Victoria discovered that although she had enjoyed racing up and down the corridors of Buckingham Palace with the Conyngham children or those of the John Russells, she was not so fond of little babies. She was delighted, of course, to be a mother and so quickly to have produced a child (it was only nine months since her marriage) but that did not mean that she wanted to spend all her time in the nursery. She was no Aunt Adelaide.

A wet nurse was procured with other nurses and the Baroness Lehzen decided that the nursery was a place in which she should reign supreme. Victoria was delighted that dear Daisy should superintend the baby’s domain and returned to her everyday life.

The oriental situation had taken a turn for the better. Mehemet Ali had given up his claims to Syria on the intervention of the allied fleet and stated that he would relinquish the Ottoman fleet if the allies would give him possession of the Pashalik of Egypt.

‘A very happy end to the year,’ commented Victoria to Albert. ‘The crisis over and a baby in the nursery.’

Uncle Leopold was delighted that she had proved herself able to bear healthy children. It was always a fear in the royal family that this might not be the case. George III had had far too many but his sons, George and William, had not followed his example; and now at the age of twenty-one, after less than a year of marriage, the Queen had produced a child. There would of course be more, as Leopold implied in his letter.

I flatter myself, he wrote, that you will be a delighted and delightful

Maman au milieu d’une belle et nombreuse famille

.

Indeed! thought Victoria when she read it. The idea of going through all that again to produce a large family did not please her. Of one thing she had made very sure. If she had another child – and she did not intend to for some little time – she would arrange that the child was born before any of the dignitaries were summoned to the palace.

‘For I will not have a public birth again,’ she confided to Lehzen.

‘I should think not,’ said the Baroness. ‘I had thought that the Prince might have realised your wish for privacy when Pussy was born.’

‘It’s the old tradition, Lehzen. Remember the baby in the warming-pan rumour? They think someone might smuggle in a spurious child.’

‘What nonsense! But I shall insist that my dearest love does not suffer that again. And I hope that the next occasion will be postponed for at least two years. I know you look blooming, but you do need time to recover from having the child.’

Victoria wrote a little tersely to Uncle Leopold. He did like to interfere just a little too much. He had tried to tell Lord Melbourne and Lord Palmerston how to conduct the Turko-Egyptian matter and he was constantly criticising Lord Palmerston.

I think, dearest Uncle, you cannot wish me to be the ‘

Maman d’une nombreuse famille

’ for I think you will see with me the great inconvenience a

large

family would be to us all, and particularly to the country, independent of the hardship and inconvenience to myself; men never think, at least seldom think, what a hard task it is for us women to go through this

very often

.

No, she would certainly wait a few years. Lehzen was quite right about this.

Poor Dash was showing his age. He no longer leaped up barking and wagging his tail when a walk was mentioned. Instead he was rather inclined to hide himself so that he didn’t have to go out. He slept in a basket by the royal bed; he used to be very fierce and at the least sound would waken everyone near by.

But on that early December morning Dash slept on while the door handle of the Queen’s dressing-room was slowly turned and silently opened.

Mrs Lilly awoke and looked about her.

‘Is anyone there?’ she whispered.

There was no answer so she sat up, listening.

Another sound. There was no doubt about it. Someone was prowling about the Queen’s dressing-room.

She went to the door, listening. An unmistakable sound. Yes, someone was in there. She locked the door and called one of the pages.

He came rubbing the sleep out of his eyes.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

‘When I unlock this door,’ said Mrs Lilly, ‘you will go in and bring out whoever is in there.’

The man stared at her. ‘Someone …’

‘Do as I say.’

‘Me! Why? Suppose he’s got a gun?’

A figure with a candle had appeared in the corridor. It was the Baroness Lehzen.

‘What is happening here?’ she demanded. ‘You will awaken the Queen.’

‘Oh, Baroness,’ said Mrs Lilly, ‘I’m sure I heard someone in the Queen’s dressing-room.’

‘Mein Gott!’ cried the Baroness. ‘And you stand here. The Queen may be murdered.’

She pushed them aside, unlocked the door and strode into the dressing-room like an avenging angel. Her precious darling in danger and these fools standing about doing nothing. She was thinking of the madman who had taken a shot at Victoria on Constitution Hill. So were the others, but this had the opposite effect on the devoted Lehzen.

She looked round the room. She could see no one. The only place where anyone could be hidden was under the sofa. Thrusting the candlestick into the hands of Mrs Lilly she pushed the sofa to one side.

There was a gasp. Cowering under the sofa was a small boy, his clothes ragged, his face dirty, his eyes wide with astonishment.

Who was the boy? He had been some days in the palace, he told them. He had hidden under the sofa on which the Queen and Prince Albert had sat and had lain there listening to them talking together; he had been to the throne room and sat on the throne; he had been in the nursery and heard the new baby Princess cry.

He loved Buckingham Palace. He confessed to having been there before. Last time had been in 1838 when he had spent a week there and he could not resist paying another visit.

People remembered the excitement of two years earlier. Of course he was the Boy Jones. Someone had waggishly christened him In-I-go Jones.

It was considered to be an amusing incident. The boy had done little harm. He had merely been curious.

The Queen laughed when she heard of it, but Albert took a different view.

‘My dear love,’ he said, ‘it alarms me that people could so easily get into the palace.’

‘It was only a boy,’ said Victoria.

‘Only a boy this time. But if a boy can get in so easily how much more easily could someone enter who might wish to do harm.’

‘He came before,’ said Victoria; ‘fancy that.’

Albert was thoughtful.

Albert had been making an investigation of the manner in which the household was managed. He was determined to find out how it was possible for a boy to get into the palace and spend several days there unobserved.

In one of the kitchens he found a broken pane of glass.

‘How long has that been broken?’ he asked.

The kitchen hand to whom he addressed the question scratched his head. ‘Well, Your Highness, it were done last Saturday week. I know for sure.’

Another kitchen hand came up and said the window had been like that for a month.

‘Whose duty would it be to see that it was repaired?’ the Prince wanted to know.

They didn’t know, but they would call the chief cook.

‘It’s like this, Your Highness,’ said the chief cook, ‘I’d write and sign a request to have the glass put back, but the Clerk of the Kitchen would have to sign it too.’

‘And did you?’

‘I did, Your Highness, two months ago.’

‘Send me the Clerk of the Kitchen,’ said Albert.

The Clerk of the Kitchen remembered signing the request but then it had to go to the Master of the Household.

The Master of the Household had signed so many requests that he did not remember the pane of glass in particular, but his duty was to take it to the Lord Chamberlain’s office and there it would await attention.

‘And what happens there?’ asked the Prince.

‘The Lord Chamberlain would sign and then it would go to the Clerk of the Works, Your Highness.’

‘Mein Gott!’ cried the Prince breaking into German, as he did when seriously disturbed. ‘All this for a pane of glass! And meanwhile people can break into the palace and, if they have a mind to, murder the Queen.’

His orderly Teutonic soul was outraged. He was certain that this was not the only anomaly. The servants’ domain was a little kingdom on its own. He could see that there was no discipline whatsoever. Servants absented themselves when they thought fit, or brought in their friends and entertained them at the Queen’s expense.

He was horrified.

His questions quickly aroused suspicions which were deeply resented. The Baroness Lehzen, who was in charge of the keys, although she had no special title, never bothered them. She had other matters with which to concern herself than what went on in the kitchens. As long as she had her caraway seeds served with every meal, and when there was a state banquet or a dinner party food appeared on the table, that was all that mattered.

The servants grumbled together that they wanted no meddling German coming to their quarters to spy on them.

The Prince’s investigations were reported to the Baroness, so she was ready for him.

He came to her room one day and told her about the pane of glass which had been missing for months because the inefficiency of the system had made it impossible for the request to reach the right person.

‘I did not know Your Highness would concern himself with such a little thing.’

‘It is of great concern. That boy got into the palace. How?’

‘Not through that broken window surely?’

‘He was in the palace because there is a lack of security.’

Lehzen said: ‘As soon as I heard a commotion near the Queen I was out of bed. I have looked after her for years. The slightest sound … and I am there.’

‘That is not the point,’ said the Prince patiently.

The Baroness broke into German. He followed. It was easier for them both. The Baroness was trying hard to control her anger; she had to remember that he was the Queen’s husband. He found it easier to remain calm. He must not quarrel with her. She would distort what he said and carry tales to the Queen.

But in those moments there was one fact which was clear to them.

There was not room for them both in the palace.

Albert said: ‘My love, I want to talk to you about palace security.’

‘Oh, Albert, are you worrying about the Boy Jones?’

‘It has started me thinking, and I have been looking into these matters. Really, there are some strange things going on in your household.’

‘What do you mean, Albert?’

‘Well, for one thing it takes months to get a pane of glass repaired.’

‘Does it?’

‘All because of stupid mismanagement. I want to go into all the details of the household management. I think we could dismiss several of the servants who are of no use at all.’

‘Dismiss them! Oh, but Albert, where would they go?’

‘To some households which could find work for them. There is not enough here for so many.’

‘It has been going on for years, Albert.’

‘All the more reason why it should go on no longer. I want the keys of the household.’

‘Lehzen has them.’

‘Well, they must be taken away from her.’

‘Must, Albert?’

‘Yes, since she mismanages everything in this way.’

‘Albert! I couldn’t possibly take the keys away from Lehzen. She would be so hurt.’

‘Then hurt she must be. You should tell her that I am not satisfied with the way in which she allows the household to be run.’

‘But I am satisfied, Albert.’

‘How can you be?’

‘Because it has been running for years and I never heard any complaint before. Besides, it is not for you to run the household.’

‘I disagree.’

She was tired and the baby was always crying and not such fun as she had thought a baby would be. She was worried about Dash, who wouldn’t eat anything and looked at her with sad mournful eyes. And Albert plagued her about the household!

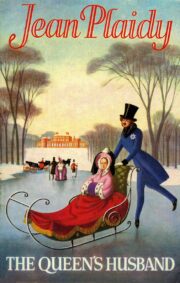

"The Queen’s Husband" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Husband". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Husband" друзьям в соцсетях.