Mirabeau, the strength behind the Third Estate, then announced that the National Assembly would only give way at the point of the bayonet, while Jean Sylvain Bailly, the President of the National Assembly, added that the nation once assembled could be dismissed by no one.

And the nation had assembled. That was what we did not realise soon enough. The Due d’Orleans, who had added his voice to that of the Third Estate, had been spreading sedition in the Palais Royale and was encouraging agitators. Each day there were meetings; new pamphlets were appearing several times a day.

The words Liberty and the People had a magic quality. There was an air of tension through Versailles and the whole of Paris.

And there was fear everywhere. We could not guess what would happen next. Axel spoke to me; he said: You know that I shall always be here if I am wanted. ” And I felt happier than I had for some time.

Perhaps he, as a foreigner, one who mingled with the people of Paris, understood the situation far more than we could. We did not believe that the Monarchy was tottering; we could not conceive it; but he had mingled with those crowds in the Palais Royale, he had heard the mutterings of the people.

It was necessary for Louis to go to Paris to attend a meeting of the States-General and I was worried as to what would happen there. I could not forgive Necker for not accompanying him. The man was annoyed because the King would not take his advice, and although I had asked him specially to be with the King, be had failed to do so.

Louis’s great quality was his courage. I never saw fear in him as in most men. If he took the wrong action which he did so often it was never through fear. Now that he had decided to be firm I knew that if someone could put up a good argument in favour of changing that firmness he would waver again. His trouble was that he must listen, be must see all angles of a situation, and there were too many in every case.

At the Assembly he made a firm declaration. He would not allow any changes of institutions, by which he meant the Army. He would make taxation equal; the nobility and the clergy should resign their privileges. He wished advice as to bow to abolish lettres de cachet.

When he left he ordered that the Assembly should be disbanded for the night, but no one obeyed the order. And when the Master of Ceremonies, the Marquis de Breze, announced the meeting closed and advised all to go home, Mirabeau stood up and shouted that they would go when they wished, and as for Breze, he could go back to those who sent him; and he repeated that only by the use of bayonets could they be separated.

But how typical of Louis to lose firmness as quickly as he had put it on. When Breze reported to him, he merely shrugged his shoulders and said: “Very well. Let them stay where they are.”

Then be made a mistake. He dismissed Necker and called in de Breteuil to take his place.

I was with die children reading to them aloud from the fables of La Fontaine. My daughter leaned against my chair following the text as I read and my son sat in my lap watching my lips and every now and then he would shriek with laughter as some phase of the story struck him as particularly funny.

It was easy at moments like these to forget what was happening all about us.

We were at the Trianon, which seemed to have changed its character in the last year or so. The theatre remained shut. I had no heart for it.

Often I would wander through the gardens with Gabrielle and we would try not to speak of the fears that were in our hearts. I was no longer surrounded by gay young men. They had been robbed of those sinecures which they bad all sought and which I had delighted to bestow upon them. They were a little sullen. We shall all be bankrupt,” was their cry.

I had stopped reading and dosed the book.

I wish to show you my flowers,” said Louis Charles And so we went out into the garden to that little patch which I had given him all for his own—for he delighted in flowers, and already, with the help of the gardeners, was cultivating them.

“Flowers and soldiers, Maman,” he had said, “I do not know which I love best.”

And hand in hand we walked out into the gardens and my dear villagers of the Hameau came out to curtsy and adore my children with their eyes; and no one would have guessed what was happening in the outside world. And yet again the Trianon was my haven.

My son released my hand and ran on ahead.

He reached his garden and stood waiting for us. I have been talking to a grasshopper,” he said.

“He’s been laughing at an old ant. But he won’t laugh, will be. Ataman, when the winter comes.”

When did you speak to the grasshopper, my love? “

“Just now. You couldn’t see him. He ran out of the book while you were reading.”

He looked at me seriously.

“You are making that up,” said his sister.

But he swore he wasn’t.

“I take my oath,” he said.

I laughed. But his way of exaggerating did disturb me a little. It was not that he did not mean to be truthful;

he had such a vivid imagination.

Then he was picking flowers and presenting them to me and his sister.

“Maman,” he said, ‘when you go to a ball I will make you a necklace of flowers. “

“Will you, darling?”

“A beautiful, beautiful one. It’ll be better than a diamond necklace.”

Always close to me were the warning shadows.

I picked him up suddenly and kissed him fiercely.

Td far rather have the flowers,” I said.

I heard news of what was happening in Paris. During those hot July days it seemed as though the city was preparing itself, waiting. I heard the names of dangerous men mentioned often, Mirabeau, Robespierre, Danton, and the biggest traitor of them all, Orleans—Prince of the Royal House-who was urging the country to rise against us.

“What does he hope for?” I demanded of Louis. To step into your shoes? “

“It would be impossible,” replied my husband. But I heard that crowds were thronging to the gardens of the Palais Royale day and night and that Orleans was already king of this little territory. The journalist agitator Camille Desmoulins was in his pay, it was said. These men were working against us.

They can never succeed against the throne,” said Louis. Madame Campan was quiet and more serious than ever. Tell me everything,” I said.

“Hold nothing back from me.”

There have been riots in Paris, Madame. Mobs are roaming the streets and the shopkeepers are barricading their shops. “

“Violence!” I muttered.

“How I hate it ” Danton speaks in the Palais Royale gardens, so does Desmoulins. They have discarded the green cockade because those are the colours of the Comte d’Artois. “

“I fear they hate Artois almost as much as they do me.”

I was sad, remembering those extravagant adventures we bad shared.

“They have chosen the colours of Monsieur d’Orleans, Madame—red, white and blue, the tricolour. They are asking for the recall of Necker. They parade through the streets with busts of Necker and the Due d’Orleans.”

“So they are heroes now.”

Louis had changed again. He now decided that firm action was needed.

He would call out the military; he would send garrisons to the Bastille. The States-General must be disbanded. And while garrisoning the Bastille the King gave orders that the guns were not to be used against the people.

I shall never forget that night of the fourteenth of July. The hot sultry day was over and we had retired to our apartments.

I was unable to sleep. How different from Louis. His rest seemed never to be disturbed. He had to be aroused when the messenger came.

It was the Due de la Rochefoucauld de Liancourt riding in haste from Paris with a terrible tale to tell. His face was ashen, his voice trembled.

I heard him calling to be taken to the King and I rose and wrapped a gown about me.

The King’s servants were arguing. The King was in bed. He could not be disturbed at this hour!

And Liancourt’s terse answer: “Awaken the King. I must see the King.”

The Due was in the bedchamber.

“Sire!” he cried.

“The people have stormed the Bastille I’ Louis sat up in bed rubbing the sleep from his eyes.

“The Bastille …” he murmured. “They have taken the Bastille, Sire.”

“But … the governor …”

“They have killed de Launay, Sire. They marched into the prison with his head on a pike.”

“This would seem to be a revolt,” said the King.

“No, Sire,” answered the Due gravely.

“It is a revolution.”

Friends Leave Versailles

Upon you I throw myself. It is my wish that I and the nation should be one, and in full reliance on the affection and fidelity of my subjects I have given orders to the troops to remove from Paris and Versailles.

The Queen then appeared on the balcony.

“Ah,” said the woman in the veil, ‘the Duchess is not with her?

“No,” replied the man, ‘but she is still at Versailles. She is working underground like a mole, but we shall know how to dig her out. ” … I thought it my duty to relate the dialogue of these two strangers to the Queen.

Goodbye, dearest of my friends. It is a dreadful and necessary word:

Goodbye.

The Terror was upon us.

Artois, white-lipped, all his gaiety gone, came to the apartment where the King and I were together.

“They are murdering people all over Paris,” he said.

“I have just heard that my name is high on their list of vicms.”

I ran to him and threw my arms about him. There had been a coldness between us lately, but he was my brother-in-law; we had once been good friends and there were so many memories of shared follies from those days when neither of us allowed any cares to disturb us.

“You must go away I’ I cried. I had a horrible picture of his head on a pike as poor de Launay’s had been.

“Yes,” said the King calmly. He was the only one among us who was calm.

“You must make your preparations to leave.” ;

I wondered about myself. How high was I on the list? Surely at the top of it.

Then I thought of those dear friends of mine Gabrielle, who had been the subject of so much scandal; my dear Princesse de Lamballe.

I said: “And there will be others.”

Artois read my thoughts, as he used to in the old days.

“They are talking of the Polignacs,” he said.

I turned away. I went to my private chamber and I sent Madame Campan to bring Gabrielle to me.

She came startled; I took her into my arms and embraced her warmly.

“My dearest friend,” I said, ‘you will have to go away. “

“You are sending me away?”

I nodded, “While there is time.”

And you? “

“I must be with the King.”

“And you think …”

“I do not think, Gabrielle. I dare not.”

“I could not go. I would not leave you. There are the children.”

“Are you like these rebels, then? Do you too forget that I am still the Queen? You will go, Gabrielle, because I say you shall.”

“And leave you?”

“And leave me,” I said, turning away, ‘because that is my wish. “

“No, no!” she cried.

“You cannot ask me to go! We have shared so much we must stay together. You would be happier if I stayed than if I went.”

“Happy! I sometimes think I shall never be happy again. But I could find more comfort in thinking of you safe far from here rather than to live in fear that they would do to you what they have done to de Launay. So begin to prepare at once. Artois is going. Everyone who can must go … and perhaps in time it will be our turn.”

With that I ran out of the room, for I could bear no more.

I went back to the King. Messengers had come from Paris. The people were demanding the presence of the King there. If he did not come they would march to Versailles to fetch him. They wanted him in Paris; they wanted to take ‘good care’ of him.

If you go you may not return,” I said.

I shall come back,” he answered, as calmly as though he were about to set out for a day’s hunting.

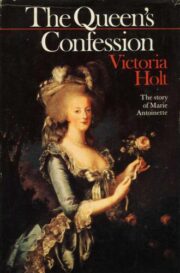

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.