I felt an immense relief sweep over me. I was forgiven. Indeed it seemed as though there was no question or need of forgiveness. If he believed the prophecy and that fate had decided it should come to pass, there was nothing anyone could have done to change it. On the other hand…if it were fanciful nonsense, why bother with it?

So…we would forget it. No harm could come to any of us while we had Henry to guard us.

I gave myself up to the pleasure of being with him again after our long separation.

It was Whitsun Eve when, beside Henry, I rode into Paris. How moving it was to ride through my native city. My mind slipped back, as it must do once again, to those days of poverty in the Hôtel de St.-Paul, and I marveled afresh at the strangeness of fate which had brought me back to ride side by side with the conqueror.

I did wonder what the people thought as they watched me—their own princess—now the wife of the victor.

They lined the streets all the way to the Louvre, shouting their loyal greetings.

My parents were not riding with us. That would have been too humiliating for my father, so he and my mother had gone by a different route to the Hôtel de St.-Paul.

I was richly clad with a crown on my head, to remind these people that I was their future Queen as well as the Queen of England.

It seemed disloyal when their real queen was with my father on the way to the dreary Hôtel de St.-Paul.

We rested that night at the Louvre.

Henry was very understanding and had noticed how quiet I had become.

When we were alone in our apartment, he took my chin in his hand and looked earnestly into my face. “This is a strange day for you, Kate,” he said.

“It is certain to make me feel a little bewildered to be back here in the city of my childhood.”

“All that is behind you,” he insisted. “We are here and this is how it should be. Think of this, Kate. I can do more for France than your father could.”

“If he had never lost his senses …”

“Enough of these ifs. Life is made up of them. Come. We are together. The people of Paris are glad to see peace. You are their Queen…you who were their Princess. They will accept me, Kate, because I am your husband.”

“Let there be peace and I shall be happy,” I said fervently. “Then we can go home to …”

“To our child,” he finished. “How is England for you, Kate, then?”

“Home is where my son is…where you are.”

“Then it is in two places at this time.”

“I would it were in one.”

“It will be so ere long, Kate. I promise you.”

The next day was Whit Sunday, and a great feast was held in the Palace of the Louvre.

“It is an important occasion,” said Henry. “The people will want to see us.”

“They were always allowed into the palace on Whit Sundays…to watch the King at table.”

“Then they shall do so on this day.”

I was carefully dressed and a crown was placed on my head. Henry looked equally splendid. We sat on the dais and about us were all the highest nobles of France and England.

The banquet was served and the people crowded into the palace to watch, just as they had when my parents occupied the places where Henry and I now sat.

I noticed that many eyes were fixed on me.

I wanted to say to them: I do not forget you. I am still French. I married the King of England who is soon to be King of France, but it was all done in the name of peace.

I knew that at the Hôtel de St.-Paul my parents would be sitting in lonely state this Whitsun. How did it feel, I wondered, to know that people had flocked to the Louvre to pay their homage to those who, on the death of my father, would be King and Queen of France? I felt ashamed that I might be seen as a daughter waiting to take the crown from her mother when my husband took that of my father.

I longed for the peace of the nursery, where all such matters seemed of little importance because little Henry had begun to crow with pleasure.

Henry sat beside me, quiet and dignified. Glancing sideways at him, I thought he seemed tired and I knew that, but for his suntanned skin, he would be looking a little pale.

I was longing for the feast to be over. I, too, was tired. I thought, soon we shall depart and the remains of the food will be distributed among the poor who have crowded in here to watch us.

After what seemed a very long period, that time came.

We left and I heard later that the people were sent away without the food which it had been the custom to distribute, that there had been a great deal of complaint and the crowd had at one time threatened to become quite ugly.

“Where is the food?” they had demanded. “Are we to be robbed of our rights as well as our true King and Queen …?”

Joanna Courcy, who had accompanied me to France, said: “I cannot imagine why it was done. I hear it has always been the custom. I heard it was on the King’s orders.”

I spoke to Henry about it later.

“It has always been the custom,” I said. “The people have always had the food that was left over from the banquet. That is why they come.”

“It is not my custom,” replied Henry.

“But…they expect it.”

He shrugged his shoulders. “I did not promise to follow their customs.”

“But the people…seeing us eat all that food when some of them must be in need …”

I should have seen that he was exhausted. But I did wonder why he had given such an order. Surely it could not have mattered to him? Was it just to be different; to show them that in all but name he was their King and the old customs of French kings should be dispensed with?

He did not answer. He sat on the bed, looking more tired than I had ever seen him.

I should have dropped the subject, but something prompted me to say: “It is simple matters such as that which cause revolts.”

“Have done!” he said sharply. “The people will have to grow accustomed to my rule. When I say something is to be…it will be and that is an end of the matter.”

I looked at him in astonishment. It was the first time he had spoken harshly to me.

I was worried about him, and I longed more than ever to be back at Windsor with my beloved child.

Henry slept heavily that night. He had not risen when I awoke. I was accustomed to finding him gone and I sat up in bed and looked down at him anxiously. He looked ill and I was overcome with tenderness, for in his sleep he reminded me of my son. There was a vulnerability about him which I had never noticed before.

“Oh, Henry,” I murmured, “what are you doing? How can you endure these perpetual battles …?”

He opened his eyes and saw me studying him.

“Well,” he said, attempting to smile. “Do you like what you see?”

“No,” I said boldly. “I think you are unwell.”

“Enough,” he said, and I was aware of the look of irritability in his face. “I am as well as ever. It is late, is it not?”

“You have slept longer than usual.”

He leaped out of bed. “Why did you not wake me?”

“I have only just awakened myself.”

“And wasting time contemplating me and coming to the conclusion that my looks do not please you.”

“You need rest,” I said.

“I need rest as much as I need an assassin’s knife. For me, Kate, there is no rest until there is peace throughout this land.”

“And then I doubt not you will have other plans for conquest.”

“No. I plan to go on a crusade.”

I stared at him.

“I’d take you with me,” he added.

I did not answer. I knew that would never come to pass.

That very day there was news. My brother Charles, the Dauphin, was on the march. He was going to attack the enemy, the Duke of Burgundy.

Burgundy was now Henry’s ally, and when he heard the news he said: “I must go to the aid of Burgundy. It would be a disaster if he were defeated by the Dauphin.”

“Need you be involved?” I asked.

He looked at me as though I were foolish.

“But of course I’m involved. The Dauphin had a victory when my brother Clarence was killed at Beaugé. That gave the enemy hope, and hope is something we must not let them regain. You do not understand these matters. I shall have to leave at once.”

“Could you not send your army and remain for a while?”

“Remain here…when my army is on the march! What are you thinking?”

“Just that at this time you seem to be in need of rest.”

“I? In need of rest! When there is an army to lead?”

“So…you will go?”

“Kate, sometimes you ask the most foolish questions.”

“I would you could stay behind.”

He turned from me impatiently. But a few seconds later he turned back and took me into his arms.

“Fret not,” he said. “I will be back with you ere long.”

“I pray that you will,” I said.

I went with him as far as Senlis.

There he decided I might be too close to the fighting. “Better,” he said, “that you go to Vincennes.”

I said: “I shall be close to you here.”

I saw the impatience in his face. “You will go to Vincennes immediately.”

So I left for the castle in the woods of Vincennes and he went on to Senlis.

It was only a few days later when I heard the sounds of shouting below my apartments in the castle. I looked down from my window and I could scarcely believe what I saw. Some men were carrying a litter and in it lay Henry.

I hurried down. He was very pale and half-conscious. It would be useless for him to attempt to hide his condition now.

One of the bearers spoke to me. He was tall and very good-looking and spoke English with an accent I did not recognize.

He said: “The King has been forced to leave the army. He could go no farther.”

“I see. Can he be brought up to the bedchamber?”

“At once, my lady.”

They carried him up. He lay on the bed…breathing deeply.

The tall bearer said to me: “My lady, you should send for a priest.”

I knew then how ill he was.

He was in fact dying. It seemed incredible that one so strong, so seemingly invincible, could be so suddenly struck down.

I said to the bearer: “We will nurse him back to health.”

He looked at me rather sadly and with such pity that I was deeply touched.

It was some hours before I could convince myself that this really was the end.

Henry had suffered from dysentery for some time. It was the soldier’s disease and taken for granted, so was lightly brushed aside. Now he seemed to have some disorder of the chest, for he coughed a great deal and his breathing was difficult.

The physicians shook their heads gravely, implying there was little they could do.

The Duke of Bedford left the army and came to his bedside. I was glad of his presence. He was the one of Henry’s brothers whom I had always trusted most.

“Be of good cheer,” he said to me. “He will recover. He always achieved what to others would seem impossible.”

I tried to smile, but it occurred to me that this time he was fighting a more formidable enemy than the French.

The confessor was with him. Henry managed, between gasps, to ask forgiveness for his sins. What were his sins? Those peccadilloes of his youth? Or the blood which had been shed on the battlefields of France? He did not mention that.

His confessor was reading the seven psalms. He came to the phrase “Build thou the walls of Jerusalem” when Henry feebly lifted a hand as a sign for him to pause.

He said between gasps: “When I had completed my conquests in Europe…it was always my intention…to make a crusade to the Holy Land.”

I wished that these thoughts would not enter my head at inopportune moments, but I could not help wondering whether he thought a crusade to the Holy Land would compensate for the misery and bloodshed he had brought to my country.

The harrowing bedside scene continued and I felt I could endure it no longer.

I whispered to the physician: “He will recover, will he not?”

The man did not speak; he just looked at me as though begging me not to demand a direct answer.

“I would like the truth,” I insisted.

“My lady…it will be a miracle if he lasts for another two hours.”

Henry asked for his brother Bedford, and the Duke, who was already at his bedside, came forward and took Henry’s hand.

“I am here, brother,” he said.

“John…you have been a good brother to me.”

“My lord King, brother…I have always sought to serve you.”

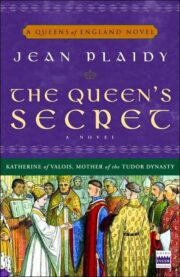

"The Queen’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.