‘His mother was a bad influence on Albert,’ was her verdict. ‘He was growing too much like her. A man’s firm hand is what he needs.’

The grandmothers seemed to be the only women who came into close contact with the boys. Albert screamed less but dissolved into tears at the least provocation. Herr Florschütz was immune from tears. He just allowed Albert to cry; and Ernest said he was a bit of a cry baby.

Albert cried sometimes quietly in his bed when he thought of his mother. Sometimes she had come to tuck them in. Why had she gone away without telling him, without even saying goodbye? Why did his grandmothers look strange when he asked about her? When was she coming back?

He had a little gold pin which she had given him. She had used it once when a button had come off his coat.

‘There is a nice little pin, Alberinchen,’ she had said. ‘It will hold your coat together until the button is sewn on and after that you must keep it and remember always the day I gave it to you.’

So he had and he would take it to bed with him and put it under his pillow; and first thing in the morning he would touch it and remember.

It became the most precious thing he had.

Once Grandmama Saxe-Coburg came into the bedroom and, bending to kiss him, saw that he was crying quietly.

‘My little Alberinchen,’ she said, ‘what is it? Tell Grandmama.’

‘I want my Mama,’ he said.

‘You mustn’t cry,’ she said softly. ‘Only babies cry. You must be brave and strong. Otherwise you won’t be able to marry the little Princess of Kensington.’

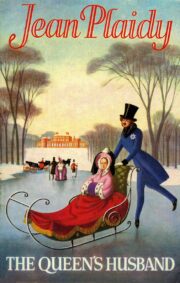

Chapter II

PRINCE ALBERT

Albert had passed his tenth birthday. He no longer screamed to get his own way and had become rather solemn. He was inseparable from his brother Ernest and, although they fought now and then, the bond between them had grown stronger with the years and neither could be really happy out of the company of the other. They were as different in character as they were in appearance. Ernest was tall; Albert shorter; Ernest robust, Albert alarming his grandmothers by his delicate looks. Ernest had bold black eyes and a pale skin; Albert was pink and white with very fair hair and blue eyes. Ernest already had a roving eye and liked to joke with the prettier maids in their father’s castles; Albert had no interest in the women; he enjoyed the company of their tutor and his brother. The only women he was really comfortable with were his two grandmothers.

He had never forgotten his mother. He had a vague idea now of what had happened, for Ernest had discovered and told him.

‘She had a lover,’ Ernest had explained, ‘and so she had to go away. Our father divorced her.’

Ernest gave his version of what this meant and Albert could not forget it. Something terrible and shameful had happened in his family; he knew this was so because of the manner in which no one would explain it to him. Looking back he could see the little Alberinchen who had loved his mother more than he had loved anyone else except himself. She had been so beautiful – more beautiful than anyone else, more loving. No one had conveyed to him in quite the same way how precious he was; no one had made him feel, merely by being close, happy and secure in the same way as she had.

Something had happened when she went away. He was not sure what, but it was for this reason that he had accepted Herr Florschütz so wholeheartedly and was glad the nurses had been dismissed. He did not want to look at women; they reminded him of his mother and something shameful. He loved her as he always had. Whatever she had done, and Ernest implied that it was terrible, he believed that he could never love anyone as he had loved her. He kept the little pin she had given him and he looked upon it as his greatest treasure. But his discomfiture in the company of women persisted because they made him think of vaguely shameful things.

He was happy, though, in the woods and mountains; and his father wished him to excel at all manly sports so he and Ernest spent a great deal of time fencing, riding and hunting. He began to love the beauty of the countryside and became an expert on flora and fauna. There was plenty of opportunity to study these, for their father’s pleasant little castles were situated among the magnificent scenery of forests and mountains. Rosenau, his birthplace, would always be his favourite, but he also loved Kalenberg, Ketschendorf and Reinhardtsbrunnen: and, provided that Ernest was with him, he was happy in any of the family residences. Sometimes they visited one grandmother, sometimes the other. These ladies vied with each other for the affection of the boys; and when Albert could forget his mother, he was happy.

In the early days following her departure she had been constantly in his thoughts, but because of the attitude of those about him he had not spoken of this. Often he complained of pains to the grandmothers and they would hustle him to bed and send for the doctors. He knew that his illnesses terrified them and, as they gave him such importance, he enjoyed them.

‘Oh, Grandmama,’ he would pant. ‘I have such a pain here …’ And it was a great joy to see the alarm leap up into Grandmother’s eyes.

He knew there were conferences about Albert’s health. He was known to be ‘delicate’ – ‘not robust like Ernest’. Ernest was inclined to despise Albert’s delicacy until reproved by his elders for this attitude. Somewhere at the back of Albert’s mind was the thought that if he were ill enough his mother would have to come back to him.

The situation did not persist because at the early age of six he started to keep a diary and, when this proved to be little more than a detailed account of his ailments, shrewd Grandmother Saxe-Coburg felt that they had been unwise to worry so much about his health.

‘The child is obsessed by illness,’ she declared to her son. ‘He appears to take a pride in it. If this goes on when he grows up he will make a point of becoming an invalid.’

It occurred to her then that a good part of Albert’s fragile health might be due to his imagination.

‘Get them out into the fresh air,’ she advised. ‘We’ll let him see that Ernest’s rude health is more admirable than his delicacy. We’ll watch over him as usual but we won’t let him know it.’

The Duke soon began to realise the wisdom of his mother’s council, for although Albert would never be quite the sturdy boy Ernest was, he was fast forgetting about his illnesses and in spite of a weak chest and a tendency to catch cold his health immediately began to improve.

The fresh country air agreed with him and, as the Dowager Duchess said, to see those two boys coming in from the forest after one of their riding jaunts, chattering away about what they called their specimens, one’s fears for their health could be happily forgotten.

Herr Florschütz was good for them too. From the first he had been quite unmoved by Albert’s tears. Once he had startled the little boy during one of the grammar lessons when Albert had been told to parse a sentence and did not know which was the verb – in this case ‘to pinch’ – Herr Florschütz gave young Albert a sharp nip in the arm so that Albert should, he said, know what a verb was. Albert, who had been in tears because he could not find the verb, was startled into silence. Herr Florschütz hinted that he did not think very highly of tears as a means of extricating oneself from a difficult situation, and as Albert had a natural aptitude for learning why not exploit that, and then he would be so proud of his achievement that he would want to crow with pride rather than whine in misery.

So Albert applied himself to learning and Herr Florschütz applauded; so did his father and the grandmothers. ‘You’re the clever one,’ said Ernest. Yes, it was much more pleasant to crow with pride; but only inwardly of course. He was learning very much about life.

He asked Ernest what he wanted to do when he grew up. Ernest thought for a while and said: ‘To govern like our father; to ride, to hunt, to feast, to enjoy life.’

Albert had replied: ‘I want to be a good and useful man.’

Ernest called him a prude which angered Albert, who struck his elder brother. Ernest retaliated and in a short time they were rolling on the grass in a fight.

Herr Florschütz, coming upon them, ordered them to stop and said they should copy out a page of Goethe for misbehaving.

As they did it, Albert apologised. ‘I started it.’

‘Is that what you call being a good and useful man?’ taunted Ernest. ‘Fighting your brother.’

‘I was wicked.’

‘Oh, well,’ laughed Ernest, ‘it’s better than being a prude.’

They laughed together, secure in the knowledge that nothing could change their devotion to each other; and as soon as they had finished their task they were off into the forest to collect wild plants for the collection which they had called the Ernest-Albert museum.

So passed the years until Albert was twelve years old.

The memory of that day in the year 1831 stayed with the Prince throughout his life. It had been an ordinary day. He and Ernest had been at their lessons all through the morning studying mathematics, Latin and philosophy, at which as usual Albert excelled. Ernest was longing for the afternoon when they would get out into the forest. He was anxious to add a special kind of butterfly to the ‘museum’ and hoped that he would be the one to capture it before Albert did. Meanwhile Albert was producing the answers required by their tutor and the lessons were running on the usual smooth lines.

At last Herr Florschütz shut the book before him and glanced at the clock.

‘I should like to hear the song you have composed,’ he said to Albert. ‘I wonder if it is up to the standard of the last.’

‘It’s even better,’ said Ernest, ‘Albert and I sang it last evening.’

‘Then I shall look forward to hearing it this evening.’

Albert hoped the hearing would not be too late; he liked to get to bed early, unlike Ernest, who preferred to sit up half the night. Albert could not keep awake. He would if possible retire after supper on the pretence of reading history, religion or philosophy and Ernest, guessing what was actually happening, would creep up to the room and find him asleep over his books.

Nothing could keep him awake; as soon as supper was over the drowsiness would attack him. What he would have enjoyed would have been to study, to take exercise in the forest, to shoot the birds and collect the butterflies for the museum, to hunt for rare plants and rocks and stones and to study music, compose his pieces, to be tried out with Ernest; and then supper and bed. The trivial social life of the evening tired him; he could be painfully uncomfortable, finding it impossible to hide his fatigue. There had been an occasion when he had actually dozed at table and only Ernest’s constant prodding had kept him from slumping over the table in deep sleep.

Ernest taunted his brother in his good-humoured way; but he would always watch over Albert on special occasions to make sure he did not disgrace himself by falling off his chair and continuing to sleep on the floor – which he had done once when they were alone.

The brothers understood each other. Albert had never had the physical energy of Ernest; Ernest had never had the mental ability of Albert. They were different; they respected the difference; and the bond between them grew closer as the years progressed.

Out into the beautiful forest they rode. They were at Reinhardtsbrunnen, the home of their maternal grandfather. He was dead but his brother Frederick had inherited the title and estates and the boys were always welcome there. How Albert loved the forest, with the sunshine throwing dappled patterns through the leaves of the trees; and riding on and on to where the trees grew more thickly, he recalled the fairy stories their grandmothers had told them and which invariably were set in forests such as this.

‘That was a long time ago,’ he said, speaking his thoughts aloud. Ernest shouted: ‘What?’

Albert told his brother that he was thinking of the stories about the forests where gnomes and trolls, woodcutters and princesses and witches had abounded.

‘You always enjoyed them. They used to tell them to keep you from howling. You were a little howler, Albert. Always in tears. I can remember your screams now. What a pair of lungs you must have had!’

‘I must have been a horrid child.’

‘You were. But one thing about you, you did know how to get your own way. I salute you, Albert. You always will, I’m sure.’

"The Queen’s Husband" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Husband". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Husband" друзьям в соцсетях.