“Jane, it is me,” I said. “Hannah.”

It was a sign of the depth of the queen’s grief and Jane’s despair that she did not remark on my unexpected return, nor on my new costume.

“Perhaps she’ll speak to you,” she said very quietly, alert for eavesdroppers. “Be careful what you say. Don’t mention the king, nor the baby.”

I felt my courage evaporate. “Jane, I don’t know that she would want to see me, can you ask?”

Her hands were in the small of my back pushing me forward. “And don’t mention Calais,” she said. “Nor the burnings. Nor the cardinal.”

“Why not the cardinal?” I demanded, trying to wriggle away. “D’you mean Cardinal Pole?”

“He is sick,” she said. “And disgraced. He’s recalled to Rome. If he dies or if he goes to Rome for punishment, she will be utterly alone.”

“Jane, I can’t go in there and comfort her. There is nothing I can say to comfort her. She has lost everything.”

“There is nothing anyone can say,” she said brutally. “She is as low down as a woman can be driven, and yet she has to rise up. She is still queen. She has to rise up and rule this country, or Elizabeth will push her off the throne within a week. If she does not sit on her throne, Elizabeth will push her into her grave.”

Jane opened the door for me with one hand and thrust me into the room with the other. I stumbled in and dropped to a curtsey and heard the door close softly behind me.

The room was in deep shade, still shuttered for confinement. I looked around. The queen was not seated on any of the looming chairs nor crumpled in the great bed. She was not on her knees before her prie-dieu. I could not see her anywhere.

Then I heard a little noise, a tiny sound, like a child catching her breath after a bout of sobbing. A sound so small and so thin and so poignant that it was like a child who has cried for so long that she has forgotten to cry, and despaired of the grief ever going away.

“Mary,” I whispered. “Where are you?”

As my eyes grew accustomed to the darkness I finally made her out. She was lying on the floor amid the rushes, face turned toward the skirting board, hunched like a starving woman will hunch over her empty belly. I crawled on my hands and knees across the floor toward her, sweeping aside the strewing herbs as I went, their scent billowing around me as I approached her and gently touched her shoulders.

She did not respond. I don’t think she even knew I was there. She was locked in a grief so deep and so impenetrable that I thought she would be trapped in that inner darkness for the rest of her life.

I stroked her shoulder as one might stroke a dying animal. Since words could do nothing, a gentle touch might help; but I did not know if she could even feel that. Then, I lifted her shoulders gently from the floor, put her head in my lap and took her hood from her poor weary head and wiped the tears as they poured from her closed eyelids down her tired lined face. I sat with her in silence until her deeper breathing told me that she had fallen asleep. Even in her sleep the tears still welled up from her closed eyelids and ran down her wet cheeks.

When I came out of the queen’s rooms, Lord Robert was there.

“You,” I said, without much pleasure.

“Aye, me,” he said. “And no need to look so sour. I am not to blame.”

“You’re a man,” I observed. “And men are mostly to blame for the sorrow that women suffer.”

He gave a short laugh. “I am guilty of being a man, I admit it. You can come and dine in my rooms. I had them make you some broth and some bread and some fruit. Your boy is there too. Will has him.”

I went with him, his arm around my waist.

“Is she ill?” he asked, his mouth to my ear.

“I have never seen anyone in a worse state,” I said.

“Bleeding? Sick?”

“Brokenhearted,” I said shortly.

He nodded at that and swept me into his rooms. They were not the grand Dudley rooms that he used to command at court. They were a modest set of three rooms but he had them arranged very neat with a couple of beds for his servants, and a privy chamber for himself and a fire with a pot of broth sitting beside it, and a table laid for the three of us. As we went in Danny looked up from Will’s lap and made a little crow, the greatest noise he ever made, and stretched up for me. I took him in my arms.

“Thank you,” I said to Will.

“He was a comfort to me,” he said frankly.

“You can stay, Will,” Robert said. “Hannah is going to dine with me.”

“I have no appetite,” Will said. “I have seen so much sorrow in this country that my belly is full of it. I am sick of sorrow. I wish I could have a little joy for seasoning.”

“Times will change,” Robert said encouragingly. “Changing already.”

“You’d be ready for new times, for one,” Will said, his spirit rising up. “Since in the last reign you were one of the greatest lords and in this one you were a traitor waiting for the ax. I imagine change would be very welcome to you. What d’you hope from the next, my lord? What has the next queen promised you?”

I felt a little shiver sweep over me. It was the very question that Robert Dudley’s servant had posed, the very question that everyone was asking. What might not come to Robert, if Elizabeth adored him?

“Nothing but good for the country,” Robert said easily with a pleasant smile. “Come and dine with us, Will. You’re among friends.”

“All right,” he said, seating himself at the table and drawing a bowl toward him. I hitched Danny on to the chair beside me so that he could eat from my bowl and I took a glass of wine that Lord Robert poured for me.

“Here’s to us,” Robert said, raising his glass in an ironic toast. “A heartbroken queen, an absent king, a lost baby, a queen in waiting and two fools and a reformed traitor. Here’s health.”

“Two fools and an old traitor,” Will said, raising his glass. “Three fools together.”

Summer 1558

Almost by default, I found myself back in the queen’s service. She was so anxious and suspicious of everyone around her that she would be served only by people who had been with her from the earliest days. She hardly seemed to notice that I had been away from her for more than two years, and was now a woman grown, and dressed like a woman. She liked to hear me read to her in Spanish, and she liked me to sit by her bed while she slept. The deep sadness that had invaded her with the failure of her second pregnancy meant that she had no curiosity about me. I told her that my father had died, that I had married my betrothed, and that we had a child. She was interested only that my husband and I were separated – he in France, safe, I hoped, while I was in England. I did not name the town of Calais, she was as mortified by the loss of the town, England’s glory, as she was shamed by the loss of the baby.

“How can you bear not to be with your husband?” she asked suddenly, after three long hours of silence one gray afternoon.

“I miss him,” I said, startled at her suddenly speaking to me. “But I hope to find him again. I will go to France as soon as it is possible, I will go and look for him. Or I hope he will come to me. If you would help me send a message it would ease my heart.”

She turned toward the window and looked out at the river. “I keep a fleet of ships ready for the king to come to me,” she said. “And horses and lodgings all along the road from Dover to London. They are all waiting for him. They spend their lives, they earn their livings in waiting for him. A small army of men does nothing but wait for him. I, the Queen of England, his own wife, waits for him. Why does he not come?”

There was no answer that I could give her. There was no answer that anyone could give her. When she asked the Spanish ambassador he bowed low and murmured that the king had to be with his army – she must understand the need of that – the French were still threatening his lands. It satisfied her for a day, but the next day, when she looked for him, the Spanish ambassador had gone.

“Where is he?” the queen asked. I was holding her hood, waiting for her maid to finish arranging her hair. Her beautiful chestnut hair had gone gray and thin now, when it was brushed out it looked sparse and dry. The lines on her face and the weariness in her eyes made her seem far older than her forty-two years.

“Where is who, Your Grace?” I asked.

“The Spanish ambassador, Count Feria?”

I stepped forward and handed her hood to her maid, wishing that I could think of something clever to divert her. I glanced at Jane Dormer who was close friends with the Spanish count and saw a swift look of consternation cross her face. There would be no help from her. I gritted my teeth and told her the truth. “I believe he has gone to see the princess.”

The queen turned around to look at me, her eyes shocked. “Why, Hannah? Why would he do that?”

I shook my head. “How would I know, Your Grace? Does he not go to present his compliments to the princess now and then?”

“No. He does not. For most of his time in England she has been under house arrest, a suspected traitor, and he himself urged me to execute her. Why would he go to pay his compliments now?”

None of us answered. She took the hood from the waiting woman’s hands and put it on, meeting her own honest eyes in the mirror. “The king will have ordered him to go. I know Feria, he is not a man to plot willfully. The king will have ordered him to go.”

She was silent for a moment, thinking what she should do. I kept my gaze down, I could not bear to look up and see her, facing the knowledge that her own husband was sending messages to her heir, to her rival, to his mistress.

When she turned back to us her expression was calm. “Hannah, a word with you, please,” she said, extending her hand.

I went to her side and she took my arm and leaned on me slightly as we walked from the room to her presence chamber. “I want you to go to Elizabeth,” she said quietly, as they opened the doors. There was hardly anyone outside waiting to see her. They were all at Hatfield. “Just go as if for a visit. Tell her you have recently come back from Calais and wanted to see how she did. Can you do that?”

“I would have to take my son,” I temporized.

“Take him,” she nodded. “And see if you can find out from Elizabeth herself, or from her ladies, what Count Feria wanted with her.”

“They may tell me nothing,” I said uncomfortably. “Surely, they will know I serve you.”

“You can ask,” she said. “And you are the only friend that I can trust who will gain admission to Elizabeth. You have always passed between us. She likes you.”

“Perhaps the ambassador was making nothing more than a courtesy visit.”

“Perhaps,” she said. “But it may be that the king is pressing her to marry the Prince of Savoy. She has sworn to me that she will not have him but Elizabeth has no principles, she has only appearances. If the king promised to support her claim to be my heir, she might think it worth her while to marry his cousin. I have to know.”

“When d’you want me to go?” I asked unwillingly.

“At first light tomorrow,” she said. “And don’t write to me, I am surrounded by spies. I will wait for you to tell me what she is planning when you come back to me.”

Queen Mary released my arm and went on alone into dinner. As the noblemen and the gentry rose to their feet as she walked toward the high table in the great hall I noticed how small she seemed: a diminutive woman overwhelmed by her duties in a hostile world. I watched her step up to her throne, seat herself and look around her depleted court with her tight determined smile and thought – not for the first time – that she was the most courageous woman I had ever known. A woman with the worst luck in the world.

It was a merry ride to Hatfield for Danny and me. He rode the horse astride before me until he grew too tired, and then I strapped him to my back and he slept, rocked by the jolting. I had an escort of two men to keep me safe; since the epidemic of illness of the winter, and the hardship of one bad harvest after another, the roads were continually threatened by highwaymen, bandits or just vagrants and beggars who would shout for money and threaten violence. But with the two men trotting behind us, Daniel and I were lighthearted. The weather was fine, the rain had stopped at last, and the sun was so hot by midday that we were pleased to break our fast in a field, sheltering in a wood, or sometimes by a river or stream. I let Danny paddle his feet, or sit bare-arsed in the water while it splashed around him. He was steady on his feet now, he made little rushes forward and back to me, and he continually demanded to be lifted upward to see more, to touch things, or simply to pat my face and turn my gaze this way and that.

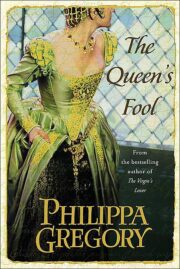

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.