But they bad never felt much rancour against the King. They rushed from the room and came to the Council Chamber, where I stood behind the table holding my children close to me.

A group of guards immediately placed themselves about the table.

They stared at me.

“That’s the one. That’s the Austrian Woman.”

The Dauphin was whimpering: the red cap was suffocating him. One of the guards saw my look and took the cap off the child’s head. The women protested but the soldier cried:

“Would you suffocate a harmless child?”

And the women for they were mostly women were ashamed and did not answer. I felt relieved then. I could feel my son clutching my skirt, hiding his face against me to shut out the horror of all this.

It was so hot; the crowded room was stifling. oh God,” I prayed.

“Let death, come quickly.”

I would welcome it, for if we all died together there could be no more suffering like this.

The soldiers had unsheathed their bayonets; the mob eyed them warily; but they were shouting obscenities about me; and I prayed again: “Oh God, close my children’s ears.” I could only hope that they did not understand.

A man who was carrying a toy gibbet from which hung a female doll approached the table. He chanted: “Antoinette i la lanterne.”

I held my head high and pretended not to see him.

One woman tried to spit at me.

“Whore !’ she cried.

“Vile woman.”

My daughter moved closer to me as though to protect me from this creature. My son clung tighter.

I looked into the woman’s face and said: “Have I ever done you any harm?”

“You have brought misery to the nation.”

Tou have been told so, but you have been deceived. As the wife of the King of France and the mother of the Dauphin I am a Frenchwoman. I shall never see my own country again. I can be happy or unhappy only in France. I was happy when you loved me. “

She was silent and I saw her lips moving; there were tears in her eyes.

I was aware, too, of the stillness about us. Everyone was quiet, listening to me as I spoke.

The woman looked at my child and lifted her eyes to me and said: “I ask pardon, Madame, I did not know you. But I see you are a good woman.”

Then she turned away weeping.

That incident gave me courage. The people must be made aware that they had been fed on lies, for when they came face to face with me they knew they were false.

Another woman said: “She’s only a woman … with children.”

That provoked ribald comments; but something had happened. The woman’s tears had driven murder out of the room. They wanted to get away.

We stood behind the table for a long time and it was eight o’clock before the guards cleared the palace and we made our way over the debris of broken doors and furniture to our apartments.

I guessed that Axel would hear of this new assault and be anxious, so I sat down to write to him at once.

“I am still alive, though by a miracle. The twentieth was a terrible ordeal. But do not be anxious about me. Have faith in my courage.”

Now we were living in a damaged palace and I felt we were on the edge of disaster. As the weather grew hotter I was aware of the rising tension. The assault on the Tuileries would not be an isolated attack, I was sure of that.

I ordered Madame Campan to have a padded under-waistcoat made for the King so that if he should be attacked at any time there might be time for the guards to rescue him. It was made of fifteen folds of Italian taffeta—and comprised a waistcoat and a wide belt. I had had it tested; it resisted ordinary dagger thrust, and even shots fired at it were turned off.

I was afraid that someone would discover it and I wore it myself for three days before I had an opportunity of getting the King to try it on. I was in bed when he did so and I heard him whisper something to Madame Campan. It fitted him and he wore it, and when he had gone I asked Campan what he had said.

She was reluctant, but I said: “You had better tell me. You should understand that it is as well for me to know everything.”

She answered: “His Majesty said: ” It is only to satisfy the Queen that submit to this inconvenience. They will not assassinate me. Their schemes have changed. They will put me to death another way”.”

“I think he is right, Madame Campan,” I said. lie has told me that he believes that what is happening here is an imitation of what once happened in England. The English cut off the head of their King Charles I. I fear they will bring him to trial But I am a foreigner, my dear Madame Campan, not one of them. Perhaps they will have less scruples where I am concerned. They will very likely assassinate me.

If it were not for the children . I should not care. But the children, my dear Campan, what will become of them? “

Dear Campan was too full of sense to deny what I said. She was so practical that she immediately set about making me a corselet similar to the King’s waistcoat.

I thanked her but I would not wear it.

“If they kill me, Madame Campan, it will be fortunate for me. It will at least deliver me from this painful existence. Only the children worry me. But there are you and kind Tourzel and I do not believe that even those people would be cruel to little children. I remember how moved that woman was. It was because of the children. No, even they would not harm them. So … when they kill me, do not mourn for me.

Remember I shall go to a happier life than I suffer here. “

Madame Campan was alarmed. All during that sultry July she refused to go to bed. She would sit in my apartment dozing, ready to leap up at the first sound. I believe she saved my life on one occasion.

It was one o’clock in the morning when I started out of a doze to find Madame Campan bending over me.

“Madame !’ she whispered.

“Listen. There is someone creeping along the corridor.”

I sat up in bed startled. The corridor passed along the whole line of my apartments and was locked at each end.

Madame Campan dashed into the anteroom where the valet de chamber was sleeping. He too had heard the foot steps and was ready to rush out. In a few seconds Madame Campan and I heard the sounds of scuffling.

“Oh, Campan, Campan I’ I said, and I put my arms about the dear faithful creature.

“What should I do without friends such as you?

Insults by day and assassins by night. Where will it end? “

Tou have good servants, Madame,” she said quietly.

And it was true, for the valet de chambre at that moment came into the bedroom dragging a man with him.

“I know the wretch, Madame,” he said.

“He is a servant of the King’s toilette. He admits taking the key from His Majesty’s pocket when the King was in bed.”

He was a small man and the valet de chambre was both tall and strong, and for this I bad to be grateful otherwise it would have been the end of me that night. The miserable wretch no doubt thought to earn the praise of the mob for doing something which they were constantly screaming should be done.

I will lock him up, Madame,” said the valet de chambre.

“No,” I said.

“Let him go. Open the door for him and send him away from the palace. He came to murder me, and if he succeeded the people would be carrying him about in triumph tomorrow.”

The valet obeyed me, and when he returned I thanked him and told him that I was grieved that he should be exposed to danger on my account.

To this he replied that be feared nothing and that he had a pair of very excellent pistols which he carried always with him for no other purpose but to defend me.

Such incidents always moved me deeply, and I said to Madame Campan as we returned to my bedroom that the goodness of people such as herself and the valet would never have been appreciated by me but for the fact that these terrible times brought it home to me.

She was touched, but she was already making plans to have all the locks changed the next day, and she saw that the King’s were too.

Now the great Terror was upon us. It was as though a new race of men had filtered into the capital—small, very dark, lithe, fierce and bloodthirsty—the men of the south, the men of Marseilles.

With them they brought the song which had been composed by Rouget de Lisle, one of their officers. We were soon to hear it sung all over Paris, and it was called the “Marseillaise. Bloodthirsty words set to a rousing tune—it could not fail to win popularity. It replaced die unrilnow-favourite ” Ca ira’ and every time I heard it it made me shiver. It haunted me. I would fancy I heard it when during the night I woke from an uneasy doze, for I was scarcely sleeping during these nights.

“Allans, enfants de la Patrie, Le your de gloire est arrive.

Contre nous, de la tyrannic, Le couteau sanglant est leve, Le couteau sanglant est leve.

Entendes-vous, clans les camp agnes Mugir ces feroces soldats.

Us viennent jusque clans vos bras Egorger vos fils, vos comp agnes

Aux comes, dtoyens!

Formes vos bataillons, , Marchons, marcfwnst Qu’un sang impur Abreuve nos siltons* The gardens outside the apartments were always crowded. People looked in at the windows. At any moment one little spark would set alight the conflagration. How did we know from one hour to another what atrocities would be committed? Hawkers called their wares under my window.

“La Vie Scandaleuse de Mane Antoinette’ they shrieked. They sold figures representing me in various indecent positions with men and women.

“Why should I want to live?” I asked Madame Campan.

“Why should these precautions be taken to save a life which is not worth having?”

I wrote to Axel of the terror of our lives. I said that unless our friends issued a manifesto to the effect that Paris would be attacked if we were banned, we should very soon be murdered.

Axel, I knew, was doing everything possible. No one ever worked more indefatigably in any cause.

If only the King had had half Axel’s energy. I tried to rouse him to action. Outside our windows the guards were drawn up. If he showed them he was a leader they would respect him-I had seen how even the most crude of the revolutionaries could be overawed by a little royal dignity. I begged him to go to the guards to make some show of reviewing them.

He nodded. I was right, he was sure. He went out and it was heartbreaking to see him ambling between the lines of soldiers. He had grown so fat and unwieldy now that he , was never allowed to hunt.

I trust you,” he told them. I have every confidence in my guard.”

I heard the snigger. I saw one man break from the ranks and walk behind him imitating his ponderous walk. Dignity was what was needed.

I was a fool to nave expected Louis to show that.

I was relieved when he came in. I looked away, for I did not wish to see the humiliation on his face.

“La Fayette will save us from the fanatics,” he said heavily.

“You should not despair.”

I wonder,” I retorted bitterly, who will save us from Monsieur de La Fayette.”

The climax arrived when the Duke of Brunswick issued the Manifesto at Coblenz. Military force would be used on Paris if the least violence or outrage was committed against the King and the Queen.

It was the signal for which they had been waiting. The agitators were working harder than ever. All over Paris men were marching in groups—the sons-culottes and the ragged men of the south; they sang as they went:

“Allow enfants de la Patrie …”

They were saying that we were preparing a counterrevolution at the Tuileries.

On the tenth of August the faubourgs were on the march Hi and their objective was the Tuileries.

id A We were aware of the rising storm. All through the night of the ninth and the early morning of the tenth I had not cc taken off my clothes. I had wandered through the corridors M accompanied by Madame Campan and the Princesse de Lamballe. The King was sleeping, though fully dressed. M The tocsins had started to ring all over the city and Elisa-n beth came to join us.

w Together we watched the dawn come. That was about four o’clock, and the sky was blood-red. I said to her: “Paris must have seen something like this at the Massacre of the Saint Bartholomew.” t She took my hand and clung to it.

“We will keep together.”

I replied: “If my time should come and you survive t me …” < She nodded.

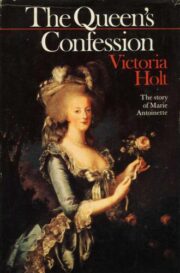

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.