said my mother, ” I shall send a messenger to Paris. In the meantime you can prepare your letters so that they can be given to the messengers and brought to me at once.

Destroy my letters. This will enable me to write to you more frankly.”

I nodded earnestly. It seemed so very exciting like one of the games

Ferdinand and Max used to like to play. I saw myself receiving my mother’s letters, reading them and hiding them in some secret place until I could bum them.

“Antoinette, you are not attending I’ My mother sighed. It was a reproach I constantly heard.

“Say nothing about domestic affairs here.”

I nodded again. No! I must not tell them how Caroline had cried, how she had declared the King of Naples to be ugly; what Maria Amalia had said about the boy she had, been sent out to marry; how Joseph had hated his second wife and how his first had loved Maria Christina. I must forget all that. ‘a “Speak of your family with truth and moderation.” H Should I speak of these matters if I were asked? I was pondering this but my mother went on: “Always say your prayers on rising and say them on your knees. Read from a spiritual book every day. Hear Mass every day and with-l draw for meditation when you are able.”

“Yes, Mamma.” I was determined to try to do all she said.

“Do not read any book or pamphlet without the consent of your confessor. Don’t listen to gossip, and don’t favour anyone.”

One had one’s friends, of course. I could not help liking some people better than others and when I liked them I wanted to give them things.

It went on endlessly. You must do this. You must not do that. And I shivered as I listened, for although the weather f was improving as we came nearer to April it was still cold in the bedroom.

“You must learn how to refuse favours—that is very important. Always answer gracefully if you have to refuse something. But most of all never be ashamed to ask for advice.”

“No, Mamma.”

Then I would escape perhaps to the Abbe Vermond for my lesson, which was not so bad, or to the hairdresser, who pulled my hair, or to my dancing lesson, which was sheer joy. There was an understanding between Monsieur Noverre and me that we would forget the time; we would be surprised when a servant came to tell us that Monsieur l”Abbe was waiting for me, or the hairdresser, or that I must be ready for my interview with Prince von Kaunitz in ten minutes’ time.

“We were absorbed in the lesson,” he would say, as though by referring to that delightful exercise as a lesson he excused us.

You are fond of dancing, my child,” my mother said in the cold bedroom.

“Yes, Mamma.”

And Monsieur Noverre tells me you make excellent progress. Ah, if only you were as well advanced in all your studies. ” I would show her a new step and she would smile and say I did it prettily.

“Dancing is after all a necessary accomplishment. But do not forget that we are not here for our own pleasure. Pleasures are given by God as a relief.”

A relief? A relief from what? Here was another suggestion that life was a tragedy. I started thinking about poor Caroline but my mother brought me out of my reverie with:

“Do nothing contrary to the customs of France, and never quote what is done here.”

“No, Mamma.”

“And never imply that we do something better in Vienna than they do in France. Never suggest that anything we do here should be imitated there. Nothing can exasperate more. You must learn to admire everything French.”

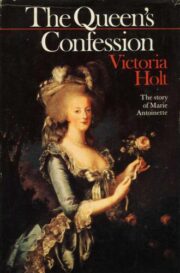

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.