“It was not so,” said Owen. “He cared for you deeply.”

“He cared for his conquests more. James cares nothing for anything but Jane. That is how I would be loved.”

Then he said a strange thing! “My lady, perhaps you are.”

I looked at him in silence. Then suddenly he bowed and, turning, left me alone in that room.

After that I thought a great deal about Owen. It would be foolish of me to pretend I did not know he harbored a special feeling toward me, as I did to him. I was content with my life as it was at this time. I wanted it to go on and on. I wanted Henry to remain a baby while I went on seeing Owen frequently.

It was absurd, of course. Owen was a handsome young man about my own age; he was brave, good, kind, understanding and clever. But what was he? A squire from some wild country beyond the borders. I did not know very much about the geography of my new country, but I had heard that there were certain remote parts which gave trouble from time to time and that they were inhabited by races not entirely English.

I wanted to learn more about the Welsh.

Guillemote, because she had actually come with me from France and was French herself, understood me well and, being inclined to speak more frankly to me than the others, plucked up courage to comment on what was becoming obvious to them all.

“Do you think you see a little too much of your Wardrobe Clerk?” she asked.

“Owen Tudor!” I cried, taken off my guard.

“That was the man I was thinking of, my lady.”

“See too much of him! But there are certain matters which I have to discuss with him.”

“They seem to be very long and animated conversations.”

“I think, Guillemote, that you are …”

“Forgetting my place. Forgetting that I am speaking to the Queen. Oh, I know what you mean. But I do not forget also that I looked after you as a baby. Who was it you came to when you cut your knees…when you saw bogeys in the night? Tell me that. It was Guillemote. You may be a great queen, but you are still my little one…to me. And let me tell you this, there are greater dangers when you grow up, my lady. And when I see you walking into them, I shall say so…and if that means stepping out of place…if it means talking to the Queen as though she is a child…then I will talk.”

I smiled at her lovingly—Guillemote, my comfort in the dark days in that dismal and often frightening Hôtel, Guillemote who had come into my bed to cuddle me and keep me warm, Guillemote who, I think, would have given her life for me.

“I’m sorry, Guillemote,” I said. “I know you love me. I know that everything you do is for my good. You do not have to tell me that, Guillemote.”

“So now I will speak. It is true that you are shut away at Windsor. But people notice. They say how friendly you are becoming with the Clerk of the Wardrobe. Do you need to talk so much of silks and brocades? He is a very handsome young man, and his manner…and yours…is not quite that of a queen and her wardrobe clerk.”

“I like the man, Guillemote.”

“That much we know.”

“I find him interesting to talk to. He comes from a fascinating background. I did not know anything about the Welsh until I came to this country.”

“There are other ways of learning. I think of you as my little one still. You have always been precious to me. If I saw you running into danger, I would be after you. I would take you up in my arms …”

“I know, Guillemote, but I am not a child anymore.”

“No. You are not a little princess. You are on more dangerous ground. You are a queen…and a queen in a strange land.”

“It is my land now, Guillemote. I became the queen of this country because my husband was king and now I am still a queen.”

“That is what I say. So take care.”

“Why should you see danger, Guillemote?”

“Because I know you well. When you talk of that man I hear in your voice and I see in your eyes…what he is becoming to you.”

“I admit, I enjoy talking to him.”

“That is clear to see.”

My lips quivered as she put her arms around me. She rocked me to and fro as she used to do when I was a child.

“I understand…I understand,” she murmured. “But you must take care. A queen could never mate with a wardrobe clerk, and a Welsh one at that.”

“What does his country matter?”

She shrugged her shoulders.

I went on: “I did not know of these other races here. I thought they were all English. We did not hear of the Welsh in France.”

“There is much we did not hear of. And it is not only the Welsh in him. Think of it. He is a soldier from nowhere. What could come of this? Nothing…nothing…but misery. That is why I say, dear Princess, my dear, dear Queen, take care.”

I put my arms about her and clung to her for a few seconds. Then I withdrew myself.

“What are you thinking of, Guillemote? How could you ever think I would have such a thing in mind!”

She looked relieved. “It was silly of me. Of course you would not. It was merely that…oh yes, it was foolish of me.”

“Guillemote,” I said, “we will forget this nonsense.”

I knew the peaceful days must soon come to an end.

It was a year since Henry had sat on my lap and we had ridden through the streets of London. I often smiled to remember how quiet and solemn he had been, listening with what seemed like pleasure to the shouts of the people.

There came a message from the Council. The King’s presence would be needed at the opening of Parliament.

He was now nearly two years old and had grown considerably since he had made his first public appearance. He was not the docile infant he had been.

Preparations to leave for London began.

I did not see Owen Tudor before we left. I had avoided him after my conversation with Guillemote.

Her remarks had made me assess my feelings more honestly. I saw that I had allowed myself to slip into a very pleasant relationship without realizing that it would be noticed and might be misconstrued by those about me.

It had been so comforting to be with him, to discover something of his background and to talk to him about my early life and his. He had listened with great attention and sympathy and made me see those days less grimly than I had before. I would find something to laugh at, though previously I should have thought that impossible.

We were young. Twenty-one or -two is the age for gaiety and romance. Two people as we were, put together, with similar tastes, must be attracted to each other…and such attraction could quickly strengthen into something deeper.

Yes. I was in love with Owen Tudor, if being in love means a lifting of the spirits when a certain person appears, of wanting to be with him above all else, of feeling completely at one with him, wanting to reach out and touch him, to be close to him and never go away.

Yes, that summed up my feelings—but I was the Queen and he was a humble soldier from the remote country of Wales.

Guillemote was right. I should be watchful of myself. More than that…a wise woman would send him away…right away…out of Windsor…out of the household.

Send him away! Give the impression that I no longer wanted him in my household, when he had made Windsor such a happy place for me!

Of one thing I was certain. Wise or not, I was not going to send Owen away.

In the meantime I had to consider the journey to London. I was afraid. They would realize that Henry was growing up and that it was time they took him out of his mother’s care.

He was my child. I had borne him. Why should I allow them to wrest him from me? I wanted to keep him with me. I wanted to keep Owen with me…to go on as we had been.

We left on Saturday, November 13. I remember the day—dark, gloomy, typical November with a mist in the air. I always felt there was something ominous about mists. I remembered the last occasion. The weather had been similar then.

Henry was quite happy. He was with me and was interested in everything he saw.

I think he was forward for his age. He babbled a lot and could say a few words, and one of these was a decisive “no” when something was done which he did not like.

But he enjoyed the journey, sitting on my lap as we rode along.

We spent the first night at Staines, and he awoke next morning in a bad mood. Where were his familiar surroundings? Where was Guillemote?

I said: “We are going to have a great deal of fun. We are going to open Parliament.”

He was dressed with difficulty, protesting all the time, and when he was taken out to the litter, in which we were to make the journey to London, he screamed and kicked out at everyone who approached him, except me. And me he regarded with reproachful eyes.

“No, no, no,” he said emphatically.

He kicked and struggled when it was attempted to lift him into the litter.

We could not very well travel through the villages where the people would come out to see him and discover that their little King was a bawling and protesting child.

There was a hurried conversation. It was decided that it would be better not to leave and that we should, therefore, stay another day in Staines.

One of the guards came to me and said: “My lady, it is the Sabbath Day. We believe it is because of this that the King refuses to travel.”

I stared at him in amazement. Could he really believe that Henry was aware of what day it was?

He said: “They are saying, my lady, that he is going to be a great and pious king and as such he will believe in keeping the Sabbath holy.”

My scowling and red-faced infant looked anything but pious to me; but I was glad they had construed his behavior in this way and thought it better not to raise contradictions.

So that day was spent at Staines. I was dreading the next for fear of more tantrums, but Henry awoke in a sunny mood. He chuckled with glee when he was being prepared, and his mood did not change when it was time for him to get into the litter with me. He held my hand firmly and allowed himself to be placed in it, smiling the while.

His demeanor confirmed the belief that his anger had been because they were trying to make him travel on the Sabbath Day; and thus the rumor of his pious destiny was first founded.

The rest of the journey was uneventful. He was interested in everything. He laughed and I taught him to wave at the people, which naturally delighted them.

We had another stop at Kennington, and it was Wednesday when we rode to Parliament. Henry was dressed in a gown of crimson velvet and wore a cap of the same material. On the cap was set a crown—very small, to fit his little head. He was very interested in this and kept putting up a hand to touch it proudly. They had given him a tiny scepter to hold, which drew his attention from the crown.

The occasion was a great success. He played his part well, showing an interest in the people and now and then saying a word or two in his baby language. He raised his hand in acknowledgment of the cheers and waved to the people.

They adored him.

“God bless our little King!” they shouted; and even his father, returning as the triumphant conqueror, could scarcely have received a more enthusiastic welcome from the citizens of London.

This impeccable behavior continued throughout the ceremony.

He appeared to listen to the speeches with great solemnity, staring at the faces of the speakers and now and then giving a little grunt or crow as though in acquiescence.

He was a great success and I was proud of him, though at the same time very uneasy. They would be more than ever reminded that he was growing up, and that was what I most dreaded.

Soon after the opening of Parliament we left Westminster. I was conducted to Waltham Palace, where I stayed for a few days and nights and from there went to Hertford. It was not Windsor, but it was almost as good, or I found my household assembled there waiting to welcome me. And among them was Owen.

When they all greeted me, he looked at me with such love and longing in his eyes that I could no longer be blind to his feelings for me; and my own response would have told me—if I had not known already—that I returned his love.

We were to spend Christmas at Hertford, which was an indication of what was to come, for this had already been decided for us and was not of my choosing. I knew that those who had chosen would now determine how and where the King should be brought up and were reminding me that they had not forgotten their duty.

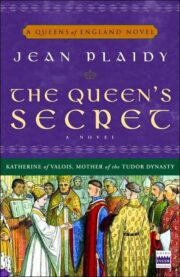

"The Queen’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.