‘Albert is inclined to admire Sir Robert Peel. I never want to talk about that man with Albert because it makes my temper rise.’

‘You will overcome that dislike. It is not good for a queen to bear personal animus towards a great statesman.’

‘I shall never like Sir Robert Peel,’ said the Queen shortly.

Aunt Augusta had become very ill and the family knew that she was dying. The Queen, who had an enduring affection for her family, was deeply affected. She had always been a pet of the aunts and was in constant touch with them. They looked forward to her visits and she had been determined from the time of her accession that they should know that the Queen never forgot the duties and affections of the niece.

There was poor Aunt Sophia, about whom scandal still lingered, although it was long ago when she had borne her illegitimate son. Sophia’s eyesight was fading fast, for she suffered from cataracts, and this was a great sadness for she had loved tatting and embroidering and many a bag fashioned by Sophia’s hands had come into Victoria’s possession. Now one of her great pleasures were the visits from her dear little niece who had become the most important lady in the land. There was dear old Aunt Gloucester whom Victoria had always thought of as a sort of grandmother. And poor Augusta who now needed special attention.

Victoria was always ‘her darling’ and she referred to her as such.

‘Is that my darling come to see me?’ she would say; or, ‘I hear my darling was such a success at this or that function.’

It was very touching, said Victoria.

She would sing to Aunt Augusta when she visited her – very often some of Aunt Augusta’s own compositions, for in her youth this aunt had been quite talented. Had she not been a princess she might have been a musician or an artist. ‘But I was not encouraged,’ she once told Victoria. ‘My mother, your Grandmama, Queen Charlotte, believed I did my duty by walking the dog and making sure that her snuff box was filled. She was a great snuff taker. And your grandfather, King George III, thought that there was only one musician worthy of the name and that was Handel.’

Poor dear Aunt Augusta who had never really done what she wanted to!

Victoria was always interested to hear stories of her aunts’ early life with her grandparents. It was pleasant to feel that one belonged to a family, and because it happened to be the royal family that did not mean that it was in all fundamental details different from any other. One of Lord Melbourne’s great charms was that he had lived such a long time and could enchant her with stories of the past – many concerning the eccentric members of her family.

It was so sad, therefore, to contemplate the breaking with yet another of these links with the past.

Aunt Adelaide, the Dowager Queen, nursed Aunt Augusta. Adelaide could always be relied on at such times. There was something very unroyal about Adelaide, and Victoria had loved her from the time when she had presented her with the Big Doll and tried so hard to bring her to the parties of which Victoria’s Mama did not approve.

Albert said: ‘You must not wear yourself out, my love, with these visits to your aunt’s sick room.’

‘But she loves to see me, Albert. I could not fail her.’

Albert always understood the need to do one’s duty.

It was rather a relief when on the 22nd of September Aunt Augusta died. All the family were gathered together in the death chamber, but it was the Dowager Queen Adelaide who had nursed her through her illness, to whose hand she clung at the end.

Albert took his wife back to the palace where he masterfully insisted that she rest. As soon as the funeral was over he was going to take her down to Claremont to get her right away.

Lehzen said that surely Claremont was not a good choice; but the Queen, since Albert had suggested it, decided that she would go there.

Once in the old mansion she realised that it had been rather a mistake to go there. Lehzen was right. It would have been much better to have gone to Windsor.

She found herself hurrying past the room in which Charlotte had died and she began to brood on her own ordeal which was very close now.

Lehzen at last insisted on their return. A very unpleasant rumour was being circulated that the Queen had had a premonition that like her cousin Charlotte she was going to die in attempting to give the nation its heir. It was for this reason that she had gone to Claremont. One story was that she was having the lying-in chamber decorated in exactly the same way it had been done at the time of Charlotte’s death.

‘My precious love,’ said Lehzen, ‘it is quite morbid to be here. You should be in London. That will be much better for you. It was a foolish idea to come here.’

Victoria was silent, knowing whose idea it was. But she was glad to return to London.

The government was involved in such political trouble, and so great was Victoria’s fear that it would fall, that she forgot her personal discomfort.

The oriental situation was very grave. Afghanistan was in a state of uproar; fighting had broken out in China and Lord John Russell and Lord Palmerston were disagreeing with each other within the party.

‘A split in one’s own ranks is more dangerous than any attack from the Opposition,’ said Lord Melbourne. ‘It could bring the government down.’

In concern the Queen wrote to her Prime Minister:

For God’s sake do not bring on a crisis; the Queen really could not go through that

now

, and it might make her

seriously ill

if she were to be kept in a state of agitation and excitement if a crisis were to come on; she has already had so much lately in the distressing illness of her poor aunt to harass her …

Albert, who had had a desk brought into her study and placed beside hers, had been reading the documents which had been arriving at the palace and she found how comforting it was to discuss these affairs with him. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘I can be of real use to you.’

‘Dear Albert,’ she murmured, ‘that will be a great comfort.’ It was amazing how dependent pregnancy made her feel and what pleasure she took in seeing that handsome face so near her own. She could tell him of her fears of the government’s collapse and he could soothe her by replying that if the government did fall it was her duty to be just towards any new government which the country might desire.

‘I could never accept that dreadful Peel man,’ she said.

‘But my dear love is a queen and would never forget that, and, however difficult you found it, remember I should be there to help you.’

‘Yes, Albert,’ she said meekly.

It was very comforting to talk to Albert about that wicked man Mehemet Ali who was causing all the trouble. But the French were being their usual difficult selves and once again Uncle Leopold was deploring the English attitude towards that country.

England with Russia, Prussia and Austria had delivered an ultimatum to Mehemet Ali insisting that he leave North Syria or be ejected by force. France, although deeply involved, and committed to help, stood aloof, which made the situation a very dangerous one, and conflict in Europe must of course give greater cause for alarm than what was happening in the East.

Uncle Leopold wrote that while he did not think France had acted wisely he could not help adding that England had behaved harshly and insultingly towards France. Victoria was able to reply that no one but France was to blame for her unfortunate position, for that country was committed to join the allies and had refused.

Still, she wrote, though France is in the wrong, and

quite

in the wrong, still I am most anxious, as I am sure my Government also are, that France should be pacified and should again take her place among the five great powers …

Albert, who sends his love, is much occupied with Eastern affairs and is quite of my opinion …

It was comforting to be able to write that. Uncle Leopold had always been anxious that Albert should have the opportunity to advise her. Well now he had, and he was on her side. Not that Albert’s opinion could weigh against that of Lords Melbourne and Palmerston; but there was no doubt that Albert could offer his opinions, which Lord Melbourne said were balanced and reasonable.

As the weeks passed there were continually dispatches from the Prime Minister and the Foreign Secretary; and they and other Ministers were calling frequently at the palace. The oriental controversy aggravated by the intransigent attitude of the French was the matter of the moment.

‘When the baby is born it ought to be called Turko-Egypto,’ said the Queen with grim jocularity.

It was November and, although the baby was not expected before the beginning of December, three doctors – Sir James Clark, Dr Locock and Dr Blagden – together with the nurse, Mrs Lilly, were all installed in the palace. As Dr Stockmar was also at Court Albert had asked him to be ready to assist if his services should be needed.

Three weeks before the expected time the Queen’s pains began. In spite of previous apprehension she was quite calm. Albert remained in the room with the doctors and Mrs Lilly and Victoria’s greatest concern was that the pain would be so great that she might be unable to restrain her cries. That, she feared, would be most undignified, for waiting in the next room were the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston and other important Ministers and gentlemen of rank. Close by, but in a separate room, were members of her household. It was the public nature of the proceedings which was so undignified, but this did make her determined to exert the utmost control.

Albert was a comfort. She sensed his anxiety. Dear Albert, everything must go well for his sake.

How wonderful it would be if she could produce a dear little boy exactly like his father – and what was more important was that he should be as good.

After twelve hours of labour the baby was born. The Queen lay back exhausted but triumphant. Albert came to the bed to hold her hand.

‘The child?’ she asked.

‘Is perfect,’ answered Albert.

‘A boy?’

The doctor answered. ‘It is a Princess, Your Majesty.’

There was a moment of disappointment. Albert pressed her hand warmly.

‘Never mind,’ she said. ‘The next one will be a Prince.’

‘My dearest,’ said Albert, ‘we should not be sad because we have a little girl. It is a poor compliment to you. Why, this child could become a queen as good as her mother.’

‘Dear Albert. Then you are not displeased?’

‘If you get well quickly then I am content,’ said Albert.

Mrs Lilly had washed the little Princess and placed her naked on a velvet cushion. Then she walked with her into the room where the members of the government had been waiting.

‘Here is Her Highness the Princess Royal,’ she announced.

The old Duke of Wellington came forward to peer at the child.

‘Oh,’ he said in a tone of mild contempt, ‘a girl.’

Mrs Lilly glared at him. ‘A Princess, Your Grace,’ she said sharply, for she would have the old gentleman remember that although the precious child was a girl she was as royal as any boy could be.

Chapter IX

IN-I-GO JONES

The baby was to be named Victoria after her mother, and the names Adelaide Mary Louise were added. The Dowager Queen was delighted that the child was called after her; she was so happy, she told the Queen, that she had experienced the blessing of motherhood. Poor Adelaide, how she had always longed for a child of her own; but being of the sweetest of temperaments she would not grudge anyone else the happiness which she had missed.

‘Aunt Adelaide will be ready to spoil the child,’ said Victoria to Albert.

‘That must not be allowed,’ replied Albert. He was determined to be a good father and that did not include spoiling his offspring.

It was rather awkward that she had the same name as her mother, but Albert had wished it – ‘Such a delightful compliment,’ said the Queen – and she herself had thought it appropriate, so the child was Victoria.

‘She is like a little kitten,’ said the Queen and from then on the child was called Pussy and sometimes, to vary it, Pussette.

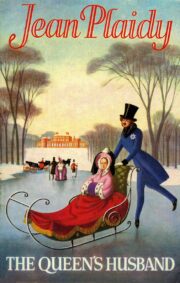

"The Queen’s Husband" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Husband". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Husband" друзьям в соцсетях.