I stepped back and bumped into a man walking behind me. I turned with an apology. It was John Dee.

“Dr. Dee!” My heart thudded with fright. I dropped him a curtsey.

“Hannah Green,” he said, bowing over my hand. “How are you? And how is the queen?”

I glanced around to see that no one was in earshot. “Ill,” I said. “Very hot, aching in all her bones, weeping eyes and running nose. Sad.”

He nodded. “Half the city is sick,” he said. “I don’t think we’ve had one day of clear sunshine in the whole of this summer. How is your son?”

“Well, and I thank God for it,” I said.

“Has he spoken a word yet?”

“No.”

“I have been thinking of him and of our talk about him. There is a scholar I know, who might advise you. A physician.”

“In London?” I asked.

He took out a piece of paper. “I wrote down his direction, in case I should meet you today. You can trust him with anything that you wish to tell him.”

I took the piece of paper with some trepidation. No one would ever know all of John Dee’s business, all of his friends.

“Are you here to see my lord?” I asked. “We expect him tonight from Hatfield.”

“Then I shall wait in his rooms,” he said. “I don’t like to dine in the hall without the queen at its head. I don’t like to see an empty throne for England.”

“No,” I said, warming to him despite my fear, as I always did. “I was thinking that myself.”

He put his hand on mine. “You can trust this physician,” he said. “Tell him who you are, and what your child needs, and I know he will help you.”

Next day I took Danny on my hip and I walked toward the city to find the house of the physician. He had one of the tall narrow houses by the Inns of Court, and a pleasant girl to answer the door. She said he would see me at once if I would wait a moment in his front room, and Danny and I sat among the shelves which were filled with odd lumps of rock and stone.

He came quietly into the room and saw me examining a piece of marble, a lovely piece of rock, the color of honey.

“Do you have an interest in stones, Mistress Carpenter?” he asked.

Gently, I put the piece down. “No. But I read somewhere that there are different rocks occurring all over the world, some side by side, some on top of another, and no man has ever yet explained why.”

He nodded. “Nor why some carry coal and some gold. Your friend Mr. Dee and I were considering this the other day.”

I looked at him a little more closely, and I thought I recognized one of the Chosen People. He had skin that was the same color as mine, his eyes were as dark as mine, as dark as Daniel’s. He had a strong long nose and the arched eyebrows and high cheekbones that I knew and loved.

I took a breath and I took my courage and started without hesitation. “My name was Hannah Verde. I came from Spain with my father when I was a child. Look at the color of my skin, look at my eyes. I am one of the People.” I turned my head and stroked my finger down my nose. “See? This is my child, my son, he is two, he needs your help.”

The man looked at me as if he would deny everything. “I don’t know your family,” he said cautiously. “I don’t know what you mean by the People.”

“My father was a Verde in Aragon,” I said. “An old Jewish family. We changed our name so long ago I don’t know what it should have been. My cousins are the Gaston family in Paris. My husband has taken the name of Carpenter now, but he comes from the d’Israeli family. He is in Calais.” I checked when I found that my voice shook slightly at his name. “He was in Calais when the town was taken. I believe he is a prisoner now. I have no recent news of him. This is his son. He has not spoken since we left Calais, he is afraid, I think. But he is Daniel d’Israeli’s son, and he needs his birthright.”

“I understand you,” he said gently. “Is there any proof you can give me of your race and your sincerity?”

I whispered very low. “When my father died, we turned his face to the wall and we said: “Magnified and sanctified be the name of God throughout the world which He has created according to His will. May He establish His kingdom during the days of your life and during the life of all of the house of Israel, speedily, yea soon; and say ye, Amen.”

The man closed his eyes. “Amen.” And then opened them again. “What do you want with me, Hannah d’Israeli?”

“My son will not speak,” I said.

“He is mute?”

“He saw his wet nurse die in Calais. He has not spoken since that day.”

He nodded and took Daniel on to his knee. With great care he touched his face, his ears, his eyes. I thought of my husband learning his skill to care for the children of others, and I wondered if he would ever again see his own son, and if I could teach this child to say his father’s name.

“I can see no physical reason that he should not speak,” he said.

I nodded. “He can laugh, and he can make sounds. But he does not say words.”

“You want him circumcised?” he asked very quietly. “It is to mark him for life. He will be known as a Jew then. He will know himself as a Jew.”

“I keep my faith in my heart now,” I said, my voice little more than a whisper. “When I was a young woman I thought of nothing, I knew nothing. I just missed my mother. Now that I am older and I have a child of my own I know that there is more than the bond of a mother and her child. There is the People and our faith. Our little family lives within our kin. And that goes on. Whether his father is alive or dead, whether I am alive or dead, the People go on. Even though I have lost my father and my mother and now my husband, I acknowledge the People, I know there is a God, I know his name is Elohim. I still know there is a faith. And Daniel is part of it. I cannot deny it for him. I should not.”

He nodded. “Give him to me for a moment.”

He took Daniel into an inner room. I saw the dark eyes of my son look a little apprehensively over the strange man’s shoulder, and I tried to smile at him reassuringly as he was carried away. I went to the window and held on to the window latch. I clutched it so tightly that it marked my palms and I was not aware of it until my fingers had cramped tight. I heard a little cry from the inner room and I knew it was done, and Daniel was his father’s son in every way.

The rabbi brought my son out to me and handed him over. “I think he will speak,” was all he said.

“Thank you,” I replied.

He walked to the front door with me. There was no need for him to caution me, nor for me to promise him of my discretion. We both knew that on the other side of the door was a country where we were despised and hated for our race and for our faith, even though our race was the most lost and dispersed people in the world, and our faith was almost forgotten: nothing left but a few half-remembered prayers and some tenacious rituals.

“Shalom,” he said gently. “Go in peace.”

“Shalom,” I replied.

There was no joy at the court in Whitehall, and the city, which had once marched out for Mary, now hated her. The pall of smoke from the burnings at Smithfield poisoned the air for half a mile in every direction; in truth it poisoned the air for all of England.

She did not relent. She knew with absolute certainty that those men and women who would not accept the holy sacraments of the church were doomed to burn in hell. Torture on earth was nothing compared with the pains they would suffer hereafter. And so anything that might persuade their families, their friends, the mutinous crowds who gathered at Smithfield and jeered the executioners and cursed the priests, was worth doing. There were souls to be saved despite themselves and Mary would be a good mother to her people. She would save them despite themselves. She would not listen to those who begged her to forgive rather than punish. She would not even listen to Bishop Bonner who said that he feared for the safety of the city and wanted to burn the heretics early in the morning before many people were about. She said that whatever the risk to her and to her rule, God’s will must be done and be seen to be done. They must burn and they must be seen to burn. She said that pain was the lot of man and woman and was there any man who would dare to come to her, and ask her to let her people avoid the pain of sin?

Autumn 1558

In September we moved to Hampton Court in the hopes that the fresh air would clear the queen’s breathing, which was hoarse and sore. The doctors offered her a mixture of oils and drinks but nothing seemed to do her any good. She was reluctant to see them, and often refused to take her medicine. I thought she was remembering how her little brother had been all but poisoned by the physicians who tried one thing and then another, and then another; but then I realized that she could not be troubled with physic, she no longer cared for anything, not even her health.

I rode to Hampton Court with Danny in a pillion saddle behind me for the first time. He was old enough and strong enough to ride astride and to hold tightly on to my waist for the short journey. He was still mute, but the wound had healed up, and he was as peaceful and as smiling as he had always been. I could tell by the tight grip on my waist that he was excited at the journey and at riding properly for the first time. The horse was gentle and steady and we ambled along beside the queen’s litter down the damp dirty lanes between the fields where they were trying to harvest the wet rye crop.

Danny looked around him, never missing a moment of this, his first proper ride. He waved at the people in the field, he waved at the villagers who stood at their doorways to watch as we went by. I thought it spoke volumes for the state of the country that a woman would not wave in reply to a little boy, since he was riding in the queen’s train. The country, like the town, had turned against Mary and would not forgive her.

She rode with the curtains of the litter drawn, in rocking darkness, and when we got to Hampton Court she went straight to her rooms and had the shutters closed so that she was plunged into dusk.

Danny and I rode into the stable yard, and a groom lifted me down from the saddle. I turned and reached up for Danny. For a moment I thought he would cling and insist on staying on horseback.

“Do you want to pat the horse?” I tempted him.

His face lit up at once and he reached out his little arms for me and came tumbling down. I held him to the horse’s neck and let him pat the warm sweet-smelling skin. The horse, a handsome big-boned bay, turned its head to look at him. Danny, very little, and horse, very big, stared quite transfixed by each other, and then Danny gave a deep sigh of pleasure and said: “Good.”

It was so natural and easy that for a moment I did not realize he had spoken; and when I did realize, I hardly dared to take a breath in case I prevented him speaking again.

“He was a good horse, wasn’t he?” I said with affected nonchalance. “Shall we ride him again tomorrow?”

Danny looked from the horse to me. “Yes,” he said decidedly.

I held him close to me and kissed his silky head. “We’ll do that then,” I said gently. “And we’ll let him go to bed now.”

My legs were weak beneath me as we walked from the stable yard, Danny at my side, his little hand reaching up to hold mine. I could feel myself smiling, though tears were running down my cheeks. Danny would speak, Danny would grow up as a normal child. I had saved him from death in Calais, and I had brought him to life in England. I had justified the trust of his mother, and perhaps one day I would be able to tell his father that I had kept his son safe for love of him, and for love of the child. It seemed wonderful to me that his first word should be: “good.” Perhaps it was a foreseeing. Perhaps life would be good for my son Danny.

For a little while the queen seemed better, away from the city. She walked by the river with me in the mornings or in the evenings; she could not tolerate the brightness of midday. But Hampton Court was filled with ghosts. It was on these paths and in these gardens where she had walked with Philip when they were newly married and Cardinal Pole newly come from Rome and the whole of Christendom stretched before them. It was here that she had whispered to him that she was with child, and gone into her first confinement, certain of her happiness, confident of having a son. And it was here that she came out from her confinement, childless and ill, and saw Elizabeth growing in beauty and exulting in her triumph, another step closer to the throne.

“I feel no better here at all,” she said to me one day as Jane Dormer and I came in to say goodnight. She had gone to bed early again, almost doubled-up with pain from the ache in her belly and feverishly hot. “We will go to St. James’s Palace next week. We will spend Christmas there. The king likes St. James’s.”

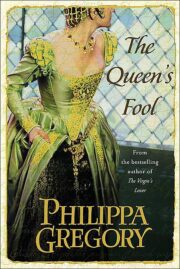

"The Queen’s Fool" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Fool". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Fool" друзьям в соцсетях.