‘Your Majesty has the kindest heart in the world,’ said Lord Melbourne. ‘And kindness is a much higher quality than moral rectitude.’

‘Oh, Lord M, do you really think so?’

‘I am sure of it. And I am sure the recording angel will agree with me.’

‘Lord M, you say the most shocking things.’

‘If they bring a smile to Your Majesty’s lips I am satisfied.’

It was such good fun to be with Lord Melbourne, though the Opposition was giving them a great deal of trouble over the China policy, he said, and then there was the bill for the union of the two Canadas. He could see that trouble was looming in Afghanistan and he was not sure what would come out of that.

‘That dreadful Sir Robert Peel, I suppose.’

Lord Melbourne raised his beautifully arched eyebrows, which she used to admire so much, and still did, of course. Lord Melbourne was a very handsome man but no one had quite the same breathtaking beauty as Albert.

‘Oh, he’s a good fellow, you know.’

‘He’s a monster.’

‘All men, in a manner of speaking, are monsters who don’t agree with the Queen and her Prime Minister – but apart from that they can be damned good fellows … Your Majesty will forgive my language.’

She bowed her head with a smile; but even then she thought: Albert would be shocked if he had heard the Prime Minister say damned in the presence of the Queen.

Yet how she had always loved Lord M’s racy conversation! And if Albert ever joined them in the blue closet there would have to be a stop to it.

Lord Melbourne then went on to tell her that Lord William Russell’s Swiss valet, Benjamin Courvoisier, had confessed to murdering his master. It was an intriguing story because the valet had come into his master’s bedroom in Norfolk Place, Park Lane, stark naked so that there would be no blood on his clothes. He had borrowed from the Duke of Bedford’s valet a copy of Jack Shepherd by the author Harrison Ainsworth and this had apparently inspired him. His motive was robbery as he wanted to get back to Switzerland.

Lord William always slept with a light by his bedside and someone from the opposite window saw the naked figure in the bedroom from across the road. He didn’t come forward to give evidence because he was a well-known General and was spending the night there with a lady in society.

‘How very shocking!’ said Victoria.

‘Well, that is the way of the world,’ replied Lord Melbourne. ‘Courvoisier has confessed. I doubt you will hear the story of the General and his lady friend, but it is being well circulated and the considered opinion seems to be that there is some substance in it.’

How very, very shocking! she thought. But she was glad to hear of it. Lord Melbourne did bring her all the little titbits of gossip which were so enlivening.

But she could not talk to Albert of them. He certainly would not approve.

They were going to Claremont. It would be good for her, said Albert, to get out into the fresh air more; he was going to be very strict with her, he told her playfully. They were going to rise early and retire to bed early; they would walk in the beautiful gardens; he would teach her something about the plants and birds – of which she was abysmally ignorant; they would sketch together; he would read aloud to her and they would discuss the book afterwards; they would sing duets together and play the piano. It seemed a delightful existence.

‘Dear Albert,’ she said, ‘how careful you are of me.’

‘But of course, my love, it is my duty.’

‘Oh, Albert, is that all?’

‘And my pleasure,’ he added gently.

So to Claremont, but there were too many memories and even Albert could not disperse them.

She told him about dear Louie whom she had met there in her childhood. ‘She had her own special curtsy and she was very much on her dignity until we were in her room alone … just the two of us, and then I was no longer the Princess Victoria, but her visitor. She used to make tea and we would sit drinking it while she talked of the old days, mostly of Princess Charlotte.’

‘Yes. Uncle Leopold has told me so much about Claremont. It is an enchanting place.’

So more walking, playing music, retiring early and rising early; it was all as Albert wished, and Victoria was not sorry for the change. But the place seemed haunted by Charlotte. Here Charlotte had given birth to the still-born child who should have been ruler of England; and Charlotte herself who was first to have been Queen, died also.

Louie was also dead. Sometimes when she went into her old room Victoria would imagine her coming out of the shadows to give that special curtsy to Victoria, the girl who had taken the place of Charlotte in her heart.

This had been Uncle Leopold’s home and he wrote to her telling her how pleased he was that she was staying for a while at Claremont where she must, whether she wished it or not, be reminded of him. There, he reminded her, she had spent many happy days in her childhood. It had been a kind of refuge for her. He knew that she had been a little plagued at Kensington and how she had benefited from that respite she had enjoyed at Claremont.

It was true, of course. How she had adored meeting Uncle Leopold there! He had been the most important person in her life then, until she had become on such friendly terms with Lord Melbourne who, she now saw, had taken her uncle’s place. And now there was Albert, dear beautiful Albert, whom she loved as she could never love anyone else in the world. There was a warning in Uncle Leopold’s letter. He had heard that she was being just a little dictatorial with Albert. Oh, people did not understand how difficult it was to be the Queen and a wife as well.

She may have been given an impression, wrote Uncle Leopold, that Charlotte had been imperious and rude. This was not so. She had been quick and sometimes violent in her temper, but she had been open to conviction and always ready to admit she was in the wrong when this was proved to be the case. Generous people, when they saw that they were wrong, and that reasons and arguments submitted to them were true, frankly admitted this to be so. He knew that she had been told that Charlotte had ordered everything in the house and liked to show that she was mistress. That was untrue. Quite the contrary. She had always tried to make her husband appear to his best advantage and to display respect and obedience to him. In fact sometimes she exaggerated this to show that she considered the husband to be the lord and master.

He must tell her an amusing little incident. Charlotte was a little jealous. There had been a certain Lady Maryborough whom she fancied he had a liking for. This was absolutely untrue. The lady was some twelve or perhaps fifteen years older than he was but Charlotte thought he had paid too much attention to her. Poor Charlotte! At such times she was a little uncontrolled, which if she had become Queen would never have done. Her manners had been a little brusque, he confessed, and this at times often pained the Regent – ‘your Uncle George’. This had its roots in shyness for she was very unsure of herself – probably due to her extraordinary upbringing – and was constantly trying to exert herself.

I had – I may say so without seeming to boast – the manners of the best society in Europe, having early mixed in it and been rather what is called in French

de la fleur des pots

. A good judge, I therefore was, but Charlotte found it rather hard to be so scrutinised and grumbled occasionally how I could so often find fault with her.

She understood the meaning between the lines of Uncle Leopold’s long letter. How very similar her position was to that of Charlotte! Charlotte, of course, was never the Queen, but everyone thought she would be. The only daughter of King George IV – and married to Uncle Leopold. Uncle Leopold was a little like dear Albert. He was extremely handsome, clever and liked to take a part in affairs. Of course he was Albert’s uncle as well as hers.

She thought a great deal about Charlotte. She had heard so much of the happy days her cousin had spent here, first under the adoring eyes of dear Louie and later under the tenderly corrective ones of Uncle Leopold.

It was so easy to substitute herself for Charlotte. They were of an age; one had a crown and for the other it must have seemed almost a certainty that the crown would have been hers. During the months when she awaited her baby she must have walked in these gardens of Claremont. Her husband Leopold was here, just as Victoria’s husband Albert was. The husbands would even have looked alike for there was a strong family resemblance.

She could almost identify herself with Charlotte. They were of an age, both just married, both in love, both pregnant and both aware of the burden of the crown.

She went to the rooms which had been Charlotte’s. There the young girl had had her confinement. Her child had been born dead … and she poor girl had followed after.

It was all so similar. How often during her life had Charlotte wondered whether there would be a brother to supplant her and block her way to the throne? How often had Victoria wondered whether Uncle William and Aunt Adelaide would have a child? Victoria could see those lovers Charlotte and Leopold and it was as though they were in truth Victoria and Albert.

She had made a habit of going to the room in which Charlotte had died, and thinking of what her cousin must have suffered. It was like poor Lady John Russell.

‘I am afraid,’ she whispered, ‘that it will happen to me.’

One day when she went to the room and stood there looking at the bed and imagining that last scene which Uncle Leopold had described in detail – how he had knelt by the bed and wept for his beloved Charlotte and how her last thoughts had been for him – she was filled with terror because it seemed like a recurring pattern. The child within her would be as that other child; she would be as the poor princess who had died in her ordeal, and dear Albert would be collapsing by the bed in his grief as Uncle Leopold had. Yes, a tragic pattern.

The door handle turned silently. She gave a gasp. She thought it was the ghost of Charlotte come back from the grave to warn her that her end was near.

It was Albert.

‘Victoria, what are you doing in this room?’ he asked.

‘I come here often.’

‘I know, and I ask why.’

‘In this room my cousin Charlotte died having her baby. Had she lived she would have been Queen of England.’

‘You should not come here, Victoria.’

‘I feel impelled to do so.’

Then Albert spoke with the authority of a husband. ‘We are leaving Claremont tomorrow,’ he said.

She just lay against him, comforted. For once he was to have his way.

They were back in London and, although Albert disliked the capital and was never in it without planning his next visit to the country where he might breathe the fresh air which made him feel so much more alive and healthy, he was excited and certainly apprehensive because he had been asked to preside at a meeting. This was to promote the abolition of the slave trade and he was to make his first speech in England.

He was very nervous, he told Victoria. ‘I have to convince the people of my serious interest in affairs,’ he told her. ‘I do not wish them to think me frivolous.’

‘They could never think you that, Albert,’ she told him fondly.

She had been very happy since he had drawn her away from her brooding at Claremont. ‘How very silly I was,’ she had said. ‘And you, dearest Albert, showed me so in the nicest possible way.’

Yes, his attempt at playing the masterful husband had succeeded; and now, due to the joint efforts of Stockmar and Lord Melbourne, he was allowed to develop his interest in what was going on and this public appearance was the result.

‘It is very difficult to speak in English,’ said Albert.

‘You will manage admirably,’ the Queen told him. ‘Let me hear your speech.’

It was short and, she said, excellent. She corrected his pronunciation and suggested he rehearse it again. She was delighted because she quickly knew it off by heart and could listen and correct without having to have the written version before her.

‘It is well to be a little nervous,’ the Queen assured him. ‘I do believe that all the best speakers are. Lord Melbourne says that when he is completely at ease he never really speaks well.’

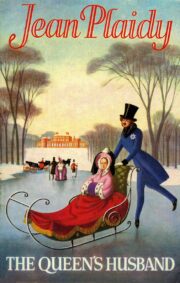

"The Queen’s Husband" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Husband". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Husband" друзьям в соцсетях.